Table of Contents

Edo Period People Crazier About True Crime Than Us?

Bunraku

Japan was stunned earlier this year when the famed kabuki actor Ennosuke Ichikawa IV (b. 1975) allegedly attempted a group suicide with his mother and father. The latter had also been a top kabuki actor, as is often the case in that hereditary all-male milieu. The parents died, while Ennosuke was hospitalized for over a month. He has since stated that they all made a pact to leave this world and be reborn together in the next, after learning of an upcoming weekly magazine scoop about Ennosuke’s alleged sexual misconduct toward fellow actors.

Sensational stuff. Imagine that less than a month later, a feature film based on the incident opened in theaters, becoming the blockbuster of the year and popularizing a whole new genre. Today, it usually takes a few years for a true-crime tale to get a cinematic treatment, and the resulting movies aren’t often Star Wars-level sensations. It seems things were different in 1703, when Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s bunraku play The Love Suicides at Sonezaki was staged before rapt audiences just four weeks after the events that inspired it.

Masters of Puppets

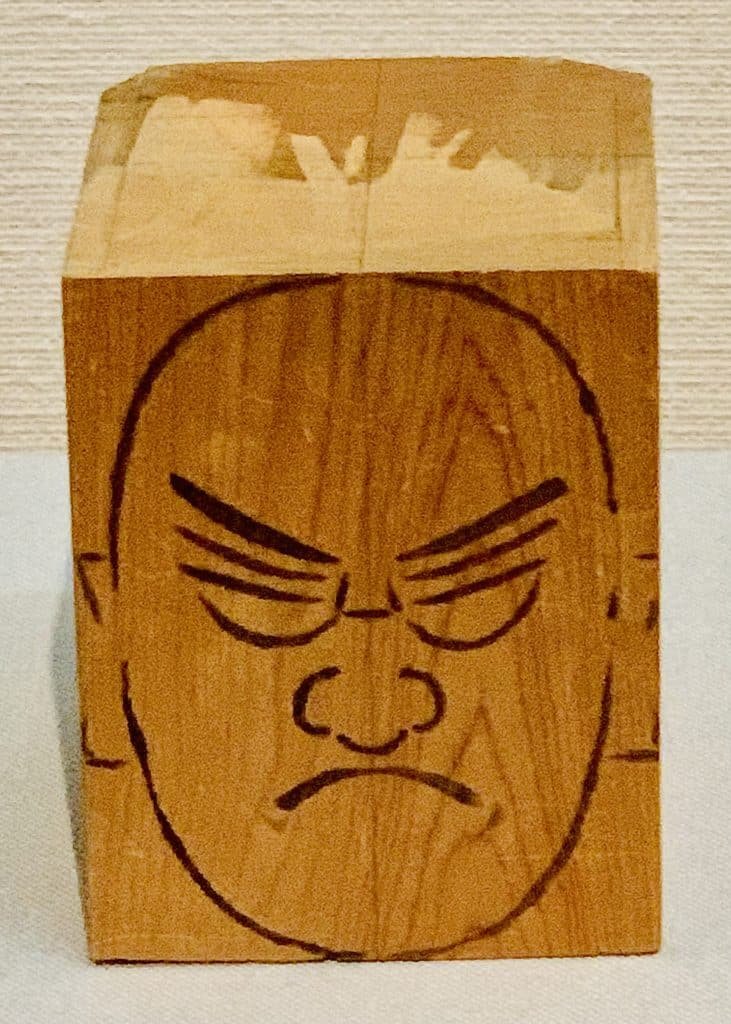

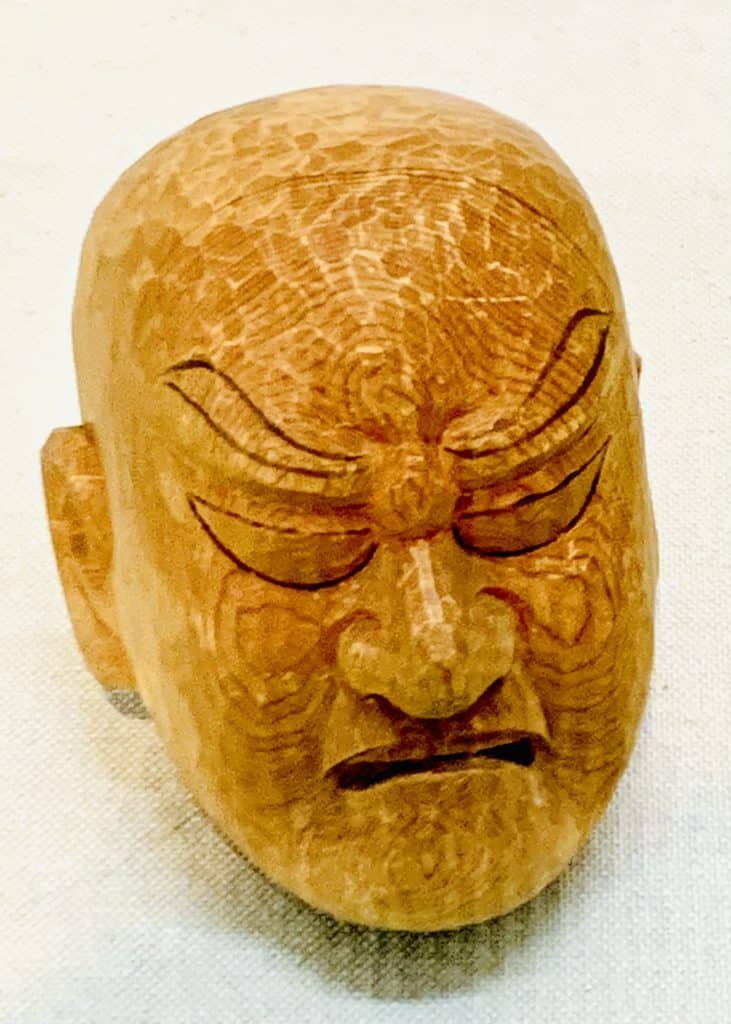

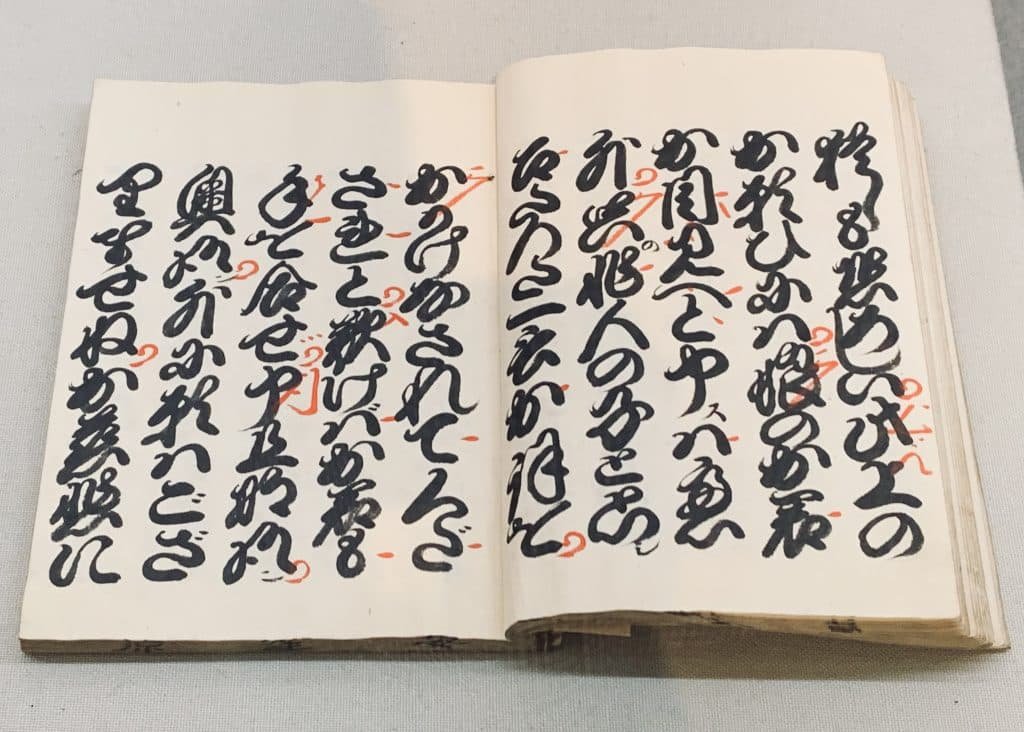

So, what is bunraku? It’s “traditional Japanese puppet theater,” which sounds fun and lighthearted, and there are indeed comic moments, but classics of the genre are mostly tragedies or (tragic) historical plays. It was originally called ningyo joruri, combining the words for “doll [puppet]” and “recitation with musical accompaniment.” The recitation is part spoken and part sung or chanted, with voices and emotional timbres rapidly changing as a single reciter (tayu) plays multiple roles, for example switching back and forth between a girlish falsetto and a baritone growl. In 1684 the Osakan reciter known as Takemoto Gidayu founded the Takemoto-za theater in Dotonbori, where a fusion of joruri recitations and plays staged with puppets caught on with the public, and those penned by Chikamatsu made it a pop-culture phenomenon. The term bunraku was later derived from Bunraku-za, a popular theater in 19th-century Osaka, in much the same way that house music is said to have taken its name from the Chicago club the Warehouse. While we’re talking etymology, joruri [lit. “pure lapis lazuli”] derived its name from one especially popular 15th-century tale, Joruri-hime Monogatari [The Tale of Princess Joruri], which was – you guessed it – a tragic love story.

Joruri consists of one man with a voice and another with a plucked string instrument, originally a lute-like biwa, later a twangy three-stringed shamisen, which remains the standard today. The ningyo joruri revolution came when puppeteers began silently acting out epic tales with articulated dolls on elaborate sets. The puppets were initially small and handled by one person, but today they are about a meter high and important characters are manipulated by three puppeteers, one for the feet, one for the left hand (or right hand, as seen by the audience), and one for the head. Originally all puppeteers were dressed in black and shrouded in featureless black hoods, minimizing their presence even as they remained clearly in view, but today at important venues like the National Bunraku Theater[CS1] near Nipponbashi station in Osaka, the head-handling honchos have their faces exposed, perhaps because of public demand to see the stars. This only adds to the central magic of the genre, which is that despite all its machinery being in plain sight, from the men behind the puppets to the reciter and accompanist on a platform to the side of the stage, after a few minutes you forget the artifice, ignore the flesh-and-blood humans, and are completely sucked into the world of moving dolls.

[CS1] National Bunraku Theatre

This is thanks in large part to the incredibly fluid, lifelike and emotive movements of the puppets. Traditional arts and crafts in Japan often take decades of training, and here too it’s said that it takes ten years to become a leg operator (hunching down unseen by the audience and literally the low man on the totem pole), ten more to manipulate an arm, another ten to do the head, and yet another decade to be the head-master for a principal character. This means the big-name puppeteers tend to be guys of a certain age, as do the star reciters, many of them venerable Living National Treasures. This makes it all the more amazing when they join forces to bring a character like the young courtesan Ohatsu (one of the two main characters in The Love Suicides at Sonezaki) to life.

Love Suicides Sites: Sketchy Sennichimae, Northern (Red) Lights

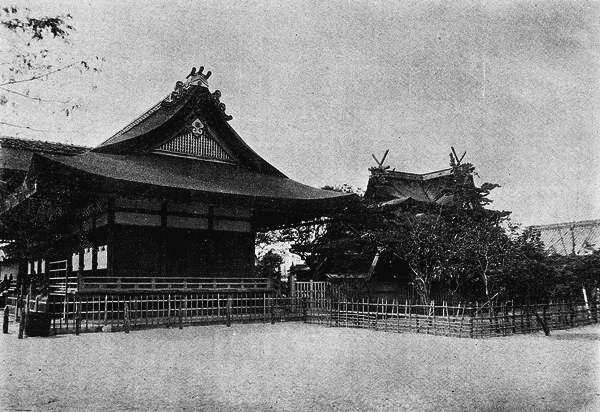

The National Bunraku Theater stands on the north side of Sennichimae-dori, east of Namba between Sakai-suji and Matsuyamachi-suji. It’s a colorful and slightly seedy area today, and was so historically, with red-light districts, cemeteries, and a public execution ground giving the Sennichimae area a less than wholesome character. Not far to the northwest is Dotonbori, where the aforementioned Takemoto-za and countless other theaters once drew crowds, and a block and a half down Sennichimae-dori to the east is Ikutama Shrine, where the story opens in The Love Suicides at Sonezaki.

Ikutama Shrine, near the Tanimachi 9-chome subway station, is a large Shinto shrine with misty origins before recorded history. It’s the site of the Ikutama Festival, every July 11 and 12, which kicks off Osaka’s summer festival season. The shrine is surrounded by a kitschy love hotel district, one of the city’s largest (there’s a smaller and shabbier one behind the National Bunraku Theater), interspersed with many Buddhist temples. This odd mix of virtue and vice may stem from temples’ connection to death and the afterlife, as they sometimes make ends meet by offloading land formerly home to cemeteries––which not many reputable buyers or renters would want, but love hotels are happy to occupy. Love and death, side by side, bring us back to The Love Suicides at Sonezaki and its doomed couple.

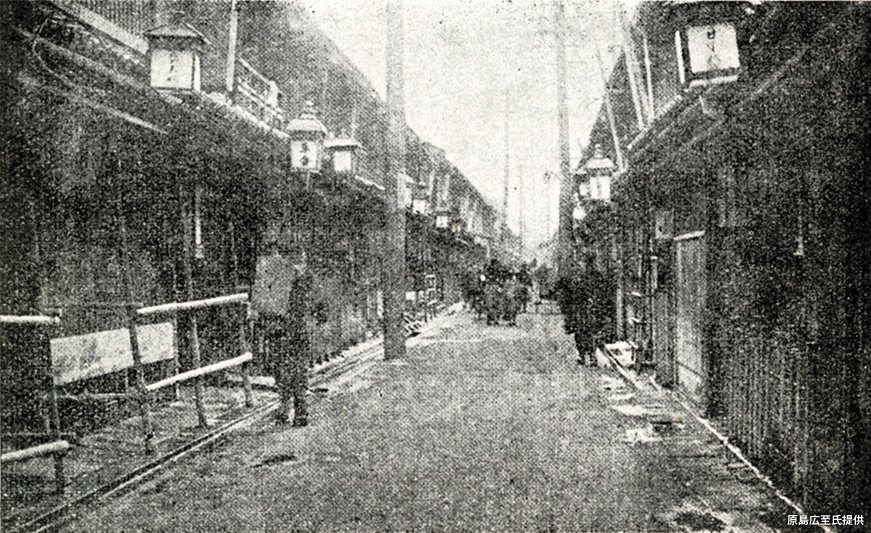

The true events that Chikamatsu so swiftly turned into a hit play occurred in the wee hours of April 7, 1703. Ohatsu (a pseudonym, with the honorific prefix o- added as was the custom for women in pre-modern times), a 21-year-old female sex worker employed at Tenma-ya in the Sonezaki-Shinchi red-light district, more or less overlapping with today’s Kitashinchi, lit. “north new land” (shinchi was often applied to red-light or entertainment districts, frequently built on reclaimed land or former wilderness), and 25-year-old Tokubei, a sales clerk apprenticed to a soy sauce merchant in Uchihonmachi, were found dead in a double suicide in the woods around Tsuyu-no-ten Shrine. We’ll return later to the shrine, known today as Ohatsu-Tenjin after the heroine, as that’s where the story comes to its tragic end. For now let’s return to the other shrine, Ikutama, where the action begins in the bunraku play. Leaving aside the question of how closely it’s based on real events, in the fictionalized version the two erstwhile lovers meet by chance at the shrine after not seeing each other for quite a while, just as Ohatsu is wrapping up a circuit of 33 Kannon (Buddhist goddess of mercy) temples and shrines in Osaka. The pilgrimage is portrayed in the play and foreshadows the “reborn together in the next life” theme of the climax, but that part is usually omitted from performances so as to get to the good stuff sooner. Bunraku, kabuki, noh… all traditional Japanese theater performances tended to be extremely long by present-day standards, like “bring your lunch to the theater, spend all day, take a nap during the slow parts” long, since life was more leisurely in old Japan and people lacked the vast range of entertainment options we enjoy today. If you go to see any of these today, you’ll usually see an abridged version… which may still seem long, but will be worth your while.

For a Few Dollars More…

Back to the story. When Ohatsu sees Tokubei, she’s none too pleased that he’s been out of touch for some time. He explains that his boss, who’s also his uncle, was impressed with his hard work and was trying to marry him off to his (the uncle’s) wife’s niece and have him take over the shop. Tokubei refused because of his devotion to Ohatsu, but the uncle went behind his back and gave betrothal money to Tokubei’s stepmother. When Tokubei put his foot down, the enraged uncle fired him, telling him to get the hell out of Osaka, that he’d never work in this town again, and what’s more he wanted his money back. Tokubei went to his stepmother’s village and managed to pry the betrothal money out of her, but then he ran into his friend the oil merchant Kuheiji, who begged him for a loan and promised to pay it back in three days, before the deadline for repaying Tokubei’s uncle. Tokubei agreed.

Parentally arranged marriages, with varying degrees of willingness on the part of the children, still occur in Japan. Betrothal money (paid by the groom’s family to the bride’s) still exists too, the going rate being about 1 million to 1.5 million yen according to a major wedding-industry company, as do dowries (paid by the bride’s side). It all seems pretty antiquated, and it’s far from the universal practice it was, even among working-class folks, in 1703. But whether then or now, loaning your money to a friend when you’re in dire straits yourself seems like sheer foolishness. It’s a horror-movie “don’t open that cellar door” moment for the audience, who can guess that Tokubei is never going to see the money again and it’ll all be downhill from there. Apologies to my friends, but I can’t think of a friend to whom I’d fork over the cash in that situation… but either it was a different time, when loaning money to a friend in need was a no-brainer, or Tokubei was particularly pure-hearted, or both.

Unlike the aristocratic Romeo and Juliet, these star-crossed lovers are a working-class guy and a working girl. Fittingly for a story set in mercantile Osaka, their troubles revolve around a few pieces of silver. While they’re at Ikutama Shrine, who shows up but his “friend” Kuheiji… who denies having borrowed the money, denounces the IOU that Tokubei produces as a forgery and Tokubei’s request as extortion, and to add insult to injury (or injury to insult), has his cronies beat him up. End of scene one.

There’s a Place for Us

Things get no better in scene two at Tenma-ya, where Ohatsu is the most popular of the young ladies on staff. Tokubei is outside the place and she has slipped out to speak with him when the dastardly Kuheiji appears and starts conversing with her co-workers. Tokubei hides beneath her kimono (one advantage of garments of that time that we don’t have today) as she goes inside to join the conversation. Kuheiji talks up the “extortion attempt” and predicts that Tokubei will be executed for it. Under the kimono, the two lovers communicate with their hands and feet, and he conveys his will to die by drawing her ankle across his throat. Quite a “feat” of communication… [Sorry!!] Scene two ends with the two slipping out to meet their doom.

The climax takes place in the Wood of Tenjin near Tsuyu-no-ten Shrine. The shrine still has that official name today, though everyone calls it Ohatsu-Tenjin (also the name of the neighboring shopping arcade, a main artery on the east side of Umeda), and it’s now a “power spot” for couples and home to some artworks of questionable taste (see photos). It’s close to Tenma-ya, which was a real place, near what is today Hanshin Fukushima Station. The couple finds a pine tree with entwined branches that looks like just the spot to depart for the afterworld, and after hesitation on his part and encouragement on hers, he kills her and then turns his dagger on himself. Oh, the humanity! You could indeed get the death penalty for a fairly petty crime in those days, but surely they could have fled Osaka and gotten a fresh start elsewhere, or something… Here, the genuine belief that they would be reborn together in a better place is essential. It may have been something similar that spurred well over a dozen couples to their own double deaths in the wake of the bunraku and kabuki adaptations of the incident, a phenomenon similar to the copycat suicides in Europe following publication of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther some decades later. What was it about the 18th century? In various parts of Europe, authorities banned the book and/or outfits resembling its protagonist’s, and in Japan, the Tokugawa shogunate first banned shinju-mono (plays, etc. about love suicides) in 1722, then outlawed love suicides themselves the following year, and even forbade use of the word for them, shinju (written with the kanji for “heart” and “center”), for beautifying the act. How could they penalize the dead? For one thing, their corpses were refused burial and left to rot, and if one or both should happen to survive, the consequences were not pretty.

Suicide Solution

This cramped the style of Chikamatsu Monzaemon, whose plays in the genre turbocharged his career and put bunraku on the map. The Love Suicides at Sonezaki was Chikamatsu’s breakthrough work and remains a well-loved classic, thanks in part to its connections with well-known local sites. His The Love Suicides at Amijima (1720), based on the true story of the double suicide in Amijima, near Kyobashi in present-day Miyakojima Ward, of a paper merchant and a Sonezaki-Shinchi courtesan (do we detect a pattern here?) is actually considered a much superior masterpiece. In his time he was better known for historical plays, and his dramatization of the famous tale of the 47 ronin (masterless samurai), who avenged their lord after he was forced to commit seppuku, then committed seppuku themselves, was the basis for the bunraku play The Treasury of Loyal Retainers, a favorite to this day. Everyone loves a suicide story! After the ban on shinju, Chikamatsu turned elsewhere for dramatic material, but he was 70 at the time and died a few years later. His grave is down a narrow alley between an apartment building and a gas station on Tanimachi-suji, between Tanimachi 6-chome and Tanimachi 9-chome not far from Ikutama Shrine, the temple housing his family plot having been relocated.

When Westerners think of puppets, they tend to think of children’s television, old-fashioned street entertainment, and manic comedy vibes. But in various Asian countries there are more serious and sophisticated dramatic puppetry traditions, as UNESCO recognized in 2003 when it designated both bunraku and wayang (Indonesian shadow puppetry) as World Intangible Cultural Heritage. Among traditional Japanese performing arts, bunraku is as complex, entertaining, and entrancing as kabuki or noh. The place to see bunraku in Osaka is the National Bunraku Theater, where condensed versions of famous plays are regularly staged. The condensed digests are still around three hours, so be ready to watch something as long as one of the lengthier Hollywood movies so common these days. Be sure to rent an audio guide no matter how proficient your Japanese might be (I think this goes for native speakers as well), since the language is antique and stylized. And be prepared to cast aside preconceptions and be astounded at puppets that come to life in stories all the more tragic when they’re (at least partly) true.