Table of Contents

In the Shadow of the Castle

The Chuo in Chuo Ward means “central,” and it contains much of the old heart of Osaka, though it’s also the newest ward, formed in 1989 through a merger of the former Higashi (East) and Minami (South) wards. It would be easy to fill this article with descriptions of must-visit spots in Chuo Ward: Osaka Castle and the surrounding park, Shinsaibashi / Namba / Dotonbori, Amerika-mura (not a must-visit in my book, but listed as one in guides to Osaka), Kuromon Market, Midosuji Boulevard. But here at Osaka.com we never do things the easy way, so I will endeavor to dig into some of the ward’s more obscure sites. There’s no better place to start than the area around the preeminent symbol of this great city, and model for Chuo Ward’s yurukyara mascot Yumemaru-kun, namely Osaka Castle.

While the castle itself is a concrete replica of a 16th- to 17th-century fortress, built in 1931, there are turrets and stone fortifications dating back to the 1620s, including megaliths like the 108-ton Tako-ishi (Octopus Stone) and rocks inscribed with the crests of feudal lords. After the Tokugawa shogunate and the feudal system were abolished with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, a vast area around the castle was taken over by modern military facilities. Pre-World War II maps show a veritable Death Star of barracks, training grounds, shooting ranges, and the sprawling Osaka Arsenal, which churned out weapons and ammo from 1870 until it was destroyed in an air raid the very day before Japan’s World War II surrender.

The largest munitions factory complex in East Asia, it covered what is now the eastern half of the park, as well as OBP (Osaka Business Park) and the swath of land to the east of the castle now occupied by a JR railyard and the Morinomiya Danchi housing estate. The only arsenal building entirely remaining is the eerie, decrepit, yet scenic Osaka Arsenal Chemical Laboratory (built in 1919), which mysteriously is never torn down as virtually all crumbling prewar buildings have been, nor renovated and converted in the manner of other red-brick “retro buildings” (more on those later) around Japan. Why not, with a lovely neo-Renaissance structure and prime location? Craft beer brewery, anyone? Café? Art gallery? Its state of limbo may relate to its murky past as a chemical weapon synthesis and testing site.

As you wander through Osaka Castle Park, brick construction is your indication of remnants of the military-industrial complex. Right next to the castle is the former headquarters of the Japanese Imperial Army’s Fourth Division, now a tourist-oriented multipurpose facility called Miraiza. If you have an interest in figures – plastic representations large and small of characters ranging from Godzilla to sailor-suited anime girls – stop by the Kaiyodo Figure Museum in the basement. Scattered here and there throughout the park are red brick walls that hint at the atmosphere of the area before the bombing wiped it out.

All Downhill From Here

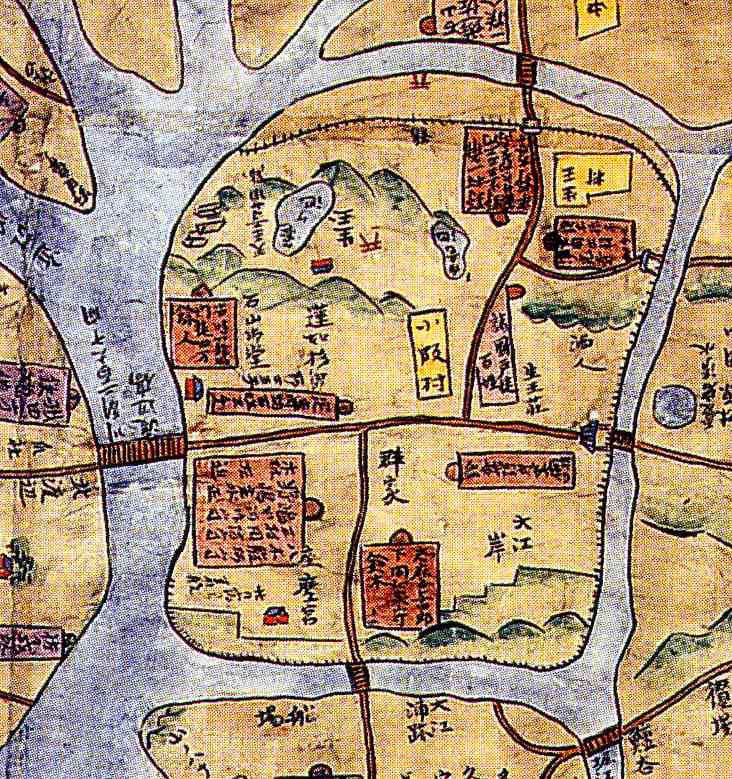

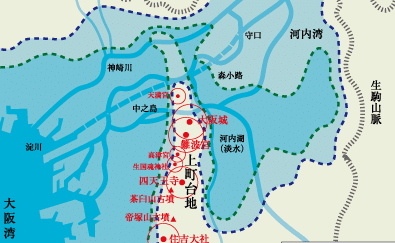

Before the militarization leading up to World War II, before the fall of Osaka Castle’s lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the bloody Siege of Osaka of 1614-1615, and before the castle was built, this was the site of the vast Ishigami Hongan-ji Temple. It began as a small hermitage that the Buddhist priest Rennyo, seeking solitude in chaotic times, built on a sleepy spit of rural land in a marsh along the Yodo River. He’s the source of the oldest written record of “Osaka,” a relatively new name for an area inhabited since prehistoric times. It first appears in writing in Rennyo’s 15th-century letter describing his location as something like “the large slope on the grounds of Ikutama Shrine [see this previous article] in the Higashinari district of Settsu province.”

When learning the meaning of the kanji for Osaka (大阪) for the first time, some wonder why an almost completely flat city is called “large slope.” It comes from this relatively hilly area of the city, which millennia ago was the only part of present-day central Osaka not underwater. Not so much big as long, the slope extends from what’s now Osaka Castle down to the Shitennoji Temple area and as far as Sumiyoshi Shrine. It’s known today as the Uemachi-daichi (Uemachi plateau), and running through Chuo Ward north to south, it’s the geographical and historical backbone of the city that grew around a formerly peaceful hamlet.

A block or two south of Osaka Castle Park is the more ancient Naniwanomiya Palace Site (home to the Emperor’s palace in the 7th and 8th centuries, when what was not yet known as Osaka was briefly the capital), which is now a large and wonderfully empty grassy expanse. Unlike the usual well-planned and manicured Japanese urban park, it’s almost nothing but grass and the occasional tree, with skeletal masonry replicating vestiges of the palace. As well as being a paradise for picnics, ball games, musical instrument practice, or whatever else calls for a wide-open space, it’s one of the last bastions of Osaka’s once-thriving unhoused community. Perhaps because the land is in a kind of legal gray zone, the city hasn’t moved to oust the inhabitants of some improvised dwellings in corners of the park. It’s a pale echo of the days (ended about 15 years ago) when most of Osaka’s parks and riversides were home to tents, hand-built shelters, improvised mini-houses and shanty-towns, in some cases with gardens, pets, and shoes placed neatly beside welcome mats.

Still Thriving: Karahori Shopping Arcade

Continue further south down the ridge of the Uemachi-daichi, along Uemachi-suji which runs down the west side of Osaka Castle Park, and you’ll arrive at the east entrance of Karahori Shopping Arcade. It’s one of the city’s three great traditional shopping arcades along with Senbayashi and Komagawa––stay tuned for the profiles of Asahi and Higashi-Sumiyoshi wards. Karahori means “dry moat,” and the arcade runs along what used to be a water-free moat that was Osaka Castle’s outermost line of defense.

While Karahori Shotengai has been gradually shifting from mom-and-pop shops toward trendy eateries and such, that’s better than becoming a shutter-dori (ghostly shopping arcade where most stores are defunct), and it still has quite a few old-timey establishments and a pleasant grandma’s-house smell. The surrounding area miraculously escaped the flames during eight air raids that engulfed central Osaka during World War II, and is home to old machiya row houses, narrow back alleys, stairs connecting streets (due to the hilly terrain), and a few of the once-common mini-neighborhoods with a shared entrance where residents’ name plates hang. Legend has it that Enoki Daimyojin, a deity enshrined in an altar below a 650-year-old tree just north of Nagahori-dori, stopped the ring of fire from reaching the Karahori area to the south.

Quite possibly it was the wide street, still a canal at the time, that quenched the flames. Anyway, the shrine and the tree are a venerated local landmark, as are a number of nearby sacred trees in the middle of streets. They escaped chopping thanks to the deities inhabiting them, which it was believed would bring calamities upon the choppers, and they enshrine a snake deity, usually depicted as white and with a head at either end. Whatever it was that saved Karahori – the neighborhood bounded by Nagahori-dori to the north, Uemachi-suji to the west, Matsuyamachi-suji to the east, and Tanimachi 7-chome to the south – the area retains precious old-timey atmosphere sadly missing from most of central Osaka.

There’s a simmering conflict between preservationists, endeavoring to save, renovate and convert the picturesque, dilapidated wooden buildings and local scenery that evaded wartime destruction, and the rampaging real estate market. It’s an ironic dynamic when the neighborhood’s desirability leads to tearing down the old things that made it desirable in the first place and replacing them with bland apartment blocks. Still, off the main streets there are still many alleys and warrens so dense they seem immune to interference. Knock on wood.

Land of Dolls and Toys

At its western end, Karahori Shotengai terminates on Matsuyamachi-suji. The stretch of the avenue pronounced locally as “Maccha-machi,” to the north and south of the Matsuyamachi subway station, is the destination for all your doll and toy needs. Even as a shadow of its once-thriving self, the avenue has a fascinating mix of purveyors of high-end traditional dolls (like hina dolls for Girls’ Day on March 3 and gogatsu samurai dolls for Children’s Day, traditionally Boys’ Day, on May 5) and old-fashioned crafts, and dingy shops crammed to the gills with cheap plastic toys and novelties. Many stores’ wares change with the season, and you can get your summer fireworks, Halloween bric-a-brac, and Christmas decorations along with your anime character masks and industrial-size quantities of bouncy balls and rubber duckies.

Mean Streets

To the west of Matsuyamachi-suji, cross a bridge over the Higashi-Yokobori canal under the elevated highway and you are outside the former environs of Osaka Castle for the first time in this article. South of Nagahori-dori you are in Shimanouchi, a contender for sketchiest neighborhood in Osaka, and a certain victor if the contest is limited to Chuo Ward. Like Osaka itself, its name (literally “inside the island”) seems mysterious today, but as mentioned earlier most of the city was water until relatively recently, and this area with Dotonbori to the south, Nagahori-dori to the north, Higashi-Yokobori to the east, and Sakai-suji Ave. to the west was once entirely surrounded by rivers.

A swampy, low-lying quality lingers in Shimanouchi, famously home to many yakuza offices, as well as being the living place of choice for many foreign folks possibly drawn by cheap rents and anything-goes landlords, as well as hosts and hostesses working in neighboring Higashi-Shinsaibashi. The latter is Minami’s hottest nightlife spot, throbbing on a weekend evening, home during the morning hours to tumbleweeds and the occasional wobbly crew of pasty hosts straggling home from a night’s work.

Vicki! I – I Thought I Heard Your Voice!

Despite the derision toward Amerika-mura expressed above, there’s one wonderful local landmark at its northwest corner. Osaka Vicki, a building-sized mural by the American Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, towers above the elevated expressway on the south side of Nagahori-dori a few blocks west of Shinsaibashi. It was commissioned from Lichtenstein to give some color and excitement to a cooling tower for the Crysta Nagahori underground arcade.

Sacred Ground

Now we’ve reached the western edge of Chuo-ku, so let’s double back east to the area between Tanimachi 6-chome and Tanimachi 9-chome. All of this and the land to the south stretching down to Tennoji was formerly covered with temples, and quite a few remain, though most are engaged in regular Buddhist business and few are open to visitors. In this same area is Kozu-gu, a Shinto shrine so venerable that it appears in the opening line of the Osaka City anthem: Takatsu no miya no mukashi yori… (“Since the ancient days of Kozu Shrine…” Takatsu no miya is an alternate reading of the kanji for Kozu-gu).

The shrine has some interesting corners, and the northeast corner is known as the kimon (“demon gate”). This direction is believed to be frequented by all manner of bad astral juju, and this northeast-corner feature is intended to block evil forces from entering. Descend the stairs into the Kozu Shrine kimon and you may sense an ominous shift in the atmosphere, if you’re sensitive to these things. Don’t miss the in’yo-seki (yin-yang stones), a pair of large natural rocks reminiscent of male and female genitalia. On the opposite, northwest side of the shrine, descend another staircase if you’re struggling to end a bad relationship.

Leaving the grounds in this direction, there are stairs leading in two directions, one south toward Sennichimae-dori and the other in the quieter northward direction. The northern stairs are called the engiri kaidan (stairs for severing ties), and going down them with this intent is said to be effective for washing someone right out of your hair. The other stairs are the enmusubi kaidan, with the opposite function, but they don’t seem to have as much mystique.

Inhabited for many centuries of constant change, Chuo Ward is full of ghostly vestiges of the past peeking out from cracks in the concrete and steel. To taste the atmosphere of the Showa era (1926-1989), visit the Semba Center Building, actually a long series of buildings under the Hanshin Expressway, in the middle of Chuo O-dori. The outside was recently spruced up, but much of the interior including the underground dining and drinking section is a blast from the past.

The word “retro” in Japanese, a bit different from its English implication, describes such places where the clock seems to have been turned back. To the north of Chuo O-dori, in the Semba and Kitahama business districts,å are many examples of “retro architecture,” essentially prewar, Western-influenced brick and stone buildings. Enough are clustered around here that it’s easy to hit a bunch on one walking tour.

Some favorites are the Ikoma Building, topped with a 1930 modernist clock tower, on the west side of Sakai-suji a few blocks south of Kitahama Station (where the lions guarding Naniwa-bashi Bridge are also retro icons); the Aoyama-Fushimi Building (1921), covered with ivy descended from vines that used to grow on the walls of Koshien Stadium, also near Kitahama (from Sakai-suji, go west at the Fushimi-cho intersection); and the Shibakawa Building, further west in Fushimi-cho near Yodoyabashi, which looks like it belongs in Gotham City, with a touch of Asian influence. Inspired by the lessons of the Tokyo earthquake of 1923 to be built like a fortress, it contains a whisky bar on the first floor that’s fine for warming your cockles on a rainy night.

To paraphrase the Ramones, Chuo Ward really has it all. It’s not only central and convenient, but also has green open spaces, rich history, entertainment, and plenty of odd nooks and crannies. But one thing it sadly lacks is public baths (sento, the local “one-coin” bathhouses, as opposed to larger, newer, and more luxurious super sento facilities). Over the past 10 to 15 years, their number in the ward has dwindled from at least a dozen to approximately one, as elderly proprietors retire without successors, or sell out to take advantage of those sweet, sweet Chuo Ward property values.

This is not only a tragedy if you’re a hot water enthusiast: the number of sento in an area is directly correlated to its degree of the shitamachi atmosphere we all love. The ambience of old-school working-class districts is a hard-to-describe mixture of gritty, picturesque, and nostalgia-inducing (even if you weren’t around during the era it makes people nostalgic for). On that note, the next article in this series on Osaka’s wards will venture away from the center and into that realm known as “deep Osaka.” Watch this space!

Excellent arti, Colin! The Uemachi Plateau is mentioned in some of my fishing series as well, lots of history there. I enjoyed it in this article as well! Cheers, Wes