Dotonbori is Osaka as its most iconic. The area in the Namba district in the southern reaches of Chuo Ward, stretching along the Dotonbori Canal, is what most people in Japan and abroad think of first when picturing Osaka as a whole.

Dotonbori, that is Ebisu Bridge with all the dazzling neon signs all around it, including the landmark Glico Man advertising a major sweets manufacturer, with the Kani Doraku crab, a moving billboard in the shape of a giant crab advertising a crab restaurant, the giant fugu blowfish lantern in front of the Zubora-ya restaurant.

Dotonbori is the epitome of Osaka nightlife, crammed with restaurants and bars and clubs of all kinds.

Dotonbori, that’s where all the revelries take place when the Hanshin Tigers, Osaka’s iconic baseball team wins a game. Fans used to jump into the Dotonbori Canal from Ebisu Bridge to celebrate their team until the city erected glass walls alongside the bridge.

Hanshin Tigers fans threw a store front statue of Kentucky Fried Chicken’s Colonel Sanders into the canal in 1985, leading to the “Curse of Colonel Sanders”. The team didn’t win a major title for the following 18 years but rebounded before the statue was finally retrieved in 2009.

Dotonbori, that’s a place of magic, of glittering lights, large crowds and food in abundance.

The culture of kuidaore is said to have its roots in Dotonbori. Kuidaore translates loosely to “bankrupt yourself by eating”. The night before a debt collector would knock on the door, Osakans would take all their money and spend it on the most expensive and most delicious food. When the collector arrived, he would be met by a pauper without a yen in his pockets. That’s the Dotonbori spirit in a nutshell.

Even the iconic Glico Man has his dark undertones. In 1984, the chairman of the company was kidnapped right out of his home. A few days later, he managed to escape from his captors but the criminals turned to blackmailing his company, threatening to poison some of the products in the stores. The case made the national news for months and soon involved other sweets manufacturers as well. The culprits were never found.

Dotonbori, that’s Osaka with all its glamor, with all its contradictions.

Table of Contents

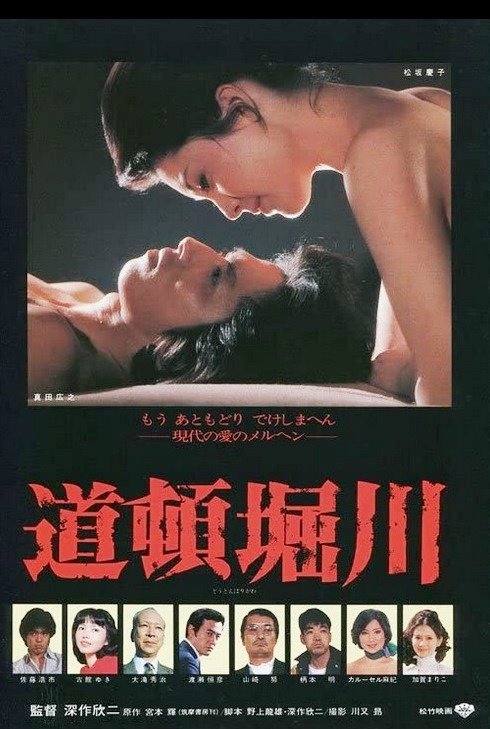

Dotonbori River (Japan, 1982) 道頓堀川

Kinji Fukasaku’s 1982 movie Dotonbori River, also known as Lovers Lost in English-language territories, and as Dotonborigawa in Japanese, plays on all those contradictions. The movie is based on the novel Dotonbori River by Tera Miyamoto who also penned the novel Muddy River, turned into a movie by the same title by Kohei Oguri in 1981, find a review here.

The film, a Shochiku Studio production, opens with shots of the nightly neon lights of Dotonbori, including the Glico Man. Cut to dawn and a young painter / art college student named Kunihiko Yasuoka (Hiroyuki Sanada) trying to capture the scenery of the Dotonbori Canal on canvas. A young woman walking her dog approaches. The dog running freely without a leash brings Kunihiko’s carefully propped up and almost finished painting tumbling to the ground. Thus boy meets girl, in this case, Kunihiko meets the very apologetic Machiko (Keiko Matsusaka). They like each other immediately although Machiko is clearly about 10 years older than Kunihiko.

Kunihiko works and lives at a kissaten (Japanese coffee house). The master of the coffee house, Tetsuo Takeuchi (Tsutomo Yamazaki) has taken him in when Kunihiko’s mother died, his only close relative. Takeuchi’s son Masao (Koichi Sato) is Kunihiko’s best friend from school.

The film tells two stories, both very contradictory in themselves and often intersecting.

By coincidence, through Mr. Takeuchi, his coffee house boss, Kunihiko meets Machiko again at the small izakaya bar she operates. Turns out later that she is a former prostitute and that the bar has been bestowed on her by her sugar-daddy, an elderly rich man. Still, love between the Kunihiko and Machiko soon starts to blossom.

Mr. Takeuchi’s coffee house attracts a wild crowd, foremost a group of rowdy transvestites headed by a certain Kaoru (Maki Carrousel, a real-life transvestite actor).

Takeuchi’s son Masao on the other hand is a young master of nine-ball billiards, a game known to Americans as pool.

Pool is usually a colloquial game just played for fun among friends and if there are any bets involved, they rarely exceed a pitcher of beer.

Not so in Dotonbori in the early 1980s. The movie depicts a secretive world of pool hustlers betting on serious money. The first game we see in the movie, Masao against a drug addicted old pool shark, has Masao win 300.000 Yen.

So, that’s the two stories the film tells… the unlikely love story between art student / coffee house employee Kunihiko and the much more experienced Machiko and a tragic story of gambling going to the extremes.

Turns out eventually that Mr. Takeuchi, Masao’s father and Kunihiko’s coffee house boss, had been a pool shark of epic dimensions two decades earlier. He was so mad about the game that he made his wife (Masao’s mother) a hooker to earn him the Yen he needed to play. With fatal consequences for her.

While the movie moves along at a rather slow speed for most of the time, in the last half hour, all those stories come together. Masao plays the game of his life against his father in a pool hall run by a certain Yuki (Mariko Kaga, great as always), Machiko lovingly prepares food for Kunihiko after finally shaking off her sugar-daddy… but Kaoru, the transvestite, accidentally enters the picture with fatal consequences.

Dotonbori River, the film, packs it all in. The glamor of Dotonbori, the sometimes very straightforward and trusty relationships people engage in but also all the weirdness, violence and addictions rife in the area. Addiction to drugs, addiction to gambling, addiction to erotic attention.

The latter comes to the fore when an otherwise very minor female character arrives at the coffee house late at night and performs a frenetic nude dance in front of Kunihiko.

That dance is one of the movie’s most famous scenes even though it has no bearing on any of the stories told in the film. But it looks absolutely beautiful and greatly contrasts with the fiery fights at the pool tables.

The Director: Kinji Fukasaku

Kinji Fukasaku (1930 – 2003), whose career spanned the years 1961 to 2003, can’t be grouped into any of the various Japanese cinematic movements of his time such as, say, the Japanese New Wave. Fukasaku worked in many different genres and styles, starting out with yakuza movies in the 1960s. His gritty, violent and highly energetic Battles Without Honor and Humanity series (1973 – 1976) depicting gangster turf wars in post-WWII Hiroshima was his break-through as major director. He continued his career with samurai dramas, war films and directed in 1980 Japan’s up to then most expensive production, Virus about a man-made epidemic that wipes out all of humanity safe for a few souls in Antarctica, starring Sonny Chiba, George Kennedy, Robert Vaughn and Olivia Hussey.

Fukasaku achieved late international acclaim for his hyper-violent Battle Royal (2000), starring Takeshi Kitano and telling the dystopian story of school children dropped on a remote island and forced to kill each other until only one survivor is left.

As different as all those films were, they all featured a high level of energy, often expressed through cinéma vérité-inspired shaky camera moves.

Compared to his major works, Dotonbori River seems like a very quiet, leisurely project for Fukasaku. Yet his trademark high energy is infusing the movie thoroughly, bringing out the grit and darkness behind the dizzying lights of Dotonbori. The film contains very little violence (though there is some), focusing instead on the tensions mounting between the characters.

The film won Fukasaku the Japan Film Academy Prize as Best Director of the Year.

Osaka Locations

All exteriors were shot right on location in Osaka, for the most part right there in Dotonbori. All interiors however, including the various pool halls, were shot at a Shochiku studio set.

While the front credits roll, we are treated to shaky night shots of the immediate environs of Ebisu Bridge. Lots of neon lights and the Glico Man clearly in sight.

Cut to Kunihiko, the young painter standing on a bridge over the Dotonbori Canal with his canvas. That bridge is the Daikoku Bridge, a small bridge about 200m west of Dotonbori Bridge. Kunihiko is facing East, painting Dotonbori Bridge and with it, central Dotonbori.

On this Daikoku Bridge, Kunihiko has his first encounter with Machiko, his later love interest.

Cut to the coffee house where Kunihiko lives and works. The coffee house is called “River”, written in Japanese katakana letters: リバー (ribah). It’s clearly on Dotonbori Canal but where?

The somewhat mysterious Japanese-language Osaka blog Idle Musings of a Mountain Stream Poet (渓流詩人の徒然日記) offers a location map for the movie and a few hints.

The River café, the Mountain Stream Poet claims, used to be a traditional Japanese coffee house named Ogura, located on the north side of Dotonbori Canal, in the second building to the East from Ebisu Bridge, now housing a convenience store. Indeed, at that location you find today the Family Mart Souemon-cho.

Further locations identified by the Mountain Stream Poet include the Ume no Ki (Plum Tree) bar operated by Machiko as well the drag show club where Kaoru performs on stage. Both are a few steps south of Aiau Bridge towards the Eastern end of Dotonbori.

The pool hall where Masao has his final tense game with his father is called the Kohaku (Red & White) Pool Hall in the movie. According to the Mountain Stream Poet that pool hall was just a few steps further south from Aiau Bridge. Following his directions, a pool hall can be found at that exact location even today. It’s called Tamatsuya, using a generic but very old fashioned term for pool hall as its name. In the movie, the pool hall is in the basement, today’s real pool hall at that location can be found on the 2nd floor of the building.

Kunihiko’s accidental but fatal encounter with Kaoru at the end of the movie, the bloodiest scene of movie, also takes place in the immediate vicinity of Aiau Bridge.

In one of their happiest moments, Kunihiko and Machiko meet in front of the Shinsaibashi Shopping Arcade, close to Dotonbori. The name of the shopping mall clearly shows up on screen.

After saying sayonara to Machiko and heading back towards Dotonbori, Kunihiko crosses the old Shinsaibashi Bridge. A locally much beloved pedestrian bridge at the time of filming, the old Shinsaibashi Bridge was dismantled in 1995. That same bridge also made a cameo in the 1989 Osaka crime action movie Black Rain.

Osaka Castle isn’t that close to Dotonbori but it’s in walking distance or just a short subway ride away. Fukasaku made sure to get a shot of the castle in his movie. Kunihiko and Machiko have a date in a park at a riverside with the castle clearly showing up in the background.

Dotonbori River is a movie not only taking place in Osaka but really making great use of the featured Osaka locations. The story being set in contemporary times certainly helped: Fukasaku and his team could just go out and record the part of the city the movie was set in as it looked at the time. Glorious, gritty and real. The film is a true time capsule.