English teaching is a common profession for foreign residents in Japan for a few reasons. Jobs may be available even for people without specific teaching qualifications, English ability is often the most crucial quality for getting hired, and in many cases they don’t require you to be able to speak Japanese.

But what is it like to be an English teacher in Osaka? In this article I would like to give you a sense of my own experience of teaching English both at an Eikaiwa company and at regular Japanese schools. Hopefully this can help you out if you’re thinking about working as an English teacher yourself.

Table of Contents

The different kinds of English teaching

There are many different kinds of English teacher in Japan, whether you’re working at a school, a university, or a private company, just to give a few examples. However, for most people there are two realistic entry-level options for securing a teaching job: working as an Eikaiwa teacher or as an ALT.

“Eikaiwa” is a Japanese term for a private English conversation school. These range from companies with branches all over the country, to small local businesses. They generally offer a range of lessons including focused courses and looser practice sessions. The priority is usually spoken English, and Eikaiwa companies typically emphasise small class sizes, with even one-on-one lessons (often called “man-to-man” in Japanese) being common for adults. Some companies also offer lessons for other languages than English too.

Larger Eikaiwa companies might advertise outside Japan and may even be able to sponsor your visa if you are hired, so they can be a good opportunity if you want to live in Japan but are struggling to find work. These jobs are also easy to come across if you’re already in the country.

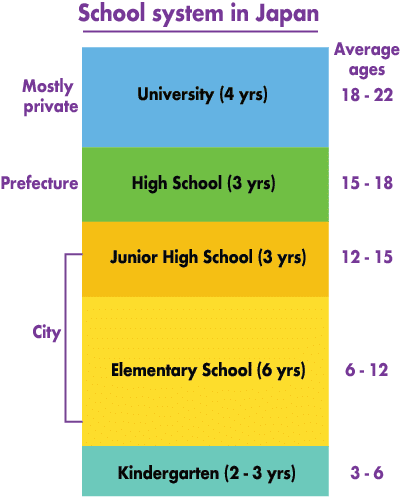

The other common type of English teaching is ALT work. An ALT is an “assistant language teacher” – meaning a teacher who is proficient in English and who helps the existing Japanese staff at a regular school. The school you work at could be public or private, and ALT work can range from kindergarten all the way up to senior high school. Depending on which level of school you’re teaching in, the expectations for what kind of help the school needs from you can vary. You might be essentially the main teacher while the homeroom teacher helps with crowd control, or you might just be called upon now and again to provide examples of spoken English.

A popular way to apply for ALT work from outside Japan is the JET Programme, a government initiative that hires English teachers from around the world to work in Japanese schools. An advantage of this is that the basic requirements are quite low – holding any bachelor’s degree, being from one of the countries where they recruit, and speaking English – but one possible disadvantage is not being able to choose where you get posted.

There are also private dispatch companies that hire ALTs both in Japan and overseas. They can offer the certainty of knowing the area you’ll work in, but like Eikaiwa companies, they don’t provide the same comfort as the JET Programme of knowing that the government is in charge.

One other possibility for ALT teaching is being hired directly by a local Board of Education. However, this is likely to be available only to people already in Japan, positions will be extremely limited, and the requirements are often quite a bit higher.

My personal experience comes from working for an Eikaiwa company, and then as an ALT for a private dispatch company. Let me give you an idea of what these were like.

My experience as an Eikaiwa teacher

Before going to Japan to work, I had already lived in the country once before – as a university exchange student in Kyoto. After living in Kyoto for a year, I was sure that I wanted to be in the Kansai area again. When other job applications didn’t work out, I tried out an Eikaiwa company, knowing they could give me a good chance of getting to live and work in Kansai. A few months later, I packed my bags and moved to Osaka.

A benefit of getting this job was that I received quite a lot of training before actually being assigned to branches, which I really needed as I hadn’t worked as a teacher before. When I finally got my first shifts, I found myself working in branches all over Kansai, from Kyoto to Himeji to Nara to Wakayama. Even once my longer-term schedule was fixed, there was usually a lot of commuting. Exhausting!

The timetable was often quite difficult too. As Eikaiwa companies generally offer lessons at times when children are not in school and adults are not at work, their weekday business hours tend to run from mid-afternoon into the evening, and most employees have to work at least one day at the weekend. On the bright side, I joined the company before they introduced new contracts with longer hours, so I would start later and finish earlier than new teachers who joined after me.

My schedule contained several regular courses, mostly for children, but with a few for middle school students and adults too, nearly all using the company’s own teaching materials. There were also many slots where adult students could book a conversation lesson, also using the company’s books except for higher-level students who preferred to work at their own pace. On a busy day, there would be very little time in between classes, but on the other hand, quiet days often left me with very little to do during my downtime.

An average Eikaiwa day

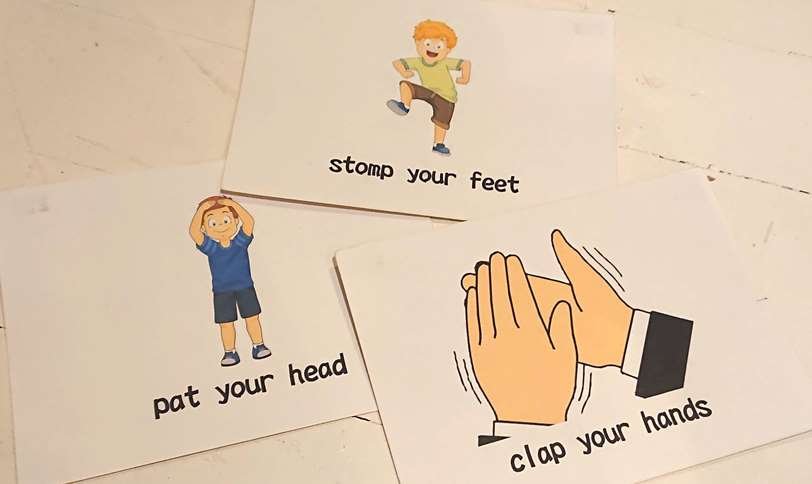

A typical day for me working as an Eikaiwa teacher was something like this. I would arrive in the mid-afternoon (or in the morning on a Saturday), and usually I would have 15 or 20 minutes before teaching one of several kids’ classes. In that time, I would get the kids’ classroom ready ahead of what was often quite physically involving, and find out how many bookings had already been made for conversation lessons.

The children’s lessons – different classes for different age groups and ability levels – often went by in a flash, with fairly short breaks in between. On a good day, this would all happen smoothly and everybody had a good time, but on a bad day, the material might be harder to convey and there might be unruly children to deal with. This could be especially challenging since in this job, I was expected to avoid using Japanese.

On most days, adults’ classes would follow after kids’ classes, and many of these were bookable conversation lessons that go on for under an hour each. Personally, I tended to find these classes more manageable, and having interesting conversations and/or seeing students’ progress often felt quite rewarding. Once the final slot was finished, I would normally have a short time before I could clock out and leave at night.

My experience as an ALT (assistant language teacher)

At the end of two years of Eikaiwa teaching, I looked for a new job and ended up working as an ALT for a dispatch company. The pay didn’t work out as well as in my previous job – as dispatch ALTs normally make less money than a JET or direct-hire ALT – but I had more sensible hours, weekends off, and more holiday time in general.

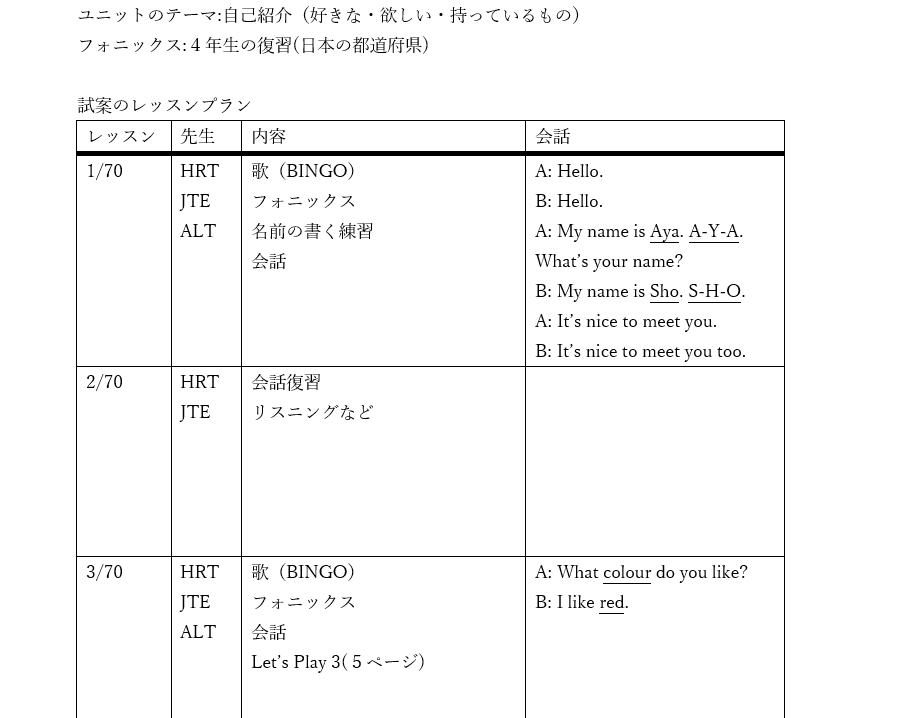

My week was divided between two elementary schools in northern Osaka Prefecture. In my first year of the job, I also had one day a week at one of five different kindergartens. I had this job during a transitionary period where elementary school textbooks were being replaced and schools were beginning to assign the role of “English Leader” to one of their regular teaching staff to focus on organising the English curriculum. Because of this, my experience varied depending on the school, but in theory, the setup should be more consistent across schools now that the system is in place.

In the elementary schools, I was sometimes asked to act as the main teacher during English lessons, while at other times I would have a smaller role. Lesson planning varied in the same way: at some schools, I would plan all the lessons for the classes I taught, but in others, the English Leader would organise everything and come to me for advice. At kindergartens, where the lessons were infrequent, I would always have a short meeting with the class teachers to decide on the next lesson material, as the national English curriculum only starts at third grade of elementary school.

My working day as an ALT was a little longer than it was as an Eikaiwa teacher, but I would normally know my schedule ahead of time, and there was a vague guideline of setting no more than four lessons for me to attend in a day. At kindergartens, the lessons were very short and would sometimes all be done by lunchtime. There were also a few days in the year where there were school events such as the sports day. On these days I had no classes and would usually find some way to help the other teachers.

An average day as an ALT

Most of my days as an ALT were at elementary schools. I would arrive by 8:30 in the morning, when there was often a meeting for all staff in the staff room. At most schools, I had a desk assigned to me, so I would sit there and prepare for my day. Sometimes I would have to get ready very quickly for my first lesson, but especially when I had a say in the schedule, I tried to avoid having first-period classes.

At Japanese elementary schools, most lessons are taught in a class’s homeroom, except for a few practical classes like home economics. I would go to each classroom in time to set up for the lesson, which would then take 45 minutes – though there were times when the homeroom teacher needed to take extra time at the beginning or end of the period to make announcements and so on.

From my experience of Eikaiwa teaching, I tended towards delivering lessons all in English, but I often prepared visuals using Japanese. The official textbooks used for classes from 3rd to 6th grade and the electronic materials that came with them also had Japanese instructions. In classes where I was a supporting teacher, most of the instruction was in Japanese, but I would normally still speak to the students in English.

Unlike at my Eikaiwa job, I often had work to do in planning and preparing for lessons as an ALT. I also had meetings with English Leaders and homeroom teachers, especially earlier in the school year. As this was a normal Japanese place of work, compared with the more foreign environment of an Eikaiwa school, it was useful that I could speak Japanese with the other staff. Other aspects that were quite unlike the Eikaiwa experience included school lunches, and being the last to arrive and first to leave. My day would normally end around 4:00, while salaried teachers would stick around to deal with all kinds of other duties.

Private teaching

One other type of English teaching worth mentioning is private teaching. There are sites that let you post an advert for your teaching services, and interested students will contact you to arrange lessons. You can set your own rate, and the amount you can make per hour is generally a lot better than other teaching jobs, but it’s probably only realistic to do this as a side gig while having a different full- or part-time job.

Later in my time in Japan, I taught a few regular private lessons. These were usually one-on-one, and we would meet in a café or other public place. My students ranged from high school students to various professionals, and it was often quite fun to have free rein to decide on what to talk to them about. However, since I always had a full-time job, it wasn’t easy to have more than two or three regular students at a time.

For private teaching, I think that having Japanese knowledge is definitely valuable, as it makes it easier for students to contact you, especially if they feel nervous about starting lessons.

Is English teaching for you?

There are a lot of differences between the various kinds of English teaching jobs – and these are definitely not all of them! When you’re thinking about looking for an English teaching job in the Osaka area or anywhere in Japan, you need to consider issues like pay, hours, holiday time, location and, particularly if you’re applying from outside Japan, whether the employer can sponsor your visa. This article has some useful advice on these details.

In my opinion, English teaching can be a lot of fun, and the Osaka area is a great place to do it, with convenient transport and a great atmosphere. If you want to experience more of local culture and customs, then an ALT job might suit you best, but Eikaiwa teaching can be a good option if your main interest is the teaching itself. And finally, if you’d prefer not to be an English teacher, remember that there are other ways to find work in Osaka too.

Except where otherwise noted, graphics are by Rachel Stewart and other images are photographs taken by the author.