Green tea is among Japan’s most famous products. One of the representative forms of Japanese green tea is matcha, which is popular today as an ingredient in milky drinks and desserts, as well as being central to the tradition of tea ceremony. Tea ceremony as we know it now owes a lot to the innovations of one man, the 16th-century tea master Sen no Rikyu. As one of Sakai City’s most significant historical figures, he continues to be celebrated today for his contributions to Japanese culture.

This article will take a look at Sen no Rikyu’s life, his lasting impact on tea ceremony, and where you can follow in his footsteps in the Osaka area today.

Table of Contents

The life of Sen no Rikyu

Sen no Rikyu was born in 1522 and was the son of a successful fish merchant in Sakai. 16th-century Japan was in the middle of an era of ongoing civil war called the Sengoku (“warring states”) Period. Nobody held real authority over the country, while clans and local samurai lords controlled their individual provinces and domains. Sakai, situated right on the boundary between the provinces of Settsu, Kawachi and Izumi, was an unusual case. It was a commercial city governed by a council of merchants, and traded with many clans without being controlled by any. This freedom from influence also helped it become a major port for international trade, making it remarkably cosmopolitan for 16th-century Japan.

As a young man in Sakai, Rikyu studied tea ceremony under Kitamuki Dochin and Takeno Jo-o. He later underwent training at the Zen Buddhist temple of Daitokuji in Kyoto. We know little about the details of his life until later in the 16th century, when political turmoil grew further and Rikyu had his chance to become the tea master he is known as today.

In the 1560s, the powerful warlord Oda Nobunaga began the process of reunifying Japan by defeating his rivals. In the process, he gained control over Sakai, where he had previously purchased firearms, and used it as a base for his exploits in the area. He also became interested in tea, and took on Sen no Rikyu as one of his personal tea masters in the 1570s. Rikyu and other merchant tea masters became politically influential under Nobunaga, even performing secretarial tasks for the warlord.

Nobunaga’s reign was short-lived, as he died after being betrayed by one of his generals in 1582. This did not spell the end of Rikyu’s influence, though, with Nobunaga’s retainer Toyotomi Hideyoshi soon taking over his late master’s position. Hideyoshi got even closer than Nobunaga to exercising authority over all of Japan and, importantly, he was even more passionate about tea.

As Hideyoshi’s close friend and advisor, Rikyu’s political rise accelerated. In addition to his official functions in art and culture, Rikyu was important to Hideyoshi’s diplomatic efforts. Rikyu communicated with influential figures, enabled political meetings, and may even have been left in charge of Osaka Castle – built on Hideyoshi’s orders – while his master was away. However, as an unofficial advisor, Rikyu’s position was also precarious. In 1591, he was suddenly banished back to Sakai from Kyoto, which was then the formal capital of Japan, only to be quickly ordered to return and then perform ritual suicide. The exact cause is still unknown, but it is likely that some combination of personal disagreements and political developments caused Hideyoshi’s abrupt change of attitude.

Sen no Rikyu’s mortuary temple is part of Daitokuji in Kyoto, as is the mortuary temple of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s master Oda Nobunaga. Hideyoshi is said to have later regretted ordering Rikyu to death.

Japanese tea culture before Rikyu

Tea was probably first introduced to Japan from China during the 8th century, but it took some time before it was widely popularised. The monk Eisai, also known for founding one of the main branches of Zen Buddhism, is often credited with kickstarting tea culture in Japan by bringing back tea seeds from China for cultivation in the 12th century. Eisai also introduced the method of brewing powdered tea known as matcha,and as the first in Japan to write about tea, he promoted it for medicinal use. Both matcha and Zen soon became popular among the samurai class.

Depending on one’s place in society, mediaeval tea culture varied. Monks would drink tea as a ritual practice to aid their meditation. Meanwhile, teahouses opened near Buddhist temples, allowing tea drinking to spread among the general population too. On the other hand, lavish tea parties were in vogue among samurai, who would compare their knowledge of tea in competitions and show off teaware and other luxury goods imported from China.

Over time, these parties became more subdued, as people like the 15th-century military leader Ashikaga Yoshimasa and the tea master Murata Shuko preferred a more muted aesthetic. This involved deprioritising the use of Chinese teaware and formalising the process in general. This later style directly influenced Sen no Rikyu, whose master Takeno Jo-o followed in Murata’s footsteps.

Rikyu’s tea ceremony

Sen no Rikyu’s tea ceremony was in the wabi-cha style associated with Murata Shuko. This approach emphasised the wabi aesthetic of rustic simplicity, by using everyday teaware made by local craftsmen. Rikyu applied this same philosophy to every aspect of tea ceremony, introducing new tools and even redesigning the teahouses themselves.

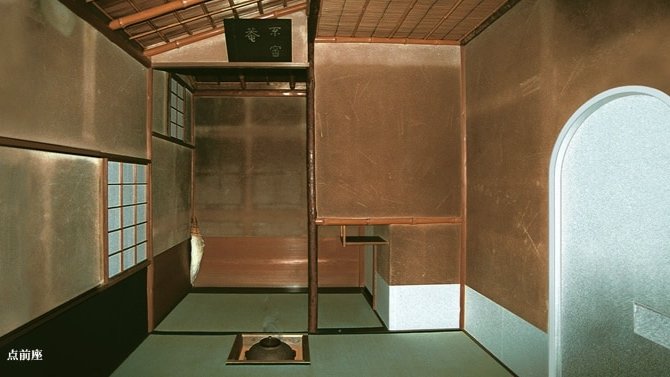

Rikyu’s predecessors preferred small teahouses to the large halls used in earlier samurai tea parties, but Rikyu took this further, even designing rooms as small as two tatami mats. The only decorations were in the tokonoma, a small alcove displaying a piece of calligraphy and a simple flower arrangement. He also placed new importance on the garden leading to the teahouse, making it an important part of the overall experience.

Another of Rikyu’s innovations was the nijiriguchi, a tiny square door for entering the teahouse. The design forced guests to enter humbly, on their hands and knees, and prevented them from concealing swords. As a result, all guests in this kind of teahouse were in the same position, regardless of their social status.

The cramped rooms may sound uncomfortable, but hospitality was also a key element of Rikyu’s tea ceremony. Guests would enjoy each element one by one: the decorations, a small meal, a sweet, the careful process of the tea’s preparation, and finally the tea itself. Many of these steps have since become extremely formalised, but initially the goal was to produce a comfortable atmosphere, free from serious matters.

The matcha would be presented to guests in a characteristic hand-shaped tea bowl. Today, the matcha offered is usually what is called usu-cha, meaning “thin tea”. Given that matcha is quite strong-tasting, it might seem surprising that this is regarded as “thin”, but formal ceremonies in Rikyu’s time involved the preparation of the even stronger koi-cha, “thick tea”. This is made with far more matcha powder and is so intense in flavour that guests are expected to share a single bowl between them.

As much as Rikyu’s philosophy favoured treating all guests the same and avoiding weighty discussion, the reality was often quite different. After all, the biggest fans of his tea ceremony style were samurai lords who would use these events for political purposes. Toyotomi Hideyoshi was known as a more diplomatic leader than his often brutal predecessor Oda Nobunaga, and inviting important people for tea ceremonies played an important role in establishing his legitimacy. It is possible that this – together with Hideyoshi’s non-wabi taste for extravagance as seen in his famous Golden Tea Room – contributed to the rift between him and Rikyu.

Rikyu’s advancement of the wabi-cha style and his own innovations resulted in something quite different from earlier tea parties. “Ceremony” is a much more fitting description for Rikyu’s approach, which soon spread among the samurai elite and set the tone for the tea ceremony tradition ever since.

Rikyu’s lasting influence

Many other people were inspired by Sen no Rikyu and his tea ceremony approach. He had several disciples, such as Yamanoue Soji, a merchant from Sakai. Yamanoue is known for writing about Rikyu and tea ceremony of that era. In his writings, he also explained ichi-go ichi-e, a concept associated with Rikyu and other wabi-cha practitioners, which advocates treating every moment as a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Like Rikyu, he fell foul of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and was executed a year before Rikyu’s own death.

The samurai lord Furuta Shigenari – also called Furuta Oribe – was another famous disciple. He succeeded Rikyu as Hideyoshi’s tea master, and established his own tea ceremony style in his domain in central Japan. Oribe ware, a distinctive pottery style in Gifu, is named after him. He also suffered a harsh fate: Tokugawa Ieyasu, who would eventually complete Nobunaga and Hideyoshi’s mission of reuniting Japan, accused him of a secret plot and sentenced him to death.

Another samurai disciple was Hosokawa Tadaoki – also called Hosokawa Sansai. Under Hideyoshi, he helped promote tea culture alongside Rikyu, and he wrote several books on the subject. He became an important tea master too and went on to develop the Sansai school of tea ceremony. Unlike Furuta Oribe, he supported Ieyasu, and ended up being richly rewarded for his military contributions.

Rikyu’s own descendants also carried on his work after his death. Three of his great-grandsons, Soshitsu, Sosa and Soshu, took on the role of carrying on his legacy. They each founded a school of tea ceremony with names based on their relative locations in Kyoto: Urasenke, Omotesenke and Mushakojisenke, respectively. Since then, many other tea ceremony schools around Japan branched off from one of these three, and continued the work of passing on Rikyu’s philosophy and methods. Most tea ceremony practised today continues to observe the wabi-cha style as promoted by Rikyu and the schools that followed him.

Experiencing tea culture today

Visitors can go to various places today to learn about Sen no Rikyu and experience tea ceremony, especially locations with a historical connection to the man himself, such as Sakai and Kyoto.

In Sakai is the Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko, which is near Shukuin station on the Hankai tramway. This museum celebrates Rikyu and another famous person from Sakai, the author Yosano Akiko. There are exhibits on both historical figures, with Rikyu’s section featuring information on his life, various tea artifacts and a full-sized reproduction of Tai-an, the last remaining teahouse to have been designed by Rikyu. You can taste matcha and traditional sweets, and there is even an option to reserve a lesson in performing tea ceremony, taught by masters of the Urasenke, Omotesenke or Mushakojisenke schools. Near the museum, you can also find the former site of Rikyu’s home, and a traditional confectioner’s shop called Honke Kojima which has existed since Rikyu’s time.

Other tea destinations in Sakai include Daisen Park. Among Daisen Park’s facilities is an elegant Japanese garden, which has matcha and sweets available for visitors. The park also features two connected teahouses called Shin-an and Obai-an, which are formally recognised as tangible cultural properties of Japan. Only Shin-an is open for guests to enter and buy tea. Daisen Park is close to Mozu station on the JR Hanwa line.

Daisen Park is one of two locations used for tea ceremonies during the annual Sakai Festival. The other is Nanshuji, a Buddhist temple with a tea house that Rikyu once frequented. Nanshuji is a little south of the Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko. Elsewhere in Sakai, near Sakaihigashi Station on the Nankai Koya line, the confectioner’s shop Kokyuan has a recreation of a teahouse that once stood at Rikyu’s residence near Osaka Castle.

Besides Sakai, Osaka Castle features a replica of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Golden Tea Room, while Zuihoji Park in Arima Onsen and Kitano Tenmangu in Kyoto hold events commemorating Hideyoshi and Rikyu’s famous tea parties. Kyoto is also home to Daitokuji, the temple most strongly associated with Rikyu, and in the south of Kyoto Prefecture is the original Tai-an teahouse. These offer many more options beyond Sakai for visitors to follow in the tea master’s footsteps.

Except where otherwise noted, images are photographs taken by the author.

A nice write-up!

Although there is very little to see at the site of Sen-no-Rikyu’s former home in Sakai, there is a small well in one corner. This was built using wood removed from one of Daitoku-ji’s gates during a renovation since the gate was originally built thanks to donations from Sen-no-Rikyu.

Thank you Gary! I didn’t end up saying very much about Rikyu’s old home in this article, but those are some interesting little details.

[…] key figure in the history of the Japanese tea ceremony is Sen-no-Rikyu, who lived from 1522 to 1591. Due to his influence, the Japanese tea ceremony gradually shed […]