You can’t bury a maniac synthesiser player forever. They may be in a state of hibernation for decades, but when the time is right, they reanimate, more lethal and indestructible than ever. Sem Sinatra interviews Osaka modular synthesiser musician Shinpal.

Shinpal, wildly prolific ambient music and modular synthesiser player was the first modular synth player whose music I connected with immediately, and I was very curious about his working methods and attitudes to music, so I invited him to have a chat with me.

SS: Please tell us a little bit about yourself.

HM: My artist name is Shinpal, my real name is Hiroshi Morita. I’ve released albums under both names. In a nutshell, my music is electronic music. I can’t play acoustic music anymore, I’m no good as that kind of player. I use modular synthesisers and hardware synthesisers. I also use software instruments like those on the iPad and PC. I don’t really like the word genre, but I guess you could say I make ambient music mainly. But also rhythmic house music, deep house.

SS: When did you first start to play music?

HM: I didn’t start playing music as a young child, I was just a boy who loved music. It’s a very common story for a Japanese person of my age, but everything started when I was in high school and I heard Yellow Magic Orchestra for the first time.

When YMO appeared on the scene, I was really shocked, but I loved their music and I wanted to play like YMO. So I started getting interested in synthesisers. Many other children of the same age felt the same.

While I was in junior high school I got a part-time job, saved up my money and bought a cheap synthesiser. From that point, I started to compose music by myself and play it on the synthesiser. That’s how I started playing.

SS: So how old were you when you got your first synthesiser?

HM: Let’s see. I was in the eighth grade, so I think I was 14.

SS: Oh, you started playing it at a very young age, didn’t you?

HM: Yes, I suppose I might have. There’s a place in Osaka called Nipponbashi which I’m sure you know. It’s changed a lot over the years. Now it’s a place for otaku. Decades ago when we were in junior high, it was a real electronics town then. You know home appliances, TVs refrigerators et cetera. There was an interesting shop for maniacs, a shop that had synthesisers and a lot of stuff like that. So I took my money and I went there to buy one. And that’s how it all started.

SS: Was it a normal already made synthesiser, not a kit that you had to put together yourself?

HM: Yes, it was a proper fully made synthesiser from Yamaha. At that time there were only three Japanese synthesiser manufacturers, Yamaha, Rowland and Korg. I bought the cheapest one. The monophonic Korg MS 10. Nowadays, it’s quite a famous machine. Anyway, I bought one of those and then I took it home and plugged it in and made all those bleep and bloop sounds.

SS: Did you start recording it straight away?

HM: Yes, on to cassette tape using a microphone. Then a bit later on, I set up two cassette decks so that I could do ping-pong recording, bouncing tracks from one to the other, gradually building up each song.

SS: With the tape noise getting louder and louder with each bounce?

HM: Yes, exactly. It was so much fun in those days.

SS: So you continued like that, occasionally buying something new and then maybe buying a four track tape recorder?

HM: I just carried on more or less like that. And then when I was in high school, I bought a little polyphonic synthesiser. After that I bought a four-channel Tascam four track tape recorder and started writing songs with it. I was able to make us a reasonable amount of music with it, then I went to university and I was in a band with my college roommates. We did a few gigs and then I graduated and got a job. I didn’t think I’d ever return to it. I didn’t think I’d have the time. I got married and had a child, and only did music as a hobby. I didn’t really have enough time to play properly anymore.

But even then, I still really loved music, and I was listening to music every day and checking out new sounds all the time. It was like that for quite an extended period, but when the kids reach junior high school age, you have a lot of time again. They got to the age where they were doing club activities and that kind of thing so I started to think about doing some music with my synthesiser again, and taking it more seriously. And as I’d been working full time, I had enough money to buy whatever equipment I needed.

SS: How old were you at this time?

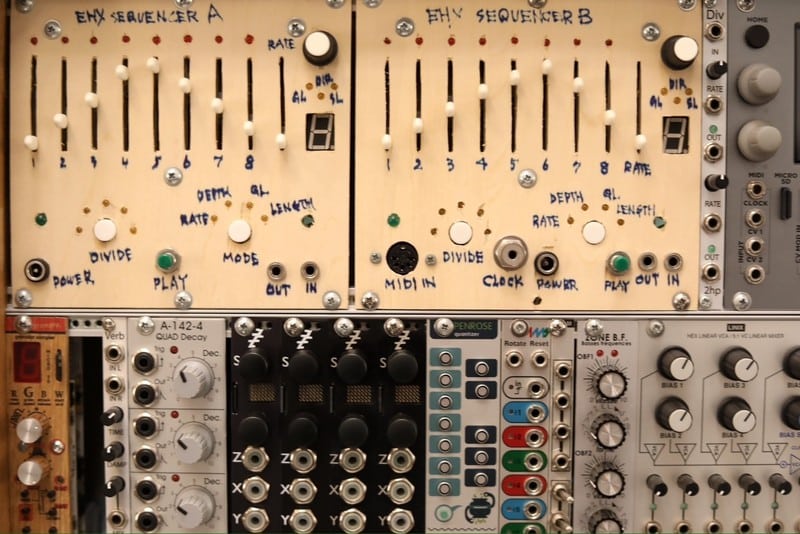

HM: I was about 40. Now I’m over 50. Then about 10 years ago, I started working on a modular synthesiser. Modular synthesisers had started to become very popular and still are. They started overseas at first and then made their way to Japan. In Kansai too, many musicians started playing around with them. I saw many blogs written by those musicians, and I thought the instrument looked really interesting.

Isao Tomita and Keith Emerson

HM: I used to be a fan of Keith Emerson (from the prog band Emerson Lake and Palmer) and the famous Japanese musician Isao Tomita (whose most famous work is an electronic version of the planets by Gustav Holst.). I had always been fascinated by modular synthesisers and prices of that kind of instrument had come down a lot. There was a project called Eurorack. So I thought I’d try a smaller modular synthesiser, bt the time, there were no shops for instruments like that in Japan, so I had to import what I wanted directly from overseas. Japan has been slow to start selling modular synthesizers and most of the manufacturers are still overseas in Europe and America, although there are some shops in Tokyo now. Anyway, I was able to use my credit card to buy what I wanted over the Internet from abroad.

SS: How long ago was this?

HM: It was about 2012. That’s the year I really got into modular synthesizers.

SS: I remember seeing you play at a modular synthesiser event in Shinsaibashi about four or five years ago.

HM: Yes, it was just before the coronavirus time, modular synthesizers were getting really popular and there were a lot of people who had bought them in Kansai and were doing live shows. I wasn’t able to get connected with those people straight away, I was just doing it on my own, but there was a music shop called Shimamura Gakki at Loft in Osaka. One of the shop assistants there was really interested in modular synthesisers. I mentioned that I was working on one and he said, “that sounds interesting”. He eventually became the expert in charge of them at the shop. Some of his customers and acquaintances were semi-professional and some were even professional. We started holding events for them organised by the shop.

SS: Yes, I think that’s where a friend and I saw you playing once.

HM: there are a lot of musicians who are composing at home with this kind of set up. And they started to play live shows and hold events together. It was a very interesting time. This was in around 2017 or 2018. I recorded one of those performances for a Bandcamp release.

SS: You were pretty busy in 2018, weren’t you? I think you released maybe five albums that year, some in Japan and some in other countries.

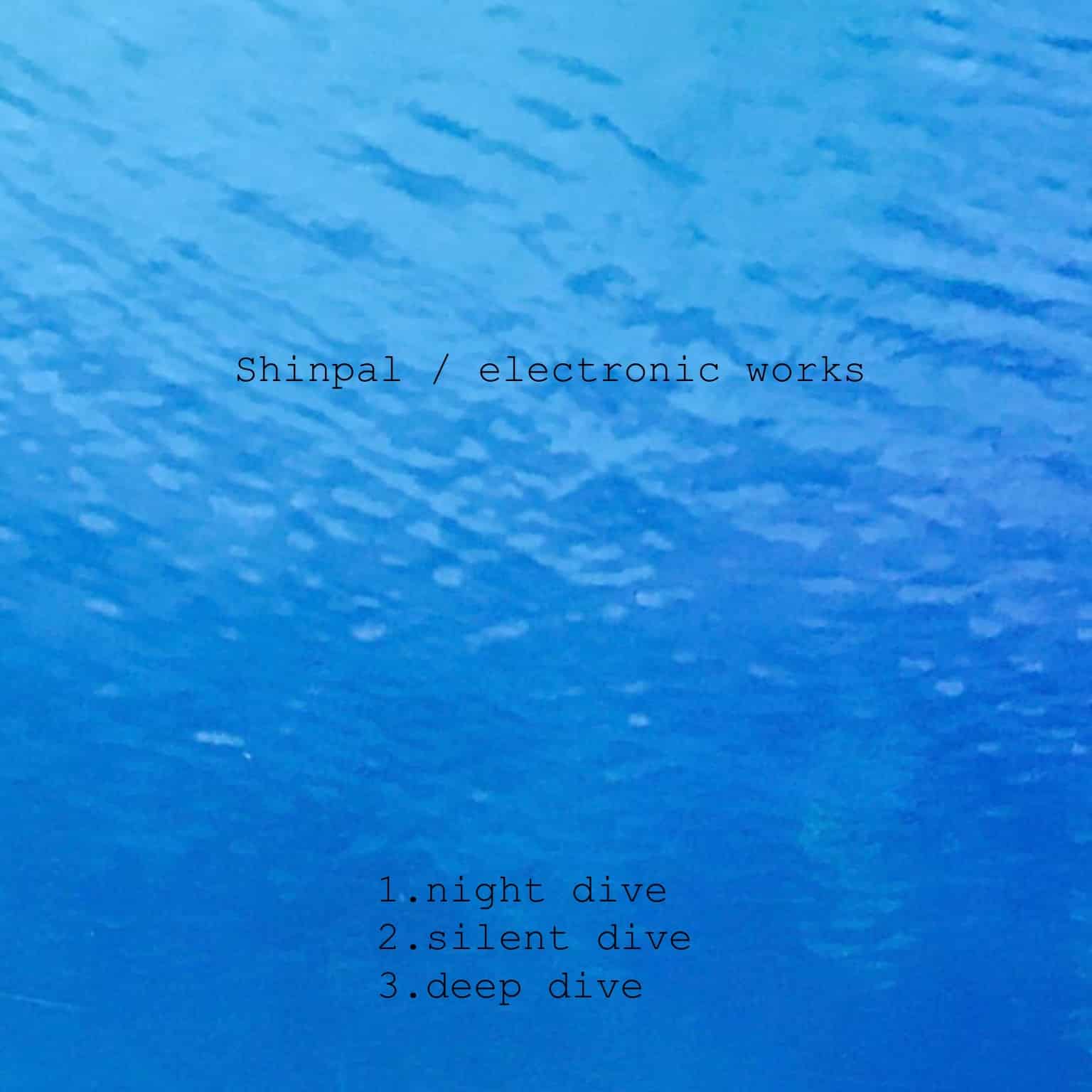

https://gameoflife.bandcamp.com/album/shinpal-electronic-works

HM: That’s right., I knew that Bandcamp was becoming quite popular at the time but I’d never used it myself. I was talking to somebody who was organising event with me and he said it was interesting and I should give it a try. I don’t think ambient music is very commercial, so I didn’t think it would be possible for my music to get a release on a major label. That’s why I decided to do it the DIY way, and set up my Bandcamp page so that I could see how my music would be received.

Shinpal crashes Fat Cat!

Then I started asking ambient labels in other countries if they would be interested in releasing my music. In the past, I used to make a lot of dance music and I wanted to release it on an overseas label. I went to England once and tried to speak to somebody at Fat Cat Records. I didn’t even have an appointment, but I went there and said, “Please listen to this demo CD!”

SS: How did that go? Did anything come with it?

HM: No, nothing happened. I don’t think we had the same musical taste, and the quality of the music wasn’t good enough. I was still working on my sound but it wasn’t really ready. It was hard work and there were many failed attempts, but after trying 30 or 40 times, I found somebody who liked it. Then we were able start to discuss a release.

Theft of music

SS: So what has your experience with overseas labels been like?

HM: Basically, it’s been a good experience very good experience most of the time. But I’ve had a couple of bad experiences including a label who used one of my tracks on compilation without asking my permission. I sent a few tracks to a well-known label and I noticed that a few months later a compilation album came out with one of my tracks on it. They didn’t mention it. They didn’t even tell me about it at all.

SS: That’s unbelievable. They just stole your music basically!

HM: Yes, exactly. Anyway, I edited the old recordings and put them out as an album.

SS: After 2018, 2019 was also quite busy. Then after that, it seems that you slowed down quite a lot. Why was that?

HM: Well, it’s as I was saying earlier. I have children and they were studying for university entrance examinations, and I was trying to help them with their studies. As you know these entrance exams for Japanese universities are very hard so I wanted to to help them. I was just busy with my family and I didn’t have much spare time. And then Covid happened. When I’m at events, I communicate with a lot of people and get really motivated and want to make music again, but when that happened, I stopped going to those event events and lost a lot of my motivation. That was a very important factor.

SS: It’s not always easy to be motivated. Some musicians say if you don’t feel like doing it, you shouldn’t do it.

Mostly you seem to have put out an album a year, but last year you didn’t put out anything. Why was that?

HM: I haven’t been using modular synthesiser so much recently. There are a lot of music composition tools for the iPad, and recently I’ve become really interested in those. So I decided to go off in a slightly different direction and learn how to use those tools to write some new music. I guess you could say that I’m studying. I’m finding it really interesting and enjoyable and that’s what I’ve wanted to do recently.

The owner of the Seagate label has put out some of my music is a very nice guy, and he emails me a lot. In 2020 he didn’t put out anything of mine. Then he mailed me and asked if I wanted to send another recording which he would put it out immediately. I intended to improve the recording before sending it, but in the end I didn’t get round to sending it at all. Somehow the timing didn’t work out.

SS: Well, it’s important to be happy with the work you’ve done before you allow it to be released. Otherwise, you might have regrets about it later.

What does music mean to you and what is its function?

SS: Something else I’d like to ask you: what does music mean to you, and what is its function?

HM: That’s a good question, if a slightly difficult one to answer. First of all, I can honestly say that I love music. Since I was a child, I’ve listened to all kinds of music, basically every day. Even now there’s a day that there’s not a day that goes by when I don’t listen to music. I can’t imagine my life without music.

It is sometimes said that “life is music”, or “music is life”. For me, life is music. I think my life has become like that.

I’m not really sure whether I should tell you this story or not, but at one of the modular synthesiser events I had a really interesting conversation with someone. At those events there are non-professional musicians and professional musicians. I was talking to one of the professional musicians and he said something like: “We pour our lives into music and make our living from it, so we have to work much harder than amateur musicians to deliver our music to the world.” he said it with a great deal of gravitas, feeling that he had to make better music than non-professionals can make. When I first heard that I thought: “That’s really wonderful. He’s really taking it seriously.” But then I thought: “Hey, us non-professional musicians are also working hard. We’re holding down a day job but we’re just as passionate about music, and that passion is something that can never be extinguished. We’re making music every day, as well as living the other parts of our lives.” Without music, I wouldn’t be able to live my life so I don’t feel out done by that kind of professional musician. It’s not that I’m not passionate about music. On the contrary, even though I’m a non-professional musician, I have a huge amount of passion for creating music and I won’t be outdone by this measely difference. I’m not usually conscious of this feeling, but you know, music is really part of the soul.

SS: There are a lot of professional musicians, some of whom make good music and some of whom make bad music. There are also a lot of non-professional musicians, some of whom also make good music and some bad, so the difference between the two of them to me is nonsensical. Whether it is a person’s job or not, to me, has nothing to do with whether their music is good or not. It’s only the finished result that matters. I also hate the word “amateur” in this context. It implies that the music created is inferior to that produced by a so-called professional.

HM: I don’t really care about musicians themselves, only about the music they produce, and perhaps any interesting ideas they might have. Maybe it’s because musicians are generally quite selfish with their time, that they are able to create music.

SS: So … back to music meaning and function… (laughs)

https://mimirecords.bandcamp.com/album/texture

HM: Well as I said, I love music very much. But actually, it’s more that I was saved by music. That’s true really true. When I was in high school, I was very introverted, very shy. I wasn’t really able to express my opinion at all. I didn’t know how to do it. But I found that listening to music at home gave me the courage to go to school the next day and keep trying. So music has always helped me get along.

Shinpal’s Musical Theories

SS: do you have any musical theories? I mean, while you’re making music, have you formed any theories or ideas about music?

HM: I can really only talk about the music that I do, which is ambient music. There are many different kinds of ambient music. When you first hear it, it always seems to be quiet or drone or noise or field recording, sometimes with sometimes without. There was a time when I was very conscious of what ambient music it was and how to make it. When I first started using modular synthesis as I was trying to make dance music with a strong beat, but I couldn’t do it. It was impossible to synchronise all the rhythms together. With all the modules that are available now I could do it, but but back then it was much more primitive: Oscillators, filters, and a simple sequence was all I had to try to build my sound. So with the sound of bloops and beeps, I wondered what kind of music I could make. So I ended up making something more broadly electronic. I thought it would be more interesting and more fun to aim for something slightly different. So I decided to make the sounds I wanted to make, and then combine them without synchronising the timing.

SS: Oh, so you don’t synchronise them?

HM: No, it’s completely un synchronised. I played each part separately then I mix them together, however I’m feeling at the time. Techno and other dance music is extremely demanding in that sense, but I don’t care about the timing at all, only about feeling. It’s all about the feeling.

For instance, in the space around us right now, there are all kinds of sounds going on, aren’t there? The sound of the waitresses rattling plates and cups, people talking, the sound of us drinking our beer. It’s all very random. And even though it’s irregular it’s very pleasant of the year and as the sound of daily life, it’s quite acceptable. And if you take that kind of thinking a bit further, for instance, when we go to a river or the sea, we we hear the sound of the water, don’t we? As you’re looking at the sea, your hearing that shaa shaa sound. There’s no monotony or repetition if you listen very carefully there’s a great deal of variation within it. It’s extremely complex. With ambient music, you don’t have to change the melody dramatically. It can be a drone or a noise, it doesn’t matter, and it can change gradually over time. And by mixing it with your own sensibility and feelings, it can become something which relaxes the listener. If I play music that’s a little weirder, I believe I can change people’s feelings. That’s what I’m basing my music on now. It’s not really a musical theory, but I’m learning from sounds that exist naturally, and trying to reproduce them electronically.

I’m very fond of the music of Christian Fennes who uses noise and drones a lot. But in the middle of his pieces, he often throws in some guitar which is very melodious. I find that very emotional and moving. I’m trying to do the same kind of thing with modular synthesisers and hardware synthesis.

SS: So that’s why you’re also learning new ways of composing with the iPad?

HM: yes I want to see what it’s possible for me to do in that realm. And I want to try adding more musical elements to make it more uplifting for listeners, to try and raise the human spirit.

SS: It sounds as if your new music is going in a slightly different direction.

HM: Yes I think so.

SS: I find the music that you made with Antonella Eye Polizzi very interesting. Can you tell us a little bit about how that came about?

HM: I don’t remember what year it was, but I was making albums on foreign labels, and I got an email from Antonella completely out of the blue, a poet involved in music and making films projects in France. She said my name is Antonella and I do poetry reading and I’d like to collaborate. with you. I make music with my voice, and I’ll send it to you and I don’t care how you remix it.

SS: So she sent you a recording of her voice and you just got on with making the piece?

HM: yes, after I received the recording, the poetry reading, of about four or five minutes in French, I was wondering what to do with it. I tried juxtaposing noise and drones with it but it wasn’t very interesting. So I decided to cut up the poetry reading into pieces, and put it into a modular synth sampler. Modular synths are very good at playing stuff back at random, so I did that and then added some noise to it. Actually, it was quite well received.

https://antonellaeyeaynilporcelluzzi.bandcamp.com/album/souls

SS: it’s quite different. It’s completely different to the music you normally make, but I think it’s really really good, and I guess that’s what happens when you collaborate with someone successfully. Have you done any other collaborations?

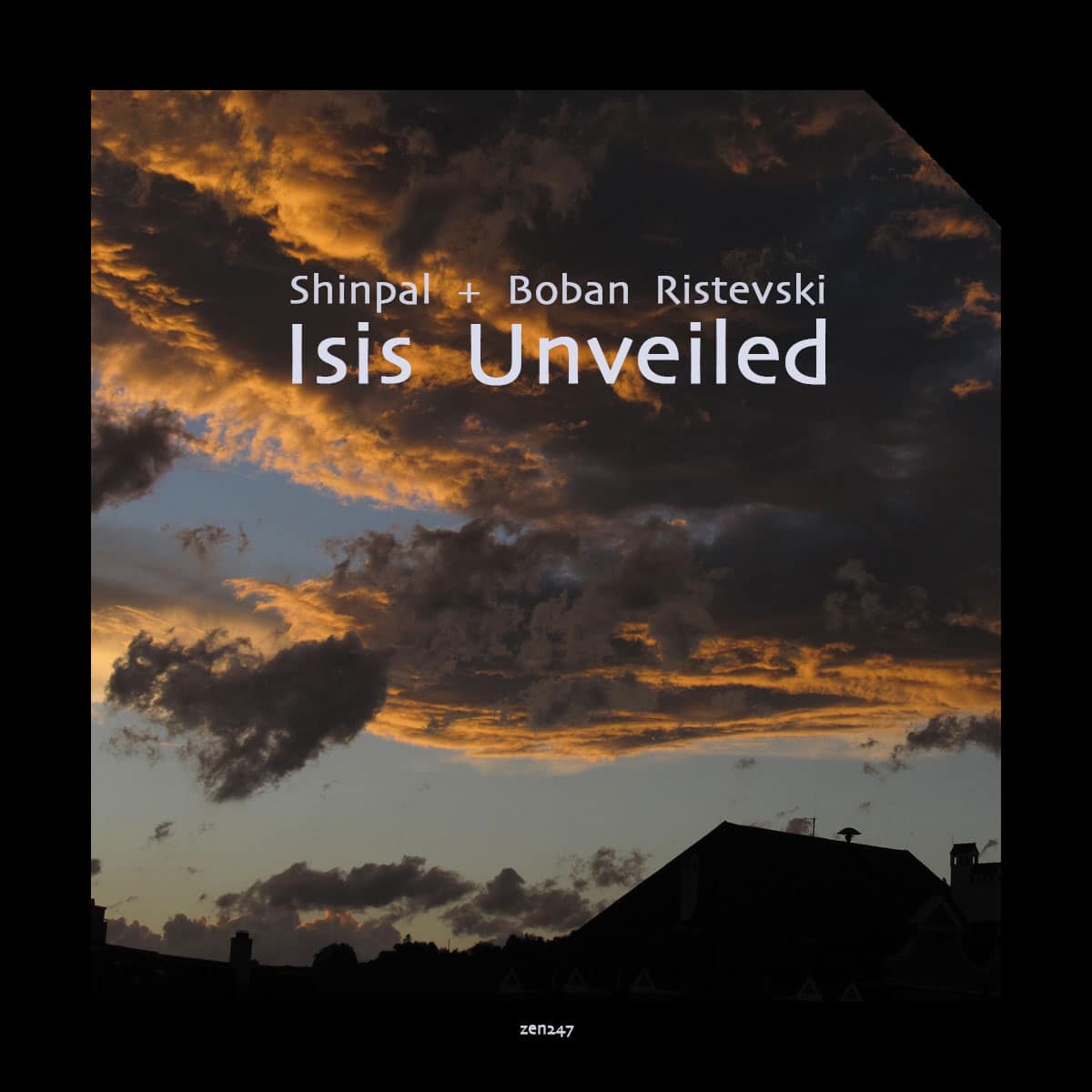

HM: I did I did a collaboration with a musician from North Macedonia called Boban Ristevski which came out in 2022. He’s a noise artist and he asked me if I’d like to collaborate with him, so we made an album together. Usually his music is mostly field recordings.

https://www.zenapolae.com/zen247

SS: I don’t know very much about his solo music, but when you listen to the album that you made together, it’s hard to tell who did what. But that doesn’t really matter at all. The most important thing is that it’s interesting, and personally, I think the collaboration was a big success. I really like that album a lot.

Do you like doing collaborations?

HM: I used to think that doing collaborations was just okay, but for the last couple of years I’ve been doing some shows with a musician in Nara, and since starting to do that, I’ve began to think that it’s a lot more interesting. I’m open to doing collaborations with electronic artists.

For me, doing collaborations with acoustic artists doesn’t seem to work very well. I’ve tried to do that in the past at live events, but it never seems to gel well. I always feel a bit sorry when it doesn’t work out well. If you can bring out the best in each other then it’s fun, but if it doesn’t go well, I feel a bit bad. But I’ve done other kinds of collaborations, for example, with a DJ where we both set up our own equipment and synced our equipment up together and played whatever we wanted. That particular set up worked very well. He played the rhythms and I used my modular synth and played bass sounds over the top of it.

SS: That sounds very interesting. It seems like the most enjoyable thing that can happen in that kind of situation is that although you don’t have control over what is going on exactly, sometimes something really amazing will happen by accident.

HM: Yes, when that happens, it’s very enjoyable.

SS: When you’re making music on your own, do you still get those nice surprises?

HM: Yes, sometimes, completely by chance.

New Releases in 2025

SS: Are you thinking of creating and releasing something this year?

HM: I’ve got a lot of ambient works in the pipeline. And I’m also working on some new deep house stuff.

SS: You haven’t released any of that house stuff yet have you?

HM: No, not yet, but when it’s ready, I’ll release of it via Bandcamp, and I’ll release it under a different name to Shinpal.

SS: I look forward to hearing it. By the way, I noticed that the music that you released under the name Shinpal doesn’t have very much in the way of beats behind it.

HM: That’s right, although I’ve done music with a much stronger rhythmic sense to it, and I’ll be going back to that more rhythmical side soon.

SS: one more thing, you put out a recent release under your own name, an album titled Abstract Poetry. Why did you release that one under your real name rather than the Shinpal name?

https://atlantearecords.bandcamp.com/album/abstract-poetry

HM: That album was made using various pieces of software for the iPad, rather than modular sense, so I decided I wanted to keep it separate. At first I suggested a different name but the guy from Atlantea records convinced me to use my real name, because he likes it. I thought, if they think it’s okay, then I’m fine with it too.

I remember from the early days of dance music that a lot of musicians wanted to be judged only by their music, not by their personality. And they mostly didn’t show their photographs or use their real names. I love those kind of UK techno and also artists like Black Dog who, at the beginning only made 12 inch singles. I really admire all of that stuff.

It’s an ideal for me. I don’t want my photo to appear on my releases, but I want my music on the radio and so on, so that people can listen to it when they’re working or doing something else. If they say it’s good music, then that’s enough for me, the music is the most important thing. Other than that, all the other stuff is really not important.

With YouTube and Bandcamp, musicians can do everything for themselves now, whether they are full-time professional musicians or non-professionals. Everyone can work as hard as they like on the music, and then put it out very easily.

Shinpal official website: https://shinpal.bandcamp.com/