Table of Contents

So You Want To Try Sake?

You’re in Osaka and you’ve got your list of things you want to do, places you want to go and, of course, food you want to eat. And as part of any culinary experience in Japan you probably also plan on including a sake tasting somewhere along the line. And why wouldn’t you?

In my admittedly biased opinion, sake is the most versatile alcoholic beverage out there. On average, it sits around 15% -16% alcohol – not much more than wine and significantly less than spirits and many liqueurs. Sake has anywhere from 1/10 to 1/3 the acidity of wine, depending on the wine and the sake. It contains no preservatives and can be sweet or dry or anywhere in between. Sake can be young, old, fizzy, still, clear, cloudy, heavy, light, dry or sweet; it doesn’t matter what you’re into, sake has you covered.

Perhaps you’ve tried sake in your home country or perhaps it’s your first time. Either way, delving into sake can be a little daunting for some, but trust me it’s a rabbit hole worth going down.

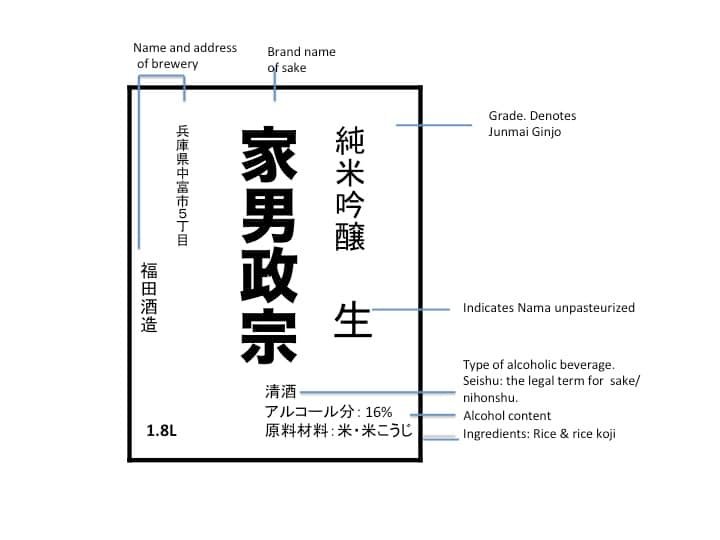

Of course one of the biggest hurdles for becoming familiar with sake is trying to make sense of the labels. Some of the terminology can be confusing, even for native Japanese speakers, so it’s helpful to have a bit of an idea of what you’re looking for when you order sake in a restaurant. So, with that in mind let’s take a little crash course in navigating sake and its mysterious labels so you can get the most out of your sake experience.

Firstly, what is sake? Technically sake is called nihonshu or seishu in Japanese. The word “sake” is often used as a blanket term for alcohol in general, so sometimes it’s advisable to specify that you’re looking for nihonshu when you are dining out or in a liquor store. Nihonshu differs from other Japanese liquors such as shochu or awamori in that it is not distilled (like gin, vodka, whiskey, tequila etc.)

Nihonshu is essentially brewed in a process much closer to (but still quite different from) beer, than spirits or wine. Speaking of which, you can call it sake, nihonshu or seishu, but for the love of all good things, don’t call it “rice wine”. It’s just plain wrong. Anyhow, I digress.

One of the things that can be surprising for visitors to Osaka and Japan is that sake is not quite as ubiquitous as you might think. Sure, it’s not exactly difficult to find, but it’s not always a given that sake will be on the menu. And even when it is, it’s often the case that the restaurant has simply grabbed one or two of the easy to find, big name labels without much thought going into the selection.

One solution is seeking out nihonshu specialty bars or restaurants, but even then you are subject to the prejudices and tastes of the proprietor of that particular venue. You might not realize what you’re missing out on. What you really want to do is try the spectrum of sake. And it is quite a spectrum. But before we get into where to go, let’s look at what sake is – and what it isn’t.

What Is Sake?

We won’t go into too much technical detail of exactly how nihonshu is produced, but put simply, it is a beverage primarily made from rice, koji, water and yeast. Koji? Yes, koji is the magic ingredient; a fungus mold that is propagated onto rice to convert starch into sugars (that are non-existent in rice) essential for the process of fermenting glucose into alcohol. Koji is also found in the production of soy sauce, miso and is used in many Japanese dishes.

In the early stages of production, one of the first steps is to mill the rice. This is where the outer layers of rice are slowly ground away to remove fats and proteins and get closer to the starchy center of the rice, which is where the koji does its magic.

Now, stay with me, all this is relevant to our cause.

Next, rice is washed, soaked and then steamed. This is then added to a starter mix with water, yeast some of that koji rice that we mentioned earlier and more steamed rice. This mash is then increased by additions of rice and water as the fermentation process continues. It is then left to ferment for a further twenty to thirty days or so. Finally, the finished sake is then pressed, filtered, pasteurized, cut with water (to slightly reduce the alcohol content), bottled, pasteurized once more and shipped out. Now, depending on the style of the sake some of these steps may be skipped and knowing this will help us decipher the labels.

Remember I mentioned how the rice is milled in the early stages? Well, most nihonshu is actually “graded” by the amount that is milled away (there are other factors involved, but this is all we need to know for now).

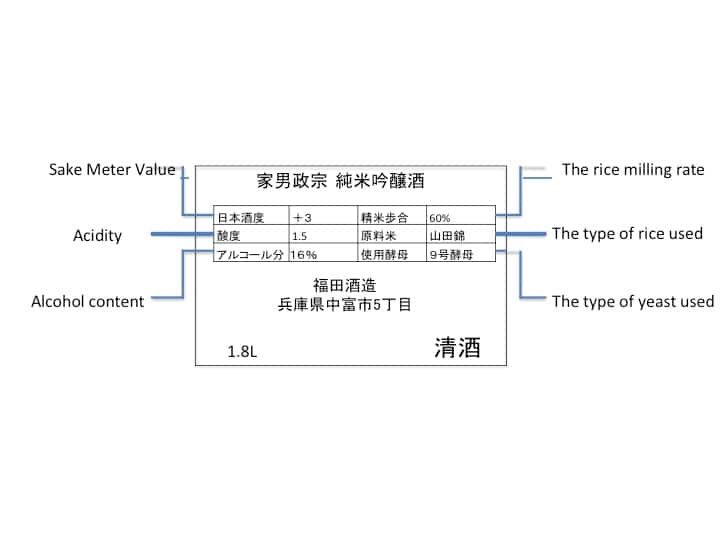

This milling rate is called the seimai buai 精米歩 and it will be listed on the back label of a bottle of premium sake. So what does it mean? Put simply, it will serve as an indication of how light or heavy the sake may be. The number indicated on the label is the percentage of the rice grain that remains after milling. In other words, if it says 30%, that means 70% of the outer layers of rice were milled away. Obviously the more that is milled away, the more expensive it gets because, among other factors, the brewer will need more rice.

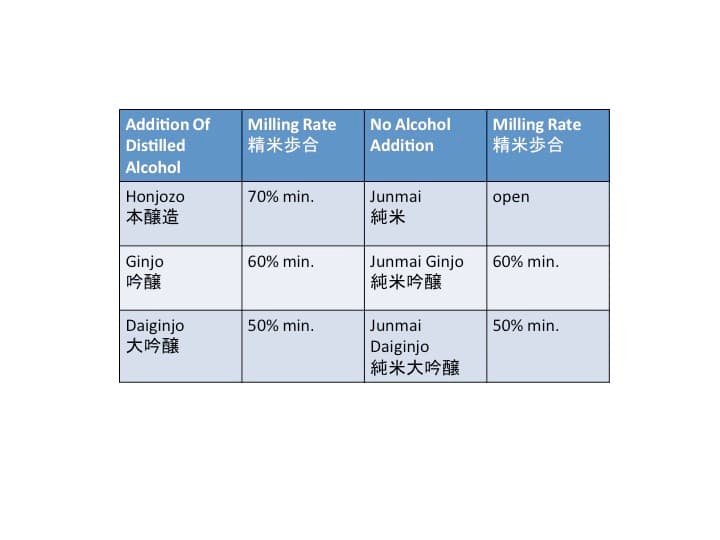

So now let’s take a look at some of these grades:

普通酒 futsu-shu

Like most alcohol, there is the cheap stuff and the good stuff. This is generally the cheap stuff. However, it’s not necessarily bad. In fact some of it is quite delicious and often be a good representation of what a brewery is really all about as it is usually the variety of sake that any given brewery has been brewing the longest. There is also a recent movement among some brewers that are shunning the grading system. If a brewery decides to sidestep the system, the sake is automatically lumped in the futsu-shu category. Bear in mind also this term is almost never on the label, but it may be listed on a menu or a shelf label in a retail store.

純米 junmai 本醸造 honjozo

Junmai means that there is no added alcohol ie. rice, water, yeast, koji and that’s it. If it’s a junmai it will almost definitely say so on the label. Junmai sake can use rice milled to any rate, but it’s usually around 70%. As we now start to split sake into two camps, we have junmai and honjozo (true brewed sake). Honjozo differs from junmai in that it contains an addition of brewer’s alcohol (usually made from sugar cane or molasses). This is added in the final stages of the production process to enhance aromas by dissolving some of the tasty bits of rice lees left in the final sake which would normally just be filtered out. In quality sake this is purely a technique used to enhance aromas and not a method for increasing alcohol content or increase yields like in some super-cheap futsu-shu.

Despite what some people might say, you cannot taste the added alcohol. It’s only added in very small amounts in a way that you might be able to detect the influence of the alcohol, but not the actual added alcohol itself. There are some people out there who think junmai is the be and end all. That’s fine, but adding alcohol is a valid brewing technique and at the end of day the sake made in this way tastes pretty damn good to me. Honestly, it’s also pretty difficult if not impossible to distinguish the two styles with 100% surefire accuracy.

Honjozo will often tend to be a little lighter and aromatic whereas junmai will be more full-bodied and earthy.

吟醸 ginjo 大吟醸 daiginjo

Ginjo is basically the premium end of sake (in terms of price). This is where sake gets a bit more refined, fruity, aromatic and elegant. It can be either junmai ginjo or just ginjo (which will indicate that alcohol has been added). The rice-milling rate must be a minimum of 60%. In other words at least 40% of all the rice grain must be milled away. Next up is daiginjo (ultra premium). This style requires the most hands-on care and attention to detail. Rice must be milled to at least 50%. Note that either of these styles can also be junmai if they do not contain any alcohol additions. These would be labeled as junmai ginjo 純米吟醸 or junmai daiginjo 純米大吟醸. If it doesn’t say junmai, it is aruten (alcohol added).

Other characteristics you might see

特別 tokubestu

This means ‘special’ in Japanese. You will see this prefixed to either junmai or honjozo as an indication that something extra or special has been done. This may be milling the rice more than is required for the grade or using a higher grade of rice or an unusual variety of rice or yeast strain. Basically it’s up to the brewery as to what makes it tokubetsu. It is not an indicator of flavor profile in any way.

生 nama

Most sake is pasteurized twice before leaving the brewery – once before storage and once after bottling. If either or both of these pasteurizing steps is omitted it may be labeled nama. Namazake is often fresh, lively and zippy. Incidentally you will also see this character used on menus as an indicator of fresh draft beer.

無濾過生原酒 muroka nama genshu

This one’s a mouthful. Muroka basically means the sake did not undergo fine filtering, a process which gives sake its clarity, but also strips elements of flavor and color. The nama refers to the sake being unpasterized (as above) and genshu means it has not been diluted with water. Most sake naturally ferments to around 20 percent alcohol by volume. This is then often diluted down to around 15 or 16 percent. So a muroka namagenshu will often (but not always) be a little punchy, robust and higher in alcohol.

にごり酒– nigorizake/cloudy sake

When the liquid sake is pressed from its chunky rice lees (called kasu in Japanese) sometimes brewers may leave some the sediment in the finished product giving a milky appearance and sometimes a thicker mouthfeel. Often on the sweet side.

山廃– yamahai

An old, traditional style of brewing technique where wild bacteria play a role in the early stages of the brewing process. Often funky and gamey in flavor

生酛– kimoto

Similar to yamahai, also using wild bacteria. Often high in acid and gamey.

Remember, these are all generalizations and, like anything, exceptions abound. There are a few more characters and stylistic indicators you may come across, but as a starting point to help you decide on buying a bottle of sake in a store or ordering in a bar, hopefully this will get you out of your sake pickle.

Another term you may see on a label or menu is:

日本酒度 nihonshudo (sake meter value)

This gives a scientific indicator of glucose density in the sake and therefore a rough indication of how dry or sweet the sake might be. Around +3 is average. Below +1 and into minus will indicate some level of sweetness. Above +8 will indicate a significantly drier style. Experiences may vary. Remember: Higher is drier.

Other details you may spot on a label, specifically the back label may include the rice and yeast variety used, serving temperature recommendations and sometimes acidity levels. Generally speaking, acidity levels are nothing to really concern yourself with. These are scientific measurements that are far more pertinent to the brewer than the drinker, but sometimes they’re there.

Some of the most common rice varieties are:

山田錦– Yamada nishiki

美山錦– Miyama nishiki

五百万石– Gohyakumangoku

雄町– Omachi

Where To Try Sake In Osaka

This has all been a lot of information to take in, but don’t worry, there’s no quiz at the end of all this. It’s just a way of getting our foot in the door so we know what we’re drinking. So now that we have some information, how can we use it? Like I said earlier, you could try a couple of glasses at a sake bar or maybe even a tasting flight of three or four to try and sample the variety of sake out there, but you would still only be barely scratching the surface. If you really want to sample some sake, head to the wonderful area of Tenma in north Osaka for a thorough sake experience.

There’s literally countless great places to drink in Tenma, but one place that really covers the possibilities of sake is, Sake to Cheese to Jiyu to Energy (to simply means “and”. Jiyu means “freedom”). Here, just a three minute walk from JR Tenma station, you’ll find anywhere from 60 to 90 varieties of sake from all over Japan of various styles that you can try at your own leisure and pace in a chic, relaxed space run by the affable, Papa.

A couple of things make “Energy” (it’s a long name, I usually refer to it as Energy) different from your average sake bar. Firstly, it’s not exactly a sake bar per se; it’s a tasting bar. For a set fee you can choose your time limit and taste as much sake as you like.

Time limits range from a quick 30minutes (not nearly enough time) for 1300yen, to a more reasonable 90 minutes for 2800yen. If you really want to settle in, 3500 yen for a full night. Another thing that makes Energy a little different is that you pour your sake yourself. That’s right. Once you’ve squared away with Papa what course you’d like to do, just grab a glass and head for the fridge. Here you’ll find three fridge doors full of sake, courteously arranged into seven categories:

Seasonal, small producers that focus on regionality, dry sake, modern/stylish, low-milled, mixed bag/variety, and popular superstar brands.

Note that within any of these categories you will find the various terminology and styles I mentioned earlier, so all you need to do is pick a shelf and try a sake. Remember it’s a tasting bar, not a drinking bar so only pour enough for a taste – about one or two fingers. Sit down, have a taste. Not your style? No problem, get back up and have a look for something else. Or perhaps try warming the sake. One of the beautiful things about sake is its versatility, and many sake, particularly ones that may show muted aromas or a rice-driven profile, will work wonderfully when they are warmed up. Papa is there to help you warm your sake up if it’s your first time, and he’ll also happily step in if you need any recommendations on kanzake (warm sake).

And it gets better. Let’s say you’ve tried a bunch of sake and now you’re feeling a little “palate fatigue”. You want to switch things up with a beer? No problem. Papa has some icy cold bottles of Corona or Sapporo beer in the fridge, which are also included in your fee. If you’re wondering about food (and you should because we all know it’s never wise to drink on an empty stomach) Energy only offers small cheese plates and maybe some nuts or nibbles. The good news is you can bring your own food! Being located in Tenma, you’ll be surrounded by a plethora of restaurants, and you’re free to get takeout from anywhere nearby.

I’m partial to a pizza from nearby Lavita Forno, or okonomiyaki from Bikkuri Okonomiyaki Marumi. Or maybe you’re on a budget and just want to bring some chips and snacks from the nearby 7-11, that’s fine too, it’s all up to you. There is even a microwave and toaster oven on hand to use at your convenience. Just remember it’s advisable to sort your food out before you start your timed session.

In most bars you’ll likely be served anywhere from 60ml to 120ml (or even more), which can inhibit the amount you can drink as intoxication creeps in before you’ve tried your fill. The main benefit of the tasting style at Energy is by keeping the servings reasonably small, you can cover more ground, try more styles and get a better feel for what’s out there and what kind of sake suits your palate.

Sake, nihonshu, seishu, whatever you want to call it, really is worth your time. The sheer variety of sake available is staggering and Osaka is as good a place as any to explore all that is out there. Once you’re armed with an experienced palate and some of the basic terminology to navigate the labels, you’ll be ready to hit the sake bars with confidence and on your way to becoming just as obsessed with sake as the rest of us.

酒とチーズと自由とEnergy

Osaka, Kita Ward, Tenjinbashi, 5 Chome−5−28, Ciel Blue, 2階

Open 5pm – 12am (Mon, Wed, Thur, Fri) 12pm – 12am (Sat) 2pm – 12am (Sun) Tues: CLOSED