Popular ideas about the culture of Osaka often include food such as takoyaki and okonomiyaki, major comedy acts, and sport teams like the Hanshin Tigers. While these are all very much a part of the local culture, this paints only a limited picture. As a vital location in early Japanese civilisation, Osaka has been settled for millennia, and as such, its cultural influence can be seen through the ages. This essay on Osaka’s cultural history will first set the scene by examining the relationship between the old Japanese language and the modern dialect of the area, before going on to look at Osaka’s place in the arts of ancient Japan. Next, the focus will move to the mediaeval and early modern periods, when Osaka was a major mercantile centre and various art forms including kabuki and tea ceremony flourished. Moving on to modern times, some of the popular associations with Osaka – food, comedy and others – will be discussed, together with the significance of Osaka in other areas of arts and culture. Osaka history

Table of Contents

Language of Osaka

One of the most famous aspects of Osaka culture for people in other parts of Japan is the regional dialect. In modern Japan, the standard language (hyojungo or kyotsugo) is taught consistently in schools all over the country, although local dialects – or blends of regional speech with the national language – are often spoken in different areas. Regional dialects have existed in Japan since ancient times, but such records are limited, as most early written Japanese was based on the language of Japan’s political centre: Nara and then Kyoto. In any case, dialects developed over time, and during the early modern period in particular, the differences between them grew starker.[1] This was due largely to the restrictions on movement between regions under the feudal system, causing isolation of the different linguistic varieties. As a result, some dialects may have been mutually unintelligible, particularly if the speakers were from distant parts of Japan. This is reflected today in dialects such as those of Kagoshima and Aomori, at opposite ends of the country, which are both notoriously difficult for outsiders to understand.[2] Osaka-ben, the dialect of Osaka, is an example of the Kansai dialects also spoken in Kyoto, Kobe, Nara and other surrounding areas, and is perhaps the best-known regional variety of Japanese.

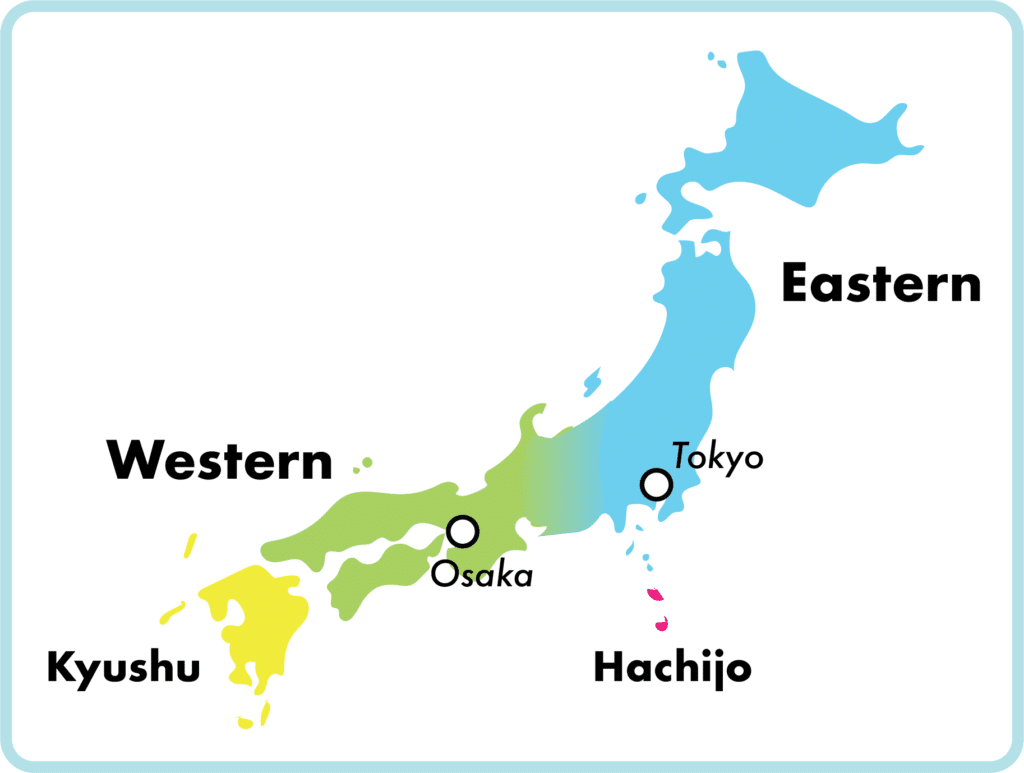

Usually, Japanese dialects are broadly divided into two main branches: Eastern and Western.[3] Most areas to the east of Gifu and Aichi Prefectures follow Eastern patterns, and those to the west follow Western patterns, with areas in the middle exhibiting features of both, and a few areas such as Kyushu and Hachijo Island differing significantly from both. One of the most notable differences between Eastern and Western Japanese is the copula, or the word used for “to be” in the sense of describing something (for example, “Sam is five years old”, but not “I think, therefore I am”). In Eastern Japanese dialects, including Standard Japanese, this word is da, while most Western Japanese dialects use ya or ja. In Osaka-ben and other Kansai dialects, ya is most common.[4] There are also many other differences in vocabulary between Osaka-ben and Standard Japanese. Some of the most well-known of these are the use of honma ni rather than the standard hontou ni to mean “really”, and ooki ni as an alternative to arigatou for “thank you”. Due to the widespread popularity of Osaka comedy and the reputation that people from Osaka have for speaking their local dialect even in other parts of the country, there are also a variety of other Osaka-ben words and phrases that are popularly known throughout Japan.

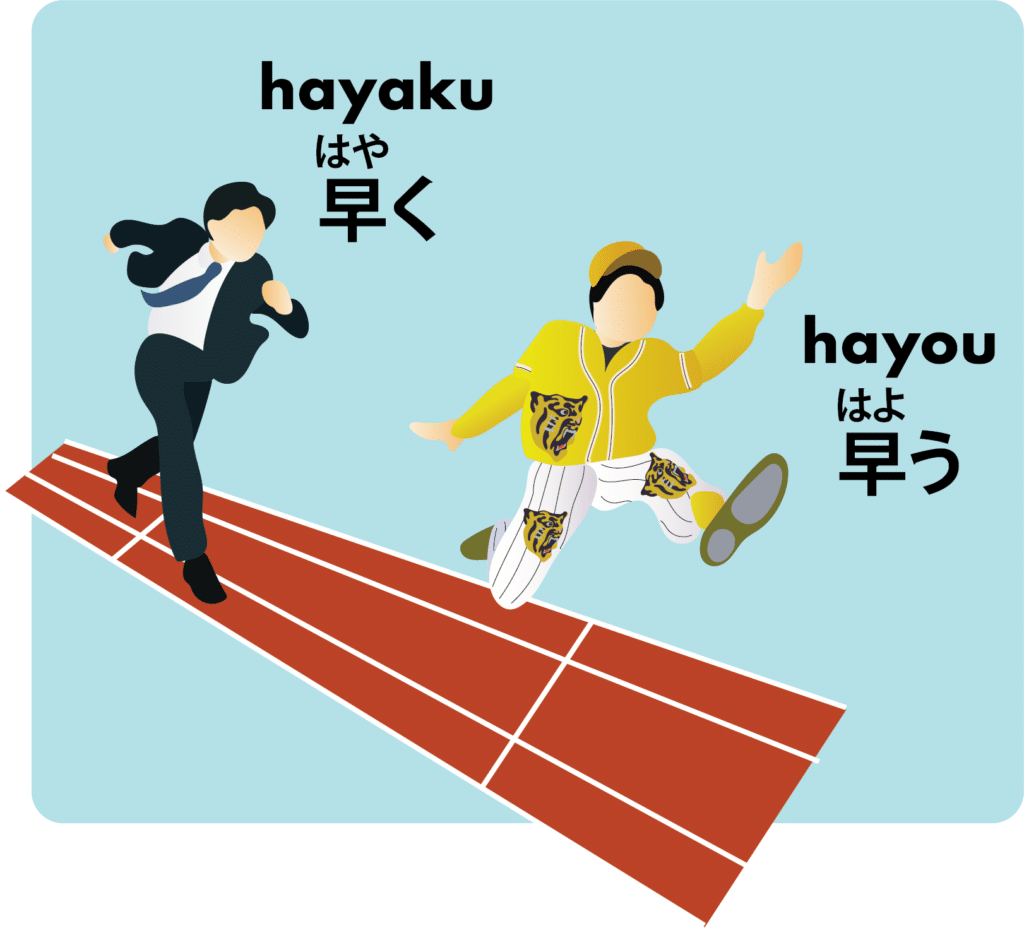

In addition to the use of a different copula, the grammar of Osaka-ben differs from Standard Japanese in other significant ways, which can also be seen in older forms of the Japanese language. Prior to the establishment of Tokyo as the capital city in the 19th century, Japan’s capital was in Kyoto, and though variations already existed all around the country, Kansai dialects were the de facto standard for hundreds of years. However, the change in capital and a desire to encourage unity among the population resulted in a new, officially promulgated standard language based on the speech of Tokyo. Other modern-day language reforms include new orthographic standards, designed to limit the number of kanji (Chinese logographic characters) required for literacy, and to simplify spellings so that they reflect modern pronunciation.[5] New learners of Japanese may now be confused to encounter strange spellings in old writing, where characters for the sounds kefu instead represent kyou, and what looks like afugi should be pronounced as ougi.[6] These odd ways of writing words reflect historical spellings, based on how the words were once pronounced, but the spellings and true pronunciation gradually became more different over time, in much the same way that the spelling of a word like “knight” in English no longer represents the way it is said. As the above examples demonstrate, syllables ending with u came to be pronounced as long o sounds, a pattern that also applies to the conjugation of verbs and adjectives, and can be seen both in historical Japanese and in modern-day Kansai dialects. Just as the classical verb written as tamafu is pronounced as tamou, speakers of Kansai dialects today may render the past form of kau (“to buy”) as kouta instead of standard Japanese katta, and the adjective hayai (“quick” or “early”) becomes the adverb hayou in Kansai, rather than hayaku as in textbooks.[7]

Furthermore, these features are not exclusive to Kansai dialects and older forms of Japanese; they can be seen in Standard Japanese too. There are many polite expressions which demonstrate the old conjugation styles that remain in Osaka-ben and the other Kansai dialects. Some claim that the dialect of Edo – as Tokyo was known before it became the capital – did not feature honorific language whatsoever, but whether or not this is accurate, it is easy to recognise aspects of the speech of the old centre of power in modern polite speech.[8] For example, the common phrase ohayou gozaimasu, meaning “good morning” is based around the adjective hayai mentioned above. Note that even in the standard language, this would never be “ohayaku gozaimasu”. The same pattern is seen in other expressions such as omedetou gozaimasu (“congratulations”, from the adjective medetai meaning “auspicious”) and arigatou gozaimasu (“thank you”, from the adjective arigatai meaning “grateful”). The lingering influence of Kansai grammar patterns can also be seen in negative verb forms in polite speech: rather than the nai ending common in Standard Japanese, polite language will use sen, closely resembling the typical negative conjugation used in Kansai dialects.[9] This pattern is used extremely frequently, for example in an expression that many new learners will be familiar with: wakarimasen (“I don’t understand).

Today, Osaka-ben is closely tied to perceptions of the people who speak it. Many associate the dialect with the society and culture of Osaka, including ideas of warmth and humour, but also crudeness and even threat. Indeed, while an Osaka-ben speaker in a film may be a comic character, it is also not uncommon for them to be a gangster.[10] However, this is mainly a matter of modern popular attitudes, often based on media depictions. As demonstrated above, Osaka’s dialect is also a connection to its cultural history, and its similarities to older forms of Japanese as well as modern polite speech in the standard language serve as a reminder that the region was for hundreds of years the centre of Japanese culture.

Osaka and the Classics

The 6th and 7th centuries CE were a crucial time in the development of Japanese civilisation. During this time, political power was consolidated by a growing imperial court, and the capital was in modern-day Nara – though it moved several times, including to places which are now a part of Osaka.[11] It was also during this time that the Buddhist religion took root in the country. This had a major impact on art in Japan, particularly between that time and the 13th century.[12] Notably, this included a vast array of images of Buddhist deities, such as statues and carvings. One deity that has been particularly popular in Japanese history is Kannon, a bodhisattva associated with mercy and compassion. Kannon is worshipped all over Japan, and their many forms have been portrayed in statues since the early days of Japanese Buddhism.[13] Some of the earliest temples in Japan can be found in Osaka, including Shitennoji, the first to be officially commissioned, and Abiko Kannonji, which is said to be the first temple devoted to Kannon.[14] First founded in 546 CE, Abiko Kannonji is also claimed to have received the very first Kannon statue in Japan, which was brought as a gift from the kingdom of Paekche in modern-day Korea.[15] Another sign of Kannon’s early popularity is the development of a major pilgrimage route, taking pilgrims to thirty-three sites in the Kansai area where statues are on display.[16] Among these, four are in what is now Osaka Prefecture, including Fujiidera, home to the oldest existing example of a Thousand-Armed Kannon figure (senjukannon).[17] The many arms on this variety of Kannon each have eyes on the palm, enabling Kannon to see and aid all those in need. Fujiidera’s wooden lacquerware statue is also remarkable for actually having more than one thousand arms, as despite the name, most statues of this type have far fewer. This statue is designated by the Japanese government as a National Treasure, as is an Eleven-Faced Kannon at nearby Domyoji.[18]

Source: Serai.jp https://serai.jp/tour/246361

Other than Buddhist artworks, this period in history is also known for the development of literature in Japan. Writing was imported from China and adapted to the Japanese language, and literary works began to appear, with the Heian Period between the late 8th and 12th centuries being particularly renowned for its classical culture. The beginning of the Heian Period saw the capital move to Kyoto, and so the Osaka area became further removed from the centre of power, but it continues to appear as a location in works written before, during and after the Heian Period. For example, Naniwa-zu, the name of a port town which was a predecessor of modern Osaka City, is mentioned frequently in classical poetry. It appears in the preface of the early poetry anthology Kokin Wakashu, in a short poem traditionally attributed to Wani, a semi-mythical figure described in early Japanese historical writing as having come from Paekche bearing classical Chinese texts.[19] Other poetic references include three separate mentions of Naniwa in the Hyakunin Isshu.[20] This poetry anthology collects 100 poems, each by a different author, and has become famous as the basis for the traditional card game uta-garuta. The allusions in the Hyakunin Isshu display an aesthetic appreciation for Naniwa, especially the reeds in the bay.[21]

Another recurring location in classical literature is Sumiyoshi, known for Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine, in southern Osaka City. It is the main setting of The Tale of Sumiyoshi (Sumiyoshi Monogatari), a Cinderella-esque story about a girl running from her stepmother and finding love.[22] This story and others like it would go on to inspire Murasaki Shikubu, the author of The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari). One of the most celebrated pieces of Japanese literature, The Tale of Genji is a lengthy work depicting the lifestyles of the nobility in the capital during the Heian Period. Sumiyoshi also makes appearances in The Tale of Genji itself, as the shrine had become well-established by that point as a destination for pilgrims.[23] Both The Tale of Sumiyoshi and The Tale of Genji went on to becomes the subjects of celebrated picture scrolls illustrating the stories.[24]

Finally, another famous work in which locations in Osaka notably appear is The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari). It is an epic of unknown authorship, written after the end of the Heian Period when Japan was in a more turbulent state, and it was originally recited with musical accompaniment.[25] In its retelling of the events of the 12th-century Genpei War between the Taira and Minamoto clans, several familiar locations can be seen. The figures portrayed move between Kyoto, Shikoku, Kyushu and Kanto (around modern-day Tokyo), and in the middle of this is Settsu Province, an area comprising what is now northern Osaka and southern Hyogo Prefecture. Familiar locations including Naniwa and Sumiyoshi appear in the story, as well as others, such as Fukushima and Watanabe-no-tsu, settlements close to where the Umeda area is today. One notable episode takes place at Daimotsu Bay, close to Osaka in modern-day Amagasaki City. At this point in the tale, a loyal friend of one of the Minamoto warriors bravely prays to settle a storm; this scene was later depicted in the famous woodblock print Moon Above the Sea at Daimotsu Bay.[26]

Source: Ronin Gallery https://www.roningallery.com/education/a-closer-look-moon-above-the-sea-at-daimotsu-bay/

Although Osaka was important during the introduction of Buddhism, it then had limited influence for several centuries, as the capital moved to Kyoto and later the political situation became more unstable. As a result, Osaka’s significance in literature was mainly as a location, rather than as the site of production. However, this would soon change, as Japan underwent social and political change and entered the Edo Period.

Edo Period Culture

The Edo Period began at the beginning of the 17th century, after the efforts of samurai lords Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu brought an end to many years of civil war.[27] The country was largely at peace during this time, and under the newly developed class system, local lords called daimyo ruled over their respective domains. During the Edo Period, the city of Osaka developed from various towns and villages in the area and grew as a centre for commerce. In particular, the merchant and artisan classes amassed wealth and so, despite being ostensibly low in the social hierarchy, they became economically dominant, with Osaka being a notable example of this nationwide trend.[28] This section will examine many of the art forms that grew during the Edo Period and the significance of Osaka in their development, looking for example at theatre, poetry and visual arts.

Kabuki is perhaps the best-known form of traditional Japanese theatre. It is recognisable for its all-male cast, where actors wear elaborate make-up and perform in a highly stylised manner. It originated in the late 16th century in Kyoto, inspired by several earlier dramatic forms such as noh and kyogen.[29] Initially, kabuki was performed primarily by women and enjoyed by people of the lower classes, and it soon became associated with immorality and was strictly prohibited. After some early difficulties, it eventually came to resemble the form that is recognised today, and it gained great popularity in the developing city of Edo, where a particularly exaggerated acting style known as aragoto took hold.[30] Meanwhile, in the Kamigata region (Kansai, especially Kyoto and Osaka, usually mentioned in terms of Edo Period arts), a more delicate style called wagoto emerged.[31] Though kabuki is more often associated with Edo – now Tokyo – it was also popular in Kamigata, especially among the newly wealthy merchant class. There are still major kabuki theatres in the area, such as Shochikuza near Dotonbori, where visitors can experience kabuki performances today.[32] Famous kabuki actors take on stage names that pass down through generations of a single family, preserving the tradition; the few remaining actors of Kamigata kabuki generally live and perform in Osaka, including Sakata Tojuro IV and his sons.[33]

While the Kamigata tradition was an important part of kabuki’s history, Osaka’s greatest contribution to the form comes from a different source, via one of the other dramatic forms that influenced its development: bunraku puppet theatre. Bunraku, or ningyo joruri as it was originally known, took on a recognisable form in the late 17th century, building on existing traditions that incorporated puppetry and music.[34] In bunraku, elaborate puppets are manipulated by groups of three, carefully imitating human motions while music is played. Arguably the most important early development in the art form was the collaboration of playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon and chanter Takemoto Gidayu, who opened the Takemotoza theatre in the Dotonbori area in 1684.[35] The name gidayu came to refer to the music used in bunraku performances, in which the performer plays the shamisen while also voicing the characters on stage and providing narration.[36] Chikamatsu is remembered perhaps even more fondly, as Japan’s “Shakespeare”.[37] He wrote dozens of famous bunraku plays, including The Battles of Coxinga (Koksen’ya Kassen) and The Love Suicides at Sonezaki (Sonezaki Shinju). In the latter, a young merchant meets his lover on the grounds of Ikutama Shrine and reveals to her the arrangement of a marriage that is socially difficult for him to refuse; he is soon humiliated, leading to the couple’s joint suicide, a recurring subject in Chikamatsu’s plays.[38] Tsuyu no Tenjinja, near Umeda Station in Osaka, claims to be the location of their deaths in the story that inspired the play, and the shrine is also known as Ohatsu Tenjin, after the woman in the tale.[39] Chikamatsu wrote several plays for kabuki, especially for the actor Sakata Tojuro I – the first in the dynasty that Sakata Tojuro IV later revived – and apart from these, the majority of his bunraku works also received kabuki adaptations.[40] Namiki Sosuke is another famous bunraku and kabuki playwright from Osaka: he wrote some of kabuki’s most celebrated plays, including Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees (Yoshitsune Senbon-zakura), based on characters from The Tale of the Heike.[41] Chikamatsu’s and Namiki’s contributions are a major part of what makes Osaka important to Japanese theatre in general and bunraku especially, with the form’s current name being derived from the 18th-century Bunrakuza theatre which operated in Osaka until the Second World War.[42] Despite several cycles of rise and fall in popularity, bunraku continues to be recognised as an important art form in Japan, and characteristic of culture in the Osaka area.

Source: Japan Arts Council https://www.ntj.jac.go.jp/english/schedule/national-bunraku-theatre/2018/discover_bunraku_2018.html

Another traditional narrative art form in Japan is rakugo, in which a solo performer tells often humorous stories, performing the roles of several characters by varying their tone of voice and using a folding fan as a prop.[43] In much the same way as kabuki, rakugo is typically associated with the culture of old Edo, but there is also a distinct Kamigata tradition, in which Osaka is central. The different traditions developed separately, with Kamigata rakugo being influenced by earlier storytelling forms performed outdoors; this may have contributed to the tendency for being louder and more energetic than Edo counterparts.[44] Other distinguishing features of the Kamigata style reflect some of the social differences between Osaka and Edo. Rakugo stories in Osaka are more likely to focus on merchant characters than samurai or artisans, and due to being far away from the centre of government, characters of different social classes are more likely to be portrayed as roughly equal. Kamigata rakugo also has a reputation for being more realistic, with characters’ actions being acted out in greater detail, and specific locations being listed by the narrator, for example in The Akashi Courier (Akashi-bikyaku), where an Osaka merchant passes by many named sights while travelling on foot to Akashi in modern Hyogo Prefecture.[45] Some practical differences compared with the Edo tradition include the use of a small table called a kendai and small clappers called kobyoshi in addition to the folding fan and hand towel used in other rakugo, and the incorporation of music. Some of these additional features are inspired by kabuki, bunraku and other musical entertainment popular in Osaka. Altogether, these elements create a significant contrast with the more restrained style considered tasteful in Tokyo. Though performing in a fixed location has historically been less important in Kamigata rakugo, efforts to preserve the distinctive traditions resulted in the opening of Tenma Tenjin Hanjo Tei, a theatre next to Osaka Tenmangu shrine, in 2006.[46] A museum devoted to Kamigata rakugo can also be found in Ikeda City in northern Osaka Prefecture.[47]

While there is certainly a literary component to theatrical forms and rakugo, they are fundamentally performative. The most recognisable medium of literature in the Edo Period is poetry, which famously includes haiku and related forms. This is another instance where the best-known individual internationally is associated mainly with Edo, namely Matsuo Basho, especially renowned for the travel accounts he embellished with poetry.[48] However, there were of course other poets of renown all around the country. Ueshima Onitsura was a contemporary of Basho, hailing from Itami in what is now Hyogo Prefecture.[49] Spending his adult years mostly in Osaka, he is often known as a follower of the Danrin school of poetry, which advocated for the use of everyday language and humour.[50] Basho, too, was associated with the Danrin school for a time, before moving on to develop his own style.[51] Another contemporary – and disciple of the Danrin school – was Ihara Saikaku, a prolific poet of Osaka.[52] Ihara became known particularly for setting strange records in writing poems as fast as possible, but the works for which he is now most famous came later. Beginning with 1682’s Life of an Amorous Man (Koshoku Ichidai Otoko), Ihara pioneered ukiyo-zoshi – “books of the floating world” – a popular genre of fiction in the Kamigata region focusing on the lives of the lower classes.[53] These often erotic works were not held in high regard during his lifetime, but were widely read, and ended up being influential in the development of Japanese prose literature. Finally, one other famous poet of this era with connections to Osaka is Yosa Buson. Born in a village in what is now Osaka City, Buson travelled to Edo to study, and sought to follow in Basho’s footsteps.[54] He became known as one of the great haiku masters, but also as a painter in various styles, ultimately leaving an important footprint on Japanese culture.

Source: OsakaPrints.com https://www.osakaprints.com/content/artists/info_pp/shigeharu_info/shigeharu_16.htm

Yosa Buson is known for his paintings as well as his poetry, but this is not the visual art style most often associated with the Edo Period. A more famous medium from this era is woodcut printing called ukiyo-e; as with the ukiyo-zoshi novels made famous by Ihara Saikaku, this name refers to the “floating world” urban lifestyle of the time. In the same way as with kabuki and rakugo, a distinctive Kamigata scene developed alongside the better-known Edo tradition. One of the key features of Kamigata ukiyo-e is the near-exclusive focus on images of kabuki actors, which in Edo was merely one of many subgenres.[55] For the Osaka merchant class, these actors were effectively local celebrities, with highly organised fan clubs.[56] Another important element of Kamigata ukiyo-e is in how these actors were portrayed: in Edo, where the wild, flashy aragoto acting style was in vogue, artists produced idealised images of the actors, whereas Kamigata’s more delicate wagoto style was reflected in more realistic portrayals of their features and personalities. Indeed, while the artist Sharaku – who was largely unappreciated during his lifetime – is now well-known for his dynamic and even unflattering prints of actors, there were others simultaneously making ukiyo-e in the Kamigata region in much the same style.[57] Apart from these less idealised representations of kabuki actors, other notable features of Kamigata ukiyo-e include the fact that the market was far smaller, and so it was often the case that artists in Osaka were only part-time printmakers. There were also technical innovations that enjoyed greater popularity in Kamigata than in Edo, including the kappazuri style that involved using paper stencils rather than woodblocks to apply colour.[58] Furthermore, as Osaka is so close to Kyoto, works were often influenced by art styles outside of ukiyo-e, such as the Shijo school which tended towards abstract, stylised landscapes, and is descended from the painting style of Yosa Buson.[59] As is the case with many other art forms in the Edo Period, while most academic literature tends to focus on movements in and around Edo, there is also a fascinating history to be seen in Osaka and the wider Kamigata region.

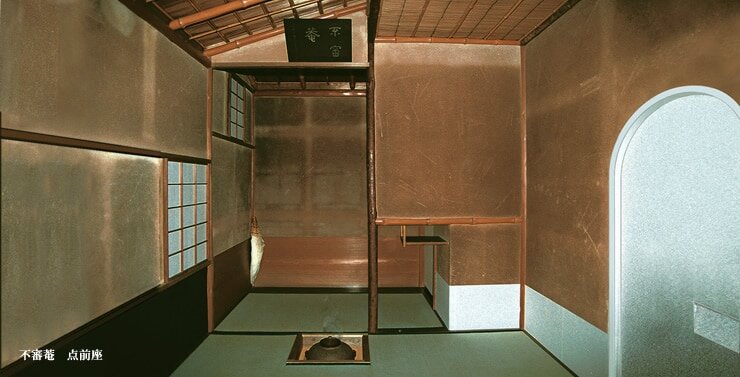

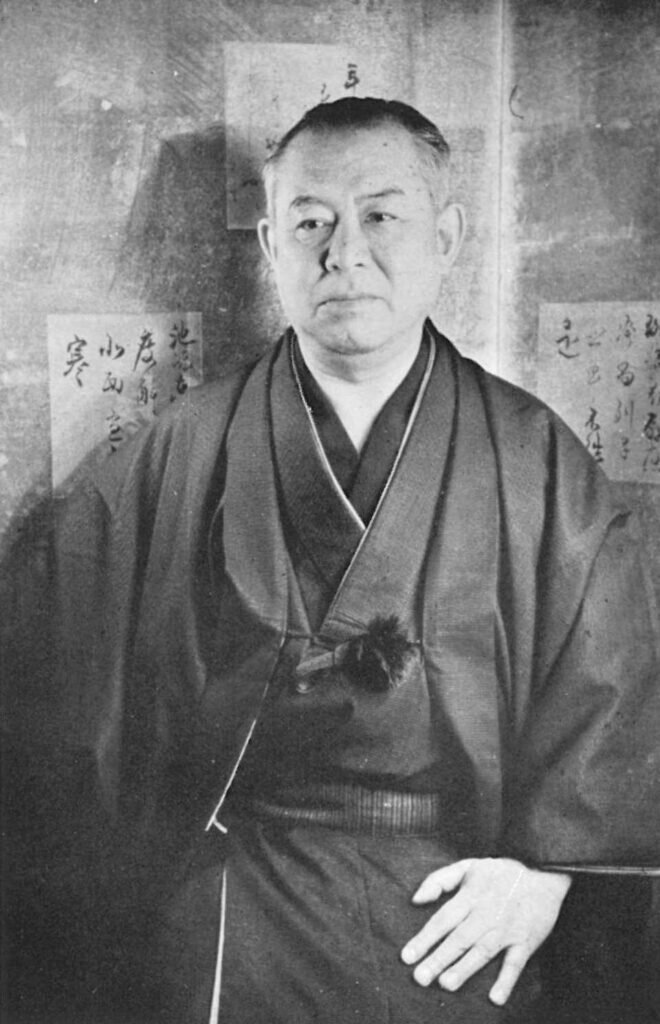

In the forms and styles of art that were popular in Osaka during the Edo Period, there are certain recurring elements. Osaka arts often emphasised greater realism than their counterparts in Edo, while the economic dominance of merchants and Osaka’s relative freedom from the strictness of the class hierarchy resulted in a tendency to subvert or de-emphasise these social rules. Though these ideas grew during the Edo Period, they are also apparent in the aesthetics of tea ceremony, which were codified just before the Edo Period began. Tea was consumed in Japan since around the time Buddhism was being introduced, and the drinking of powdered green tea by elites was gradually formalised based on Zen practices during the 13th-14th centuries CE.[60] The style known most commonly today, though, originated a little later with Sen no Rikyu, the son of a successful merchant in Sakai, south of Osaka.[61] Rikyu learnt the art of the tea ceremony from masters in Sakai and in Kyoto, and was then employed by Oda Nobunaga, one of the central figures in uniting the warring regions of Japan. After Nobunaga was killed in 1582, Rikyu became close to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the second “great unifier” and founder of Osaka Castle, who was a major tea enthusiast.[62] However, their friendship would not last, and eventually Rikyu was ordered to perform ritual suicide in 1591 for reasons that remain unclear. The tea ceremony style pioneered by Rikyu, called wabi-cha, focused on the wabi-sabi aesthetic, emphasising the importance of imperfection with the use of rustic tea ware in contrast with the luxurious items previously preferred by feudal lords.[63] Value was also placed on comfort and hospitality, with tea ceremonies taking place in small, simple, yet carefully arranged rooms. A new feature introduced at this time was the nijiriguchi, a tiny door for guests to enter into the tea room. This forced guests to kneel and crawl into the room, and is also said to have prevented people from concealing swords, with the overall effect of placing everyone at the same level regardless of their place in the social hierarchy. This is in keeping with Rikyu’s intention of making the tea room into a space where social and political matters would not be discussed, which may be the source of his eventual friction with Toyotomi. After Rikyu’s death and the end of the civil war period that soon followed, his tea ceremony style was popularised around the country and through different social classes, including the merchants whose status grew throughout the Edo Period.

Source: Fushin’an official website http://www.omotesenke.com/english/01.html

If we see the Heian Period, with the growth of court culture, as a golden era for Kyoto, and the 20th century as a golden era for the expanding metropolis of Tokyo, it may be fair to say the same of the Edo Period for Osaka. This was when Osaka came to resemble the city it is today, and when it became a major economic centre in the country. It was also a time of cultural development, with Osaka as a shining example of the growing merchant culture of the time. Many of the art forms pioneered in and around Osaka during the Edo Period, such as bunraku, were largely popular arts at the time, but are now perceived as high culture. On the other hand, cultural practices like the tea ceremony were changed from exclusive, upper-class affairs into activities that could be appreciated irrespective of social position. For these reasons, even though the Edo Period is named for the centre of political authority and later official capital city of Japan, it is perhaps Osaka which better represents many of the cultural developments that are remembered and appreciated today.

Osaka Culture in the Twentieth Century

After the Edo Period was brought to an end in the mid-19th century, Tokyo became the new capital, but the newly municipalised city of Osaka continued to grow as an industrial centre. For a short time in the 1920s, when the capital was reeling from the effects of the Great Kanto Earthquake, Osaka’s population even exceeded Tokyo’s.[64] However, this era was quite different from the Edo Period. Japan was a centralised nation and relatively easy to move around; meanwhile, after centuries of self-imposed isolation, new influences were arriving from outside, particularly Europe and America. As a result, cultural forms became relatively uniform, without the stark regional differences seen in earlier times, and often dominated by Tokyo, though there were of course developments occurring in different parts of the country. The aim of this section is to examine creators, works and movements in various fields with a connection to Osaka during the 20th century.

The first area to look at is literature, which evolved significantly in Japan during this time, with Western-inspired forms such as the novel growing in popularity. Among 20th-century Japanese novelists, there are few more renowned than Tanizaki Jun’ichiro and Kawabata Yasunari. Tanizaki was born in Tokyo in 1886, and in his twenties, he began releasing short stories and plays, often incorporating intense themes such as murder and masochism.[65] His full-length novels came later, after his home was destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake and he moved to the Kansai area. Several of his novels are set in Osaka and nearby suburbs, and Tanizaki made an effort to have his characters speak in the local dialect – though especially at first, the inauthenticity was apparent to people in Osaka.[66] His portrayal of Kansai often shows a fascination with the traditional local culture surviving in the area, in contrast with the constantly modernising Tokyo. Initially his viewpoint tended to exoticise Osaka, its people and its traditions, but this perspective became more nuanced with time, coming to reflect a disappointment that traditional culture was being eroded both by outside influences from the rest of the world, and by a growing nationalistic ideology in Japan that left no place for regional differences. This view is particularly apparent in The Makioka Sisters (Sasameyuki), a novel which was serialised during the Second World War, though its publication was suspended on grounds of insufficient patriotism.[67] The Makioka Sisters follows the lives of a bourgeois merchant family from the traditional, high-class Senba area of Osaka, as they seek out a suitable marriage partner for the youngest sister and struggle to maintain their lifestyle while economic opportunities in Kansai dwindle. Now widely considered a classic of Japanese literature, this novel offers insight on the society and culture of Osaka, and issues facing the Kansai region and its people during the 20th century.

Source: Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jun%27ichir%C5%8D_Tanizaki

While works such as The Makioka Sisters create a strong association between Tanizaki and Osaka even though he did not live in the area until well into his thirties, Kawabata Yasunari is the opposite: a celebrated author born and raised in Osaka, who spent most of his life elsewhere.[68] Kawabata was born in 1899 near Osaka Tenmangu and was orphaned at an early age, after which he was raised by his grandparents in Ibaraki City in the north of Osaka Prefecture; his grandparents later died and he moved to Tokyo after completing junior high school.[69] Though Tanizaki’s most famous novels are set in and around Osaka, especially the suburbs between Osaka and Kobe, Kawabata’s take place in many parts of Japan, such as Niigata in Snow Country (Yukiguni) and Kyoto in The Old Capital (Koto). However, both authors often explore the themes of Japanese traditional culture being faced with a changing modern world, as well as dysfunctional desire.[70] They also both had great admiration for The Tale of Genji, with Tanizaki writing a modern Japanese translation of the story, and Kawabata citing it as a major influence on works like Snow Country and The Old Capital.[71] These novels were among the reasons for Kawabata being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1968, making him the first Japanese author to win the award.

Another writer who is less internationally well-known than Tanizaki or Kawabata, but even more closely connected to Osaka, is Oda Sakunosuke. Oda was born in 1913 in southern Osaka City, and found success through his detailed portrayals of ordinary people’s lives in Osaka.[72] He was regarded by critics of the time as a “hooligan writer” for writing about flawed misfits who did not adhere to a national ideal; he shared this appellation with other now celebrated authors such as Dazai Osamu.[73] Before and during the war, his works were therefore heavily censored. Oda is notable also for the markedly regional nature of his work: taking direct inspiration from figures of Osaka’s literary history like Ihara Saikaku and Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Oda’s novels and novellas challenged the Tokyo standard by directly representing the culture, lifestyles and dialect of Osaka. Furthermore, in works like Our Town (Waga Machi), he implicitly critiques the nationalist agenda of the time. This, of course, resulted in harsh criticism, which his close friend Dazai would later blame for Oda’s death in a eulogy. Since 1983, the Oda Sakunosuke Prize has been awarded annually to new authors of fiction, with the goal of perpetuating the literary traditions of Kansai.[74]

Source: Journey Around the World blog https://ameblo.jp/journey-around-the-world/entry-12255169713.html

Other than those mentioned, many other literary figures before and since these authors have connections to Osaka. One of the earliest of these is Yosano Akiko, a poet commemorated alongside Sen no Rikyu as one of Sakai City’s most famous figures.[75] In 1878, she was born into a merchant family who ran a confectionary business, and grew up in Sakai before moving to Tokyo when she was 22 years old. One of her best-known poetry collections is her first, Tangled Hair (Midaregami).[76] In this collection, Yosano uses the traditional poetic form of tanka to express her personal emotions and sexual feelings in a way that was, at the time, widely regarded as shocking for a woman. Yosano went on to be extremely influential in early feminism in Japan. [77] She is also notable as the first to translate The Tale of Genji into modern Japanese, many years before Tanizaki. Another Osaka writer from the early 20th century is Kajii Motojiro, who was born in Osaka in 1901 before moving several times, including returns to Osaka during his teenage years and after university.[78] His life was tragically short, as he died from tuberculosis at the age of 31, and he was therefore underappreciated during his lifetime, but his short stories were soon compiled into a single collection, Lemon (Remon).[79] Kajii’s stories are notable for their strong use of metaphor, as well as the appearance of scientific language stemming from his background in studying physics; they also deal with darkness and sickness, as a reflection of his lifelong illness. His stories found an audience after his death, and today they are well-known, especially the eponymous story from Lemon, which is widely read in schools in Japan.

While the authors mentioned so far mostly represent the literary world of the first half of the 20th century, the increasing market for books in post-war Japan has led to a corresponding proliferation in new authors and styles. Oda Makoto became a bestselling author in the 1960s with a record of his zero-budget travels around the world, before going on to become a renowned peace activist at the forefront of protests against Japan’s involvement in the Vietnam War.[80] His experience as a child during the bombings of Osaka in the Second World War had a major and lasting impact on his views, and he talked in detail about the issue of bombings at the end of the war throughout his life.[81] Osaka was also the home of Tsutsui Yasutaka and Komatsu Sakyo, both considered among Japan’s three great science fiction authors. Komatsu is known for writing Japan Sinks (Nippon Chinbotsu), a novel reflecting Cold War fears about the end of civilisation, and for inspiring mainstream authors to incorporate science fiction elements into their work.[82] Some other writers from Osaka have made a point of emphasising their hometown in their writing. For example, Tanabe Seiko, who won awards for her 1964 novel Sentimental Journey (Senchimentaru Jani) and other later works, became known for the extensive use of Osaka-ben in her novels.[83] More recently, Kawakami Mieko has received widespread praise for novels that explicitly explore feminist themes.[84] Like Tanabe before her, Kawakami’s writing has been noted for the significance of Osaka as a location, with the local dialect and attitudes at the centre of her works.[85] In the same way as earlier authors like Oda Sakunosuke, Tanabe and Kawakami do not shy away from regionally specific elements in their work, making them stand out from other literature in Japan. On the other hand, examples like the science fiction writers mentioned above show that Osaka continues to play a role in starting or accelerating trends in literature.

Source: Amazon.co.jp https://www.amazon.co.jp/s?k=nanri+fumio&i=popular&ref=nb_sb_noss

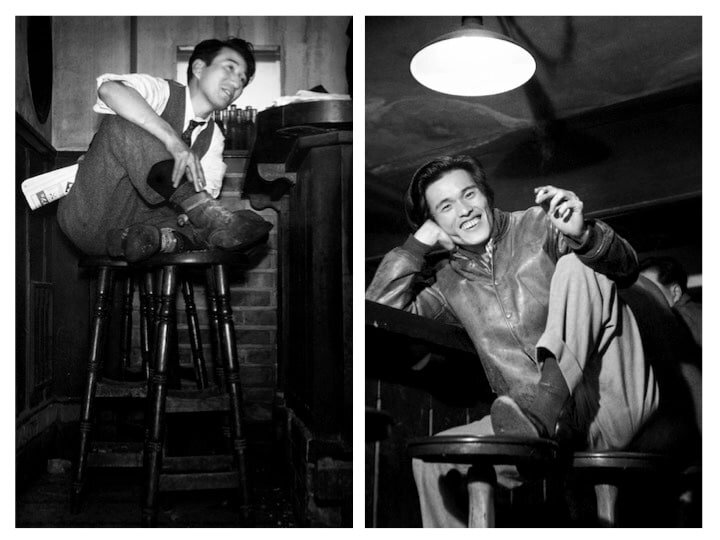

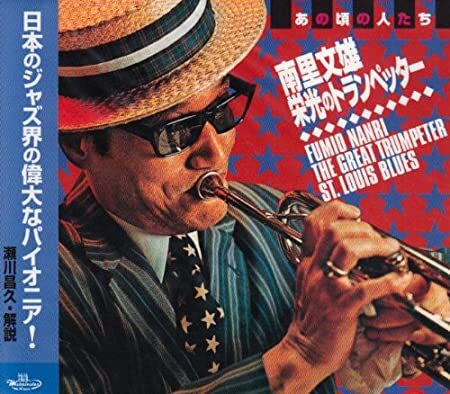

Besides literature, the 20th century saw Western influence affect other art forms too, including music. In the 1910s and 1920s, trans-Pacific luxury ocean liners increased in popularity, and the musicians on board – mostly from the Philippines, an American colony at the time – first brought jazz music to Japan.[86] Because this largely occurred during the 1920s, while Tokyo was rebuilding after the Great Kanto Earthquake, most of the Japanese musicians taking on the new music style were in the Kansai area, rather than the capital. This led to Osaka becoming known as Japan’s “jazz mecca”, where jazz quickly became popular in the dance halls of Dotonbori, and the music was increasingly performed by local musicians.[87] There was initially a backlash, partly from an anti-American perspective, but also from music scholars who regarded jazz as inferior to Western classical music. Despite this hostile reaction, though, jazz soon rebounded and became popular throughout the country, especially in places like Osaka, Kobe and Yokohama. Some of the early big names of Japanese jazz were Osaka natives, such as composer Hattori Ryoichi and trumpeter Nanri Fumio.[88] The latter was one of the first Japanese jazz musicians to make a name for himself internationally, after advancing his career in Shanghai and Dalian in China, and although the Second World War began soon after his return and put a stop to jazz, his success continued after the war.[89] Nanri was nicknamed the “Satchmo of Japan” by Louis Armstrong himself, and the two performed together in 1954. Though the years since have seen the focus of jazz in Japan move away to Kobe and, especially, Tokyo, Osaka’s fundamental role in Japanese jazz history was later recognised by UNESCO, who chose it as the host city for the third International Jazz Day in 2014.[90]

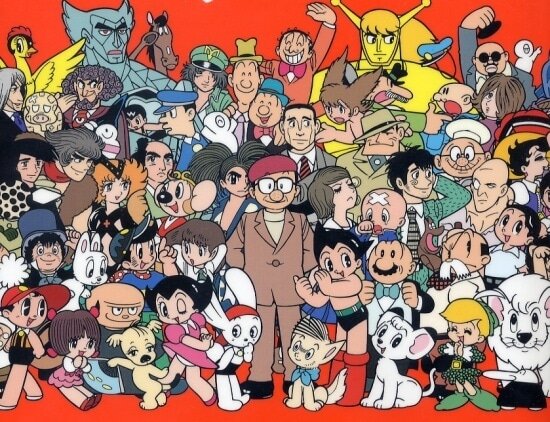

Manga is another Western-influenced art form that took off in the 20th century, though it soon grew into something quite different from comic books in Europe and America. One individual especially revered for his pioneering ideas and unparalleled influence in manga is Tezuka Osamu, the creator of Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu), Black Jack (Burakku Jakku) and a great many others. Born in 1928 in Toyonaka City in the north of Osaka Prefecture, Tezuka’s family moved to nearby Takarazuka in Hyogo Prefecture when he was 5 years old, though he continued to attend school in Osaka.[91] Both of these locations had an important impact on the works he would later create, with the famous all-female musical theatre of the Takarazuka Revue influencing his art, and his wartime experiences in Osaka inspiring themes that he would return to often.[92] Like Oda Makoto, Tezuka witnessed the bombing of Osaka first-hand, later writing an autobiographical manga depicting his experience of surviving a direct attack on the army arsenal where he was placed as a teenager, seeing the destruction from the watchtower.[93] He also addressed themes of peace and war, and mistrust of political and military leaders, in works such as Astro Boy, which would go on to be extremely influential in the world of manga and anime and known worldwide. Between 1945 and 1951, Tezuka studied medicine at Osaka University, but he was already enthusiastic about creating manga before university, and during his studies he juggled the two interests.[94] Eventually, with encouragement from his mother, he opted to follow his passion, and when a publishing company sent somebody to seek him out soon after graduation, he moved to Tokyo. His medical knowledge still played a role in his work though, for example in Black Jack, a series focusing on an unlicensed surgeon. Tezuka’s work as an artist, storyteller and animator laid the groundwork for generations after him, while he continued to innovate throughout his career. His life and work are commemorated today at the Tezuka Osamu Manga Museum in Takarazuka.[95]

Source: Tezuka In English http://tezukainenglish.com/wp/?page_id=912

Other well-known manga writers from Osaka include Tatsumi Yoshihiro, who is known for pioneering the gekiga genre of more realistic and mature comics. Tatsumi himself has suggested that the background of Osaka enabled this movement, as while Tokyo publishers generally produced well-packaged, mainstream works, the mixed-quality releases common in Osaka enabled the growth of an alternative style.[96] Gekiga was clearly in opposition to the generally child-friendly style of Tezuka and other mainstream cartoonists, but later in his career, even Tezuka went on to create gekiga works inspired by Tatsumi and Osaka artists like him.[97] Osaka writers were also influential in a very different genre from gekiga: that of shojo manga aimed primarily at girls. This is another area where Tezuka played a major role, notably with Princess Knight (Ribon no Kishi), in which his memories of the Takarazuka Revue inspired a story groundbreaking for its use of a cinematic narrative in the shojo genre.[98] A later writer who went far further was Ikeda Riyoko, whose Rose of Versailles (Berusaiyu no Bara) achieved great success in the early 1970s with its elaborate story based on the French Revolution.[99] Miuchi Suzue is another influential shojo manga author from Osaka, known for Glass Mask (Garasu no Kamen), which began serialisation in the 1970s and remains incomplete today.[100] Of course, these are only a few examples of the most well-known figures, but there are many other popular manga writers from Osaka, both in the past and in the present.

Whereas this section up to now has concentrated on Osaka’s contributions to nationwide – and indeed, worldwide – art forms, there is one famous development in 20th-century culture that is very closely tied to Osaka specifically. This is manzai, the main Japanese equivalent to Western stand-up comedy, which normally takes the form of a dialogue where one comedian (called the tsukkomi) reacts to the foolishness of the other (the boke).[101] The origins of manzai lie in a type of performance at traditional festivals, in which two performers would bless the community through a conversation between heaven and earth; over time the relationship between the two speakers became a source of humour, which was increasingly emphasised.[102] This form of entertainment became secularised, and during the late 19th century, innovators in Osaka incorporated elements of other genres and began applying the terms boke and tsukkomi to the two roles. Then, in the 1930s, the duo of Yokoyama Entatsu and Hanabishi Achako revolutionised manzai by making comedy the main focus, rather than an interlude between other performances, as well as wearing Western clothes and performing on the radio. Around this time, the Osaka-based entertainment company Yoshimoto Kogyo shifted their focus to the new manzai style from rakugo; the company would go on to be huge in the Japanese entertainment industry.[103] After the Second World War, televised manzai became popular, providing new acts like Yokoyama Yasushi and Nishikawa Kiyoshi (called “Yasukiyo” together), who used the new format to emphasise the physical aspect of the performance that could not be captured on the radio. In some ways, television was detrimental to manzai, as it could not fully recreate the experience of seeing the performers live on stage, and the traditional master-pupil mode of instruction faded, but Yoshimoto Kogyo’s NSC (New Star Creation) school then produced many acts who successfully took advantage of the possibilities of television. Among the early NSC graduates are one of the most famous comedy duos, Downtown, consisting of Hamada Masatoshi and Matsumoto Hitoshi, who became known for their strange and outrageous sketches, and in doing so established Osaka-ben in many people’s minds as the primary language of comedy.[104] Television comedy has continued to grow since these forerunners, and this will be explored a little further in the final section.

Since the end of the Edo Period, Tokyo has generally dominated Japan’s cultural landscape, and as a result is often taken for granted as the centre of culture. While this is not without reason, the 20th century also saw a great deal of literature, art and entertainment being produced elsewhere in the country. Osaka, formerly the origin or site of innovation of many art forms, became secondary during this time, and yet many influential figures are connected to the city. Furthermore, while many of Osaka’s cultural contributions were in areas already concentrated mainly in the capital, entertainment forms like manzai and alternative genres such as gekiga developed in Osaka, bringing the cultural logic of the region to the rest of Japan.

Background of Contemporary Culture in Osaka

So far, we have looked at Osaka’s cultural history from the classical era until near the present day. This leaves today’s Osaka, which in the popular imagination is associated with several things mentioned at the beginning of this essay, such as food and comedy. This final section will give an overview of a small selection of these, with a brief description of the history behind them, in order to provide a picture of what entails “Osaka culture” today.

Source: official Twitter account https://twitter.com/gakitsukatter

First, we will return to the subject of comedy. As explained earlier, Osaka played a defining role in the growth of the manzai comedy format, which moved to radio and television, and became the standard mode of Japanese comedy. While the style of manzai – with the roles of boke and tsukkomi – remains central to comedy today, television ultimately has had a major impact. Comedians have certainly not disappeared though, and the NSC school of Yoshimoto Kogyo continues to produce popular acts, who go on to appear in all kinds of roles on television, as hosts, guests, participants on games shows, and more.[105] In fact, despite the declining popularity of live comedy, comedians seem to be more omnipresent than ever, with Yoshimoto Kogyo’s various acts appearing almost constantly on prime-time programmes. A great number of these acts still perform as duos, as in manzai, and following the success of Downtown, it continues to be the case that many popular comedians hail from Osaka, contributing to the city’s reputation for humour.[106] With the options for work branching out beyond comedy shows into other media, some individual comedians have also found success outside of the double acts that first made them known. For example, Matayoshi Naoki initially played the boke role in the duo Peace, but after an offer to turn his creative writing talents to a new format, he wrote Spark (Hibana), a novel about a struggling young manzai performer from Osaka that won the prestigious Akutagawa Prize and was adapted into a successful Netflix series.[107]

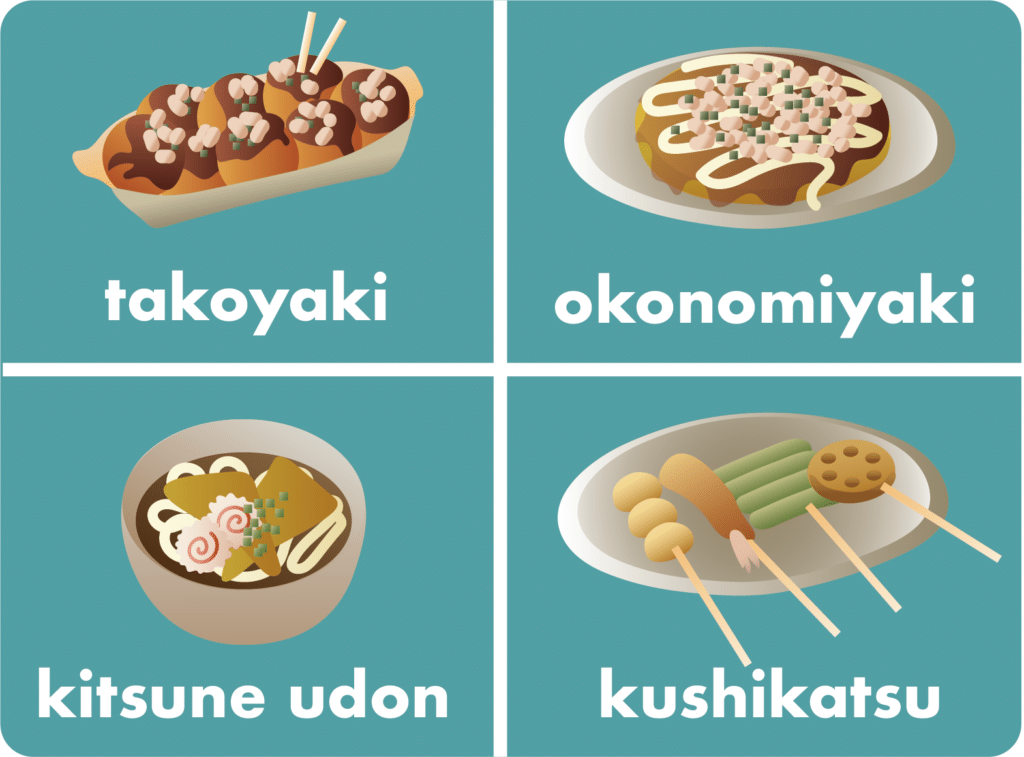

Besides comedy, Osaka is well-known for its food, with many dishes originating in the area now being popular throughout Japan and beyond. Its reputation for good food goes back hundreds of years to the Edo Period, when Osaka was known as “the nation’s kitchen”.[108] Some of the famous Osaka products at that time include kelp dashi, regarded as a crucial part of the flavour of Japanese cuisine, and sake made using local rice and high-quality water. This focus on food in the society of Osaka gave rise to the cliché that while people from Kyoto spend all their money on clothes and people from Tokyo (Kobe in some versions) spend all their money on shoes, people from Osaka instead spend it on food.[109] More recent arrivals to Osaka’s culinary culture include kitsune udon. This dish of udon noodles in a light broth, topped with deep-fried tofu, is said to have originated in an Osaka restaurant around the turn of the 20th century, and reflects the Osaka taste for a milder-flavoured dashi compared with Eastern Japan.[110] Another speciality is kushikatsu: the restaurant Daruma claims to have invented this deep-fried dish of skewered meats and other items in 1929 as a cheap meal for labourers in Shinsekai, which was then a new and prosperous district.[111] The neighbourhood’s reputation suffered since that time, but it is still famous for kushikatsu, which has become one of Osaka’s representative dishes. Osaka is also known for popular batter-based dishes including takoyaki and okonomiyaki. The latter is a kind of savoury pancake topped with a slightly sweet sauce, believed to have evolved from earlier dishes which gained popularity in the Edo Period, mainly in Edo, before being spread from Tokyo to the Kansai area after the Great Kanto Earthquake.[112] In Osaka, ingredients were changed and the new dish was loved by the locals; after the World Expo in 1970, okonomiyaki became known widely as an Osaka speciality.[113] Dishes like okonomiyaki and takoyaki are especially popular at food stalls during festivals, where they can be found not only in Osaka but as standard fare throughout the country.[114] Looking at the background behind this small selection of dishes, certain trends can be seen, such as a tendency towards milder and sweeter flavours. Inexpensive items are also popular, fitting Osaka’s history as a centre of first commerce and then industry, where customers would appreciate a good deal.

While comedy and cuisine are notable aspects of Osaka’s local culture, it would be a major oversight not to mention the significance of foreign cultures too. In particular, Osaka is notable for its large resident population of Korean descent, many of whom live in the city’s Ikuno Ward.[115] Koreans in Osaka and elsewhere in Japan have historically faced difficulties due to legal ambiguities over their situation, active discrimination and other reasons, but in most cases, social attitudes have improved, and Korean culture is now popular with many Japanese people.[116] The Tsuruhashi neighbourhood in Ikuno Ward boasts a busy Korea Town, where shops and stalls offer pop culture merchandise and Korean cuisine among other things. Another neighbourhood where foreign influence can be clearly felt is so-called Amerikamura (“American Village”) near the upscale Shinsaibashi shopping district. Beginning in the 1960s, this area became the site of popular shops, whose owners promoted the growth of a shopping area tailored to the youth.[117] Items like clothes and records, especially those imported from the United States, became a major part of what these shops carried, and in the 1980s, the Amerikamura name caught on in the media. Today it is still a popular site of youth culture in Osaka, and although the “American” connection is looser than in the past, many restaurants and bars in the area serve unusual international food.[118] Areas like Korea Town in Tsuruhashi and Amerikamura may seem quite different from other areas that demonstrate mainstream contemporary culture, but considering Osaka’s long history as an international port city, this is perhaps not terribly surprising. Even in its early days as the port town of Naniwa-zu in the 5th to 8th centuries CE, the Osaka area had foreign residents as a result of its diplomatic significance, and this international link has continued in various forms since.[119] Therefore, while it might be tempting initially to view signs of foreign culture as something separate, it would be more appropriate to see this as a crucial part of Osaka culture itself.

Summary and Conclusion

Osaka’s cultural history can be seen broadly in two ways: as one part of Japanese cultural history, or as a separate entity that interacts with the rest of Japan. On the one hand, Osaka has influenced many art forms through the ages, either directly through individuals bringing innovations to popular forms, or through great artists’ experiences of Osaka. However, in some cases Osaka has developed its own traditions, like manzai, which are certainly connected to culture in the rest of the country, but have evolved quite separately and are still strongly associated with Osaka however much they spread. Indeed, the strong sense of regionalism that comes across through the use of local language and emphasis on the customs of the area as opposed to the nation can give the impression that creators in Osaka belong to Osaka first, and anything else second.

Source: Costume Museum http://www.iz2.or.jp/gyojibunka/kyutei17.html

Apart from the feeling of regional identity, other hallmarks of Osaka culture through the ages include an emphasis on simplicity and realism, which often entails the use of humour. Many aspects of Osaka culture find their roots in the merchant culture of the Edo Period, which can help to explain a tendency towards de-emphasising class distinctions. There are also elements that reflect particular historical events, such as the movement of people from Tokyo after the Great Kanto Earthquake resulting in the novels of Tanizaki Shin’ichiro, the Osaka jazz boom and the creation of okonomiyaki; and the bombing campaigns on Osaka during the Second World War inspiring anti-war narratives in later artistic works. While Osaka has influenced culture outside of the area in many ways, it has also been influenced by many sources, whether it be Buddhist culture millennia ago, painting styles from Kyoto in the Edo Period, or fashion and food from overseas in the 20th century and today. Overall, it is fair to say that Osaka culture can mean many different things, and ultimately this is connected to all other aspects of its history and development.

Osaka history series part 1: LINK

Except where otherwise noted, graphics are by Rachel Stewart (https://www.rachelstewartphd.com/) and other images are photographs taken by the author.

[1] 2017. ‘Japanese Dialects’. Nippon.com.

[2] 2020. ‘Rankings of Hard-to-Understand Dialects’. Goo Rankings.

[3] Moor, L, 2020. ‘Learn Japanese: An Introduction to Japanese Dialects’. Tokyo Weekender.

https://www.tokyoweekender.com/2020/05/learn-japanese-dialects/

[4] ‘Japanese Dialects – A brief overview of the major dialects in Japan’. ArcGIS StoryMaps.

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=5b76cda68731482d864c98b19e0dbfa8

[5] Seeley, C, 1984. ‘The Japanese Script since 1900’. Visible Language.

https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/visiblelanguage/pdf/18.3/japanese-script-since-1900.pdf

[6] Rochelle, 2014. ‘Kobun (Classical Japanese) – Old Kana’. Tofugu.

[7] Shingu, I. ‘Past Affirmative Form’. Kansai Dialect.

http://www.kansaiben.com/3.BasicGrammar/1a.Verb/2.Grammar/3G.html

[8] Strycharz, A, 2011. ‘Variation and change in Osaka Japanese honorifics: A sociolinguistic study of dialect contact’. University of Edinburgh.

[9] Shibatani, M, 1990. The Languages of Japan. Cambridge University Press.

[10] Shingu, I. ‘Kansai-ben films’. Kansai Dialect.

[11] ‘Historical Overview’. Osaka City official website.

https://www.city.osaka.lg.jp/contents/wdu020/enjoy/en/overview/content_Historical_overview.html

[12] Brock, K. ‘Japan, Buddhist Art In’. Encyclopedia.com.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/japan-buddhist-art

[13] Schumacher, M. ‘Kannon Notebook’. Japanese Buddhist Statuary.

[14] ‘Abiko Kannon’. Sumiyoshi Ward official website.

https://www.city.osaka.lg.jp/contents/wdu020/sumiyoshi/english/attract/attrac15.html

[15] 2013. ‘Japan’s Oldest Kannon Temple: Taisho Kannonji’. Sanpo Biyori.

[16] Baquet, B, 2019. ‘The Saigoku 33 Kannon Route’. The Temple Guy.

[17] 2018. ‘Thousand-Armed Kannon Deity Takes Divine Omnipresence to a Whole New Level’. Waraku.

[18] ‘Japan’s National Treasures (Sculptures)’.

[19] ‘Wani’s Grave’. Osaka Convention & Tourism Bureau.

[20] Ogura Hyakunin Isshu.

http://jti.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/hyakunin/frames/hyakuframes.html

[21] Blankestijn, A, 2016. ‘Hyakunin Isshi (One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each): Poem 19 (Lady Ise)’. Japanese and European Culture.

https://adblankestijn.blogspot.com/2016/06/hyakunin-isshu-one-hundred-poets-one.html?

[22] ‘The Tale of Sumiyoshi’. Met Museum Collection.

[23] ‘Sumiyoshi Shrine, Osaka’. Tale of Genji.org.

[24] ‘The Pilgrimage to Sumiyoshi (Miotsukushi), Illustration to Chapter 14 of the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari)’. Harvard Art Museums.

[25] Sadler, A (translator), 1918. The Tale of the Heike. The Asiatic Society of Japan (archive).

https://web.archive.org/web/20100807003350/http://libweb.uoregon.edu/ec/e-asia/read/heike-whole.pdf

[26] 2016. ‘A Closer Look: Moon Above the Sea at Daimotsu Bay’. Ronin Gallery.

https://www.roningallery.com/education/a-closer-look-moon-above-the-sea-at-daimotsu-bay/

[27] ‘Edo Period’. The Samurai Archives.

https://wiki.samurai-archives.com/index.php?title=Edo_period

[28] ‘Chonin’. The Samurai Archives.

[29] Lombard, F, 1928. ‘Kabuki: A History’. TheatreHistory.com.

[30] ‘Invitation to Kabuki: Establishment’. Japan Arts Council.

https://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/unesco/kabuki/en/history/history2.html#a

[31] ‘Wagoto’. Kabuki21 Kabuki Glossary.

[32] ‘The history of Shochiku’. Shochiku official website.

[33] ‘Kamigata’. Kabuki21 Kabuki Glossary.

[34] Johnson, M, 1995. ‘A Brief Introduction to the History of Bunraku’. The Puppetry Home Page.

https://www.sagecraft.com/puppetry/definitions/Bunraku.hist.html

[35] ‘Takemotoza’. Kabuki21 Kabuki Glossary.

[36] ‘Samisen music’. Encyclopædia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/art/Japanese-music/Samisen-music#ref603013

[37] Harano, J, 2014. ‘The Rich History and Uncertain Future of Bunraku Puppet Theater’. Nippon.com.

[38] ‘First great love suicide drama: Sonezaki shinju’. Kabuki on the web.

[39] ‘About “Tsuyu no Tenjinja” and Chikamatsu Monzaemon “Sonezaki Shinju”’. Tsuyu no Tenjinja official website.

[40] ‘Invitation to Kabuki: Eminent Playwrights’. Japan Arts Council.

https://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/unesco/kabuki/en/play/playwright.html

[41] ‘Namiki Sosuke’. Kabuki21.

[42] ‘Invitation to Kabuki: Finalization Period’. Japan Arts Council.

https://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/unesco/bunraku/en/history/history4.html

[43] 2015. ‘“Rakugo” (The Art of Storytelling)’. Nippon.com.

[44] Shores, M, 2014. ‘A critical study of Kamigata rakugo and its traditions’. University of Hawaii.

[45] ‘Akashi-bikyaku’. Rakugo Sanpo.

[46] ‘Rakugo Theatre Temma Tenjin Hanjo Tei’. Osaka Convention & Tourism Bureau.

https://osaka-info.jp/en/page/rakugo-theater-temma-tenjin-hanjo-tei

[47] ‘Rakugo Museum’. Ikeda City Tourist Association.

[48] ‘Basho’. Encyclopædia Britannica.

[49] ‘Ueshima Onitsura’. Itami City official website.

http://www.city.itami.lg.jp/shokai/gaiyorekishibunka/rekishi/1392285884285.html

[50] ‘Tomb of Ueshima Onitsura’. Osaka City official website.

https://www.city.osaka.lg.jp/contents/wdu020/kensetsu/english/rekishi/uekita/p71e.htm

[51] Shirane, H, 1992. ‘Matsuo Basho and the Poetics of Scent’. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2719329?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

[52] ‘Ihara Saikaku’. Encyclopædia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ihara-Saikaku#ref213915

[53] ‘Ihara Saikaku’. My Poetic Side.

[54] Larking, M, 2016. ‘Yosa Buson: A Japan-China relationship that works’. The Japan Times.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2016/09/13/arts/yosa-buson-japan-china-relationship-works/

[55] Fiorillo, J. ‘Osaka Prints (Kamigata-e)’. Viewing Japanese Prints.

https://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/ukiyoe/intro_osaka.html

[56] Ujlaki, P, 1999. ‘Actor Idolatry: A Woodcut Bonus’. OsakaPrints.com.

http://www.osakaprints.com/content/information/articles/article_texts/idolatry.htm

[57] ‘Kamigata Prints’. Artelino.

[58] ‘Kappazuri’. Japan Architecture and Art Net Users System.

[59] ‘Shijo Prints – Japanese Expressionism’. Artelino.

[60] ‘Tea culture’. The Samurai Archives.

https://wiki.samurai-archives.com/index.php?title=Tea_ceremony

[61] Caicedo, R. ‘Sen no Rikyu: The Greatest Japanese Tea Master’. My Japanese Green Tea.

[62] ‘The tea ceremony’. The Samurai Archives.

https://www.samurai-archives.com/tea.html

[63] Kinoshita, A, 2014. ‘Sen no Rikyu – The Greatest Tea Master’. Kyoto University of Foreign Studies.

http://thekyotoproject.org/english/sen-no-rikyu-the-greatest-tea-master/

[64] Hashizume, S, 2019. ‘A History of Osaka, Japan’s City of Water’. Nippon.com.

https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/g00681/a-history-of-osaka-japan%E2%80%99s-city-of-water.html

[65] ‘Junichiro Tanizaki’. Encyclopedia.com.

[66] Wei, R, 2018. ‘An Outside and Insider’s Osaka: Osaka in Tanizaki Jun’ichiro and Oda Sakunosuke’s Literature’. University of Oregon.

[67] ‘Jun’ichiro Tanizaki’. The Modern Novel.

https://www.themodernnovel.org/asia/other-asia/japan/tanizaki/

[68] ‘Ibaraki Municipal Kawabata Literature Memorial Hall’. Osaka Convention & Tourism Bureau.

https://osaka-info.jp/en/page/ibaraki-municipal-kawabata-literature-memorial-hall

[69] 2018. ‘Profile of Yasunari Kawabata’. Ibaraki City official website.

https://www.city.ibaraki.osaka.jp/kikou/shimin/bunka/menu/kawabata/profilekawabata.html

[70] Williams, M, 2016. ‘Beauty & Sadness in Yasunari Kawabata’. Japan Spotlight.

https://www.jef.or.jp/journal/pdf/205th_Special_article_03.pdf

[71] ‘Yasunari Kawabata’. The Nobel Prize.

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1968/kawabata/biographical/

[72] 2013. ‘100th Anniversary Exhibition: Sakunosuke Oda and Greater Osaka’. Osaka Museum of History.

http://www.mus-his.city.osaka.jp/eng/exhibitions/special/2013/odasaku.html

[73] 2018. ‘Sakunosuke Oda: The Unconventional Writer’. Yabai.com.

[74] ‘Literary Awards’. JLit.net.

http://www.jlit.net/reference/literary-awards/literary-awards-n-to-z.html

[75] Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko official website.

[76] ‘Yosano Akiko’. Poetry Foundation.

[77] Kitagawa, S, 2009. ‘Living as a Woman and Thinking as a Mother in Japan’. Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture.

[78] 2018. ‘The Short Life of Motojiro Kajii: A Purveyor of Japanese Culture’. Yabai.com.

[79] Morrison, L, 2013. ‘Kajii Motojiro, Poet of Darkness: Four Translations and a Commentary’. ICU Comparative Culture.

[80] Kometani, F, 2002. ‘The Courage of His Convictions’. Time Asia (archive).

https://web.archive.org/web/20021014225023/http://www.time.com/time/asia/features/heroes/oda.html

[81] Tanaka, Y, 2007. ‘Oda Makoto, Beheiren and 14 August 1945: Humanitarian Wrath against Indiscriminate Bombing’. The Asia-Pacific Journal.

[82] Bolton C (translator) et al, 2002. ‘An Interview with Komatsu Sakyo’. Science Fiction Studies.

https://www.depauw.edu/sfs/backissues/88/komatsu%20interview.htm

[83] ‘Seiko Tanabe’. Japanese Literature Publishing Project.

[84] Rollmann, H, 2020. ‘Mieko Kawakami’s “Breasts and Eggs” Is a Feminist Masterpiece’. PopMatters.

https://www.popmatters.com/mieko-kawakami-breasts-and-eggs-2645864559.html

[85] Kosaka, K, 2020. ‘“Breasts and Eggs”: Not just some elevated piece of literary chick-lit’. The Japan Times.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2020/05/02/books/book-reviews/breasts-and-eggs-mieko-kawakami/

[86] Jarenwattananon, P, 2014. ‘How Japan Came To Love Jazz’. NPR.

https://www.npr.org/sections/ablogsupreme/2014/04/30/308275726/how-japan-came-to-love-jazz

[87] Ackermann, K, 2018. ‘Big In Japan, Part 2: Osaka & The Eri Yamamoto Connection’. All About Jazz.

[88] 2014. ‘International Jazz Day 2014 – Main Events hosted by Japan in Osaka’. UNESCO.

https://en.unesco.org/events/international-jazz-day-2014-main-events-hosted-japan-osaka

[89] Sugiyama, K, 2003. ‘Nanri, Fumio’. Grove Music Online.

[90] 2014. ‘Spring of Jazz in Osaka’. UNESCO.

http://www.unesco.org/new/en/media-services/in-focus-articles/spring-of-jazz-in-osaka/

[91] ‘History: 1930s’. Tezuka Osamu official website.

[92] ‘Tezuka’s Life (1928 – 1957)’. Tezuka In English.

[93] Tanaka, Y, 2010. ‘War and Peace in the Art of Tezuka Osamu: The humanism of his epic manga’. The Asia-Pacific Journal.

[94] ‘History: 1940s’. Tezuka Osamu official website.

[95] ‘Tezuka Osamu Museum’. Osaka Convention & Tourism Bureau.

[96] Suzuki, S, 2011. ‘Tatsumi Yoshihiro’s Gekiga and the Global Sixties: Aspiring for an Alternative’. Kyoto Seika University International Manga Research Center.

http://imrc.jp/images/upload/lecture/data/SUZUKI20111212.pdf

[97] Wells, D, 2014. ‘Meet the men behind manga: Gekiga exhibition launches at London Cartoon Museum’. London, Hollywood.

[98] ‘Princess Knight [Shojo Club] (Manga)’. Tezuka In English.

[99] ‘The Author and her Work’. Mariko Shinobu (Oniisama E fansite).

[100] Okabayashi, K, 2007. Manga for Dummies. Wiley Publishing.

[101] Tetsu, S, 2016. ‘A (Half-Assed) History of Manzai: Entatsu and Achako’. Stephen Tetsu blog.

https://stephentetsu.com/2016/12/01/a-half-assed-history-of-manzai-entatsu-and-achako/

[102] Bensky, X, 2001. ‘Commodified Comedians and Mediatized Manzai: Osakan Comic Duos and their Audience’. University of Washington (archive).

https://archive.is/20010504063016/http://mcel.pacificu.edu/aspac/papers/scholars/bensky/bensky.htm

[103] ‘Yoshimoto Kogyo’. Japan Zone.

[104] ‘Downtown’. Japan Zone.

[105] Corkill, E, 2011. ‘Yoshimoto Kogyo’s New Star Creation: Comedy’s a funny business in Japan’. The Japan Times.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2011/11/27/general/yoshimoto-kogyo-new-star-creation/

[106] ‘Comedians’. Japan Zone.

[107] Hernon, M, 2016. ‘Q&A: Naoki Matayoshi on His Novel “Hibana”, and the Netflix Series’. Tokyo Weekender.

[108] ‘Tradition and History Create Osaka’s Famous Flavors’. Osaka Convention & Tourism Bureau.

[109] Downey, T, 2013. ‘Taste of Osaka’s Dining Scene’. The Wall Street Journal.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323469804578523552850584648

[110] Sugiura, T. ‘A study of Osaka epicurism: Kitsune Udon’. Tsuji Group.

[111] 2015. ‘Kushiage: The Best Japanese Deep Fried Food on a Stick!’ Gurunavi.

[112] ‘History of Okonomiyaki’. Okonomiyaki – What You Want Grilled.

https://whatyouwantgrilled.wordpress.com/history-of-okonomiyaki/

[113] ‘Okonomiyaki’. Osaka Convention & Tourism Bureau.

[114] Jena, N (translator), 2017. ‘Popular Festival Food In Japan’. Matcha.

[115] 2019. ‘South and North Korean Residents in Japan’. Statistics Japan.

[116] Kin, Y, 2018. ‘Scenes of Heisei: Food serves as political bridge in Osaka’s busting Koreatown’. Mainichi Japan.

https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20181024/p2a/00m/0na/005000c

[117] ‘History’. Amerikamura no Kai.

[118] ‘America-mura’. GaijinPot Travel.

[119] Sakaehara, T, 2008. ‘The port of Osaka: From ancient times to today’. In: Graf, A and Huat, CB, ed. Port Cities in Asia and Europe. Routledge.