Osaka has hosted many major international events over the years, such as the G20 Summit in 2019, and soon to include the 2025 World Expo. With a foreign population exceeded only by Tokyo, it is also one of Japan’s most international cities. It is therefore perhaps no surprise that Osaka has a long diplomatic history, going back to the early days of the Japanese nation. This essay will take a mostly chronological approach, beginning by looking at early port towns in the Osaka area and their important diplomatic role in ancient Japan. Following this, the focus will move to the long space between the classical and modern eras, during which time foreign relations were limited first by extended political instability and then by a period of near-total isolation from the outside world. This will then lead on to the modern era, where Japan played a greater role on the global stage, looking at Osaka’s position within Japan’s foreign relations, as well as projects and events specific to Osaka, such as summits and sister city relationships. Finally, there will be a more in-depth look into one of Osaka’s most famous international events, the 1970 World Expo, and plans for the next exposition in 2025. Diplomatic history of Osaka

Table of Contents

Diplomacy in ancient Osaka

The centre of diplomacy in Japan today is the capital city, Tokyo. It is the most cosmopolitan city in Japan, with a far greater number of foreign residents than any other municipality.[1] Other Japanese cities renowned for foreign exchange include Nagasaki, which received some of the first Portuguese traders and missionaries in the 16th century CE, and was then for around two hundred years Japan’s only official international port.[2] However, though Nagasaki was of great importance during the sakoku era, when foreign trade and diplomacy was extremely limited, before that point it had existed for only a short time, as a small fishing village.[3] Tokyo’s time as the official capital of Japan began even later, in the 19th century. Previously, under the name of Edo, it was the de facto centre of political power for over two centuries of samurai rule, but like Nagasaki, it was a fairly new town, built around the 15th-century Edo Castle.[4] However, the history of a centralised Japanese state goes back roughly another thousand years, to a time when the area of modern Tokyo was on the outskirts of the developing nation.[5] The driving force behind the consolidation of political authority was the Yamato clan, whose power base was around the area that is now Nara Prefecture; therefore, the centre of early Japanese politics was in the surrounding region, roughly corresponding to Kansai today.

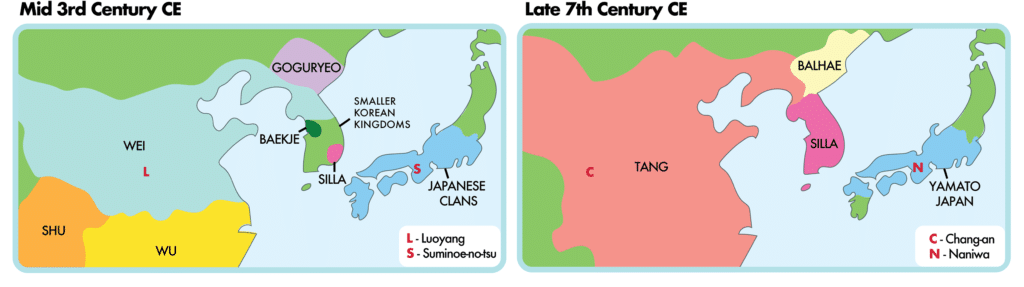

Even before the imperial government first took shape, Japanese clans were involved in diplomacy and trade with nations in mainland Asia, specifically those that would later become today’s China and Korea. In the 3rd century CE, the Chinese kingdom of Wei produced the earliest extant descriptions of Japan, with passages in an official dynastic history mentioning envoys sent to the earlier Han dynasty by various smaller states within Wa – China’s first name for Japan.[6] Around this time, several states existed on the Korean peninsula too, with the largest being the kingdoms of Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla.[7] These Korean kingdoms were central to early Japan’s international relations, as China suffered from political volatility for several centuries and therefore the relatively stable regimes in Korea were a more reliable source of culture.[8] Interactions with Baekje and Silla brought Chinese philosophy and language to Japan, including Confucian and Buddhist texts. One of the earliest historical texts written in Japan, the 8th-century Nihon shoki, suggests that Baekje was a particularly valuable ally, regularly exchanging goods, knowledge and military aid.[9] In the late 6th century, China was reunited under one government by the Sui Dynasty, which was replaced soon afterwards by the more enduring Tang Dynasty.[10] The Yamato regime in Japan was quick to send envoys to Sui and Tang China and establish a relationship with this powerful neighbour. The Korean peninsula, too, was soon unified by the kingdom of Silla with military assistance from Tang Chinese forces, making a good relationship with China even more important for Japan. The Sinocentric order that developed during this time laid the basic rules for diplomacy in ancient East Asia.

Among Japan’s earliest international ports was Suminoe-no-tsu, which began as a fishing village near the site of Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine, an important Shinto shrine built in the 3rd century CE in what is now southern Osaka City.[11] As well as being the main departure point for envoys and military vessels in the time before the Yamato clan secured control, Suminoe-no-tsu is said to have been Japan’s access point to the Silk Road.[12] However, although Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine continued to have social and cultural value, the role of Suminoe-no-tsu as an international port was soon replaced by another settlement a little to the north. It is unclear when exactly the new port, named Naniwa-zu, was founded, but it is likely that its importance grew as the Yamato rulers reacted to events going on in the Korean peninsula, when Japan’s traditional ally of Baekje began to come under attack from Silla.[13] At the time, the geography of the region was significantly different from today, which meant that though the locations of Suminoe-no-tsu and Naniwa-zu are now several kilometres inland, they were then coastal settlements, and to their immediate east was a large lake taking up much of what is now eastern Osaka Prefecture.[14] Especially with the addition of canals, this gave Naniwa-zu a great strategic position.

Evidence of the Osaka area’s value to early Japan’s foreign relations comes in various forms. Facilities were constructed for purposes such as holding diplomatic functions and housing visiting envoys.[15] Today, there is a bridge in Osaka called Koraibashi, which is said to be named after a hall used for entertaining Korean envoys.[16] The area was also central to one of the key cultural imports of the era, with Shitennoji in today’s Tennoji Ward being established in the late 6th century as Japan’s first officially commissioned Buddhist temple.[17] Under the order of the regent Prince Shotoku, construction was even carried out by some of the area’s existing foreign residents: Korean carpenters from Baekje who went on to found Kongo Gumi, perhaps the world’s oldest continually operating company.[18] The height of Naniwa-zu’s importance to the early Japanese state came in the mid-7th century when, as part of wide-ranging administrative reforms, Emperor Kotoku moved the national capital from Asuka in the Nara area to Naniwa.[19] According to tradition, Naniwa was the capital on one previous occasion as well, during the time of the semi-legendary Emperor Nintoku, whose alleged burial place can be seen today in southern Osaka Prefecture.[20] However, unlike Nintoku, Kotoku’s reign is supported by clear archaeological evidence, including the remains of Naniwa’s palace site which began to be excavated in the 1950s.[21] Naniwa’s time as the capital was short-lived, as the capital was moved back to the Yamato region after Kotoku’s death around ten years later, but it continued to have diplomatic value. Kotoku’s successor used Naniwa as a base for providing military support to Baekje during what would prove to be the decisive war with Silla, and other emperors made use of the palace during the remainder of the 7th century, receiving diplomats from Tang China and Silla. Even for many years after the capital was moved further away still – this time to Heian-kyo, now known as Kyoto – the port of Naniwa-zu continued to be a common point of departure for envoys. These missions included that of Kukai, a monk best known for bringing influential Buddhist teachings from China to Japan and founding Shingon Buddhism, one of the religion’s main sects in Japan.[22] However, the relocation of the capital to Heian-kyo followed closely after the creation of a new canal enabling boats to move from the Seto Inland Sea to the capital without passing through Naniwa whatsoever. As a result of these developments, although Naniwa-zu was used for diplomatic missions at least as late as the early 9th century, its influence dwindled during this time.

After Naniwa lost its central role in the politics of the era, another port emerged in the same area, called Watanabe-no-tsu.[23] This town was valued locally as a trading port and as the starting point for pilgrimages to Shitennoji, Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine and other major shrines to the south.[24] However, this was as far as its importance went, and Watanabe-no-tsu did not inherit Naniwa’s crucial role in international diplomacy. Therefore, while the ports of Suminoe-no-tsu and Naniwa-zu – particularly the latter’s brief stint as the capital – had been important for sending and receiving missions and housing diplomats, this represented the end of the Osaka region’s part in the diplomacy of early Japan. The Heian Period, during which classical culture flourished in the imperial court in Heian-kyo, continued for over three hundred years, but this too came to an end, with political instability eventually taking over and leading into the mediaeval era of Japanese history: the time when the city of Osaka finally came into being.

The mediaeval and early modern eras

The Heian Period ended chaotically, with the Genpei War breaking out between rival clans and resulting, eventually, in the establishment of a military government in Kamakura, near modern-day Yokohama.[25] Though there was still an imperial court in Kyoto, in practice the emperor had little to no political power and military rule was in place in one form or another for close to seven hundred years. The reign of the samurai or warrior class was not entirely without interruption, however: governments were usurped or overthrown at several points in the following centuries, and it was only after an extended period of civil war around the 16th century that peace and stability could be established. The earlier period of military rule is notable for attempted Mongol invasions of Japan and for the first appearance of Western traders and missionaries, while the largely peaceful Edo Period of early modern Japan is famed for the policy of national seclusion known as sakoku.[26] This section will look at some of the ways in which the Osaka area, especially the growing cities of Osaka and Sakai, was involved in Japan’s foreign relations during this long historical period.

Source: National Diet Library https://rnavi.ndl.go.jp/research_guide/entry/post-1164.php

Under the first military government following the Genpei War, Japan’s foreign relations were limited. Since the Heian Period, there had not officially been diplomatic ties with Korea and China, but in terms of trade and cultural exchange, relationships with these neighbours were still important, with Japan’s southern island of Kyushu being the primary point of contact.[27] At this time, the spread of the Mongol Empire in mainland Asia played an increasingly significant role in regional politics. This situation, together with Japan’s ongoing trade with the mainland, the problem of Japanese pirates operating around China and Korea, and the presence of foreign nationals in Japan, forced the military leaders to develop diplomatic policies. As the Mongols increased their influence in China and Korea, they sought to pull Japan into their new international order, but after a short period of diplomatic exchange, the Mongol Empire attempted multiple invasions. Though these attacks proved unsuccessful, in part due to typhoons disrupting the invasions, the resulting financial problems contributed to the fall of the Kamakura regime.[28]

It was during the following Muromachi Period, when a new military government ruled from near Kyoto, that the city of Sakai began to develop into a major port. Near Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine, Sakai had existed for a long time as a stop on pilgrimage routes, but its value as a trading port grew vastly after the national regime change, and after the Muromachi Period too came to an end and gave way to political disunity, it became one of the main centres for trade in Japan.[29] From the late 15th century, tribute missions were sent from Sakai to China – at this point ruled by the Ming Dynasty – effectively as private ambassadors working on behalf of powerful clans, temples and merchants. Traders from the Ryukyu kingdom in today’s Okinawa travelled to Sakai, bringing goods from Southeast Asia and elsewhere; merchants from Sakai also moved in the opposite direction, resulting in a rivalry with the port of Hakata in Kyushu. Besides trade with nearby cultures like China and Ryukyu, mediaeval Sakai is also notable for its connection to early Western explorers, particularly Jesuit missionaries. Francis Xavier, the first such missionary to visit Japan, was warmly received in Sakai by Hibiya Ryokei in the mid-16th century.[30] The Hibiya merchant family became well-known Christians and had connections around the country to give support to missionaries following Xavier.[31] Among others, these included Alessandro Valignano, who wrote of his impressed reaction to Sakai’s prosperity and status as an unusually independent city, as well as the culture of tea ceremony, which was revolutionised in Sakai during this period.[32] Evidently, Sakai was something of a hotspot for foreign culture, and not only for domestic trade. In the latter respect, however, its strong position would soon be eclipsed by Osaka, the city founded north of Sakai around this time.

Source: Sakai Tourism and Convention Bureau https://www.sakai-tcb.or.jp/about-sakai/sakaimatsuri/origin/

Osaka was based around Osaka Castle, which was the stronghold of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of the key figures in reunifying Japan after the era of civil war that followed the Muromachi Period. This meant that for the time he was in power in the late 16th century, the growing city was Japan’s political centre. Though Hideyoshi was renowned for his clever approach to domestic diplomacy, his rule also saw great foreign policy shifts, including brutal crackdowns on Christian missionaries and a goal of conquering Ming China.[33] He demanded that the Korean kingdom of Joseon allow Japanese forces to pass through to China, but after Joseon – an ally of China – refused, he launched an invasion of the Korean peninsula. After a protracted war effort that eventually showed little prospect of a successful result, Osaka Castle became the site of attempted peace negotiations with representatives of Joseon and Ming China.[34] These talks fell apart and Hideyoshi gained nothing from the war; with the war still unfinished, he died, and soon afterwards the regime he had created collapsed too, leaving Tokugawa Ieyasu to complete the project of reunifying Japan. It was Tokugawa who moved the base of political power to Edo, the forerunner of modern-day Tokyo and namesake of the Edo Period.[35] The largely peaceful Edo Period continued for over two hundred years and was marked by the implementation of the sakoku policy, which severely restricted foreign exchange. Therefore, Osaka’s significant position under Hideyoshi was short-lived, and though the city became a major economic centre, overtaking Sakai, international trade and diplomacy were no longer among its main roles.

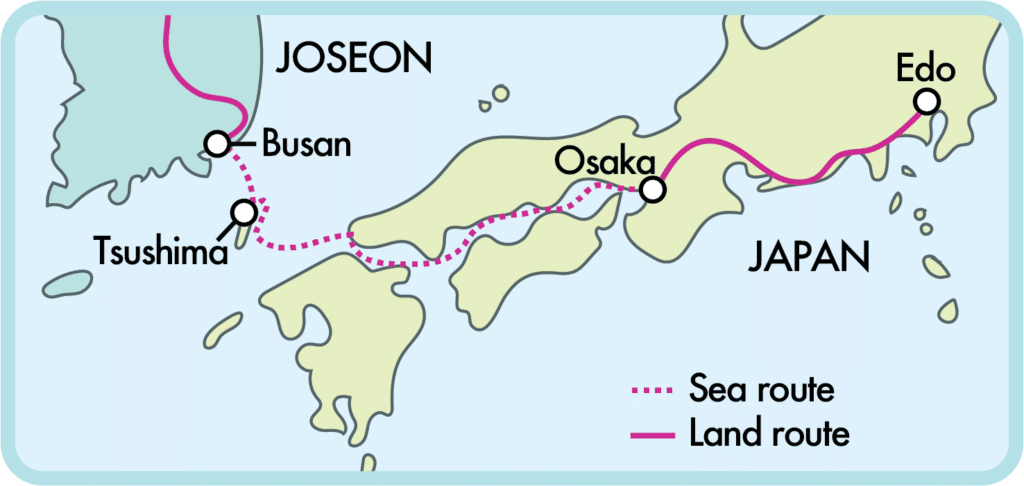

The era of sakoku is famous for Japan’s self-imposed isolation from the outside world, with trade monopolised by the government and Japanese people banned from travelling out of or into the country, while Nagasaki alone was open to Dutch traders. However, it is worth pointing out that historians have disputed the extent of these policies. Not only was trade permitted with neighbouring countries like Ryukyu, but some of these trading relationships were private endeavours with approval from the government.[36] Indeed, it has been argued that in the context of the East Asian cultural sphere, the earlier Japanese invasions of Korea had had a greater negative impact than any policies during sakoku. From the early 17th century, just before the Edo Period began, exchange of envoys between Joseon and Japan resumed, and this continued throughout the period.[37] The typical route for the missions from Joseon began at the Korean port of Busan, from where a party of at least three hundred would sail to Tsushima, an island north of Kyushu, and then to Osaka, accompanied by escorts from Tsushima.[38] At Osaka, some of their number would stop there, while the others continued over land to Edo. In this way, Osaka’s value as a domestic trading port gave it a role, however minor, in foreign diplomacy, particularly with Korea.

Besides official foreign missions, Osaka is also connected to Edo Period diplomacy in more surprising ways. For example, in 1965 an Osaka merchant’s clerk named Dembei happened to be the only survivor after a commercial trip to Edo was blown off course by a typhoon and shipwrecked in eastern Siberia.[39] After being found – and briefly believed to have come from an Indian country called “Uzaka” rather than “Osaka” – Dembei was brought before Tsar Peter the Great and questioned about Japan.[40] Though he was not knowledgeable about Japanese politics, he mentioned that trade with the Dutch was permitted in Nagasaki, piquing the Tsar’s interest in Japan. A Japanese language school was soon founded; despite a promise that Dembei would be returned to Osaka in exchange for teaching Japanese, this never came to pass, possibly due to no Japanese education taking place after all.[41] Nevertheless, this represents an interesting episode in how international exchange occurred during the Edo Period in spite of the sakoku policy.

Osaka and nearby cities once again played a more prominent role in diplomacy at the end of the Edo Period, when the shogun was under pressure from Western powers to reopen and modernise the country. During the domestic turmoil of these years, Osaka Castle’s strategic value became important again, and the last two leaders of the military government used it for conducting diplomacy.[42] Foreign dignitaries otherwise stationed in Edo, such as those from Britain, were hosted at the castle for meetings right before the fall of the regime.[43] During those talks, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the final shogun, is said to have expressed a desire to reform government, but in spite of the positive impression of ambassadors who met him then, he lost his position soon afterwards and Japan’s modern era began. After Osaka was taken by rebel forces, it was then used by the new government for diplomacy too: Emperor Meiji spoke to foreign representatives in Osaka to seek international recognition of the new regime as Japan’s legitimate government. At the same time, there was also resistance to the then-recent reopening of Japan to international trade. In February of 1968, immediately after the new government took power, the Kobe Incident took place.[44] Around Sannomiya Shrine, in what is now downtown Kobe, a fairly minor dispute over local customs resulted in an exchange of fire between Japanese and foreign troops and soon the port was temporarily occupied by foreign forces. This caused great concern over the possible consequences, and the incident was quickly ended when the Japanese perpetrator of the initial assault was ordered to publicly perform ritual suicide. Only weeks later another diplomatic crisis surrounded Osaka, when eleven French sailors were killed in Sakai, causing French authorities to demand compensation and the execution of those responsible.[45] The Osaka Court determined that twenty of the perpetrators would be killed, and the incident is remembered for the dramatic nature of the execution, in which eleven men disembowelled themselves before a French representative requested that the last nine be pardoned.

Together with the diplomatic meetings at Osaka Castle, the Kobe and Sakai Incidents demonstrate some of the major changes brought about during the mediaeval and early modern eras. Whereas ancient Osaka was the site of vibrant international exchange with East Asian neighbours in Naniwa, and Sakai welcomed missionaries from distant lands hundreds of years later, events in and around Osaka on the cusp of modernity showed tension between Japan’s ageing feudalistic system and a new global order. As we will see in the next section, Japan’s place in this new order opened up new diplomatic opportunities for Osaka.

Modern diplomatic history of Osaka

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 abolished Japan’s existing military government and returned political authority to the emperor, setting the country on a course of reform and modernisation. In the same year, a small port called Kawaguchi in what was then Osaka’s western outskirts – now part of Nishi Ward – was opened as one of several foreign settlements available for foreigners to live and do business.[46] This came about as the result of earlier treaties stipulating that Osaka’s foreign settlement should open in 1863, but together with the opening of Kobe, this was delayed repeatedly.[47] The postponement in the case of these two in particular was ostensibly due to concerns that allowing foreign traders so close to the emperor’s home of Kyoto would be dangerous, as many in the area were opposed to outsiders; however, it is also possible that the goal was to protect Osaka itself, which had become a vital economic hub.[48] Kawaguchi, which had history as an international port, having been the arrival point for envoys from Joseon and Ryukyu in the Edo Period, was smaller in size than any of the other foreign settlements.[49] Even so, this did not prevent it from housing nationals of several different countries, including Britain, Germany, the United States and others.[50] Merchants in Kawaguchi brought food, technologies and practices that were still unusual to Japanese people, such as bread, gas power and Western architectural styles. Among the most renowned figures associated with the Kawaguchi foreign settlement are four Dutch engineers.[51] From the early 1870s, Johannis de Rijke, together with three others whom he advised the Japanese government to invite, worked on improving the Yodo River and Osaka harbour, among many other major civil engineering works around the country. During their time in Osaka, they each lived in or near the Kawaguchi foreign settlement.

Source: Momoyama Gakuin University https://www.andrew.ac.jp/nenshi/concession_p1.htm

However, though the likes of de Rijke and his colleagues show the benefits of the foreign settlement, it was not generally considered to be a success for Osaka. The settlement was small, the port’s area was unsuitable for large merchant ships and locals were largely uninterested in trading with the foreigners.[52] This led the majority to give up on Osaka and relocate to the nearby Kobe settlement instead. The foreign settlement in Kobe turned out to be extremely successful, transforming a village around Ikuta Shrine into a nationally famous centre of cosmopolitan culture.[53] In 2018, Kobe City celebrated the 150th anniversary of the port’s opening; in contrast, the same anniversary in Osaka was not widely promoted. Still, although the Kawaguchi foreign settlement’s traders largely abandoned it for the most successful Kobe settlement, this was not the end of the story for Kawaguchi. After the merchants left, many Christian missionaries moved in and established schools and hospitals. These include the predecessor of Momoyama Gakuin University – also called St Andrew’s University – which later moved to the Tennoji area and then to southern Osaka Prefecture.[54] The activities of these missionaries can be seen also in what remains of the settlement: though most of the buildings that once stood there are now gone, the Kawaguchi Christ Church Cathedral is still there today.[55] While the foreign settlement is not particularly well-remembered now, it remains an interesting chapter in the history of Osaka’s contact with the world beyond Japan.

The foreign settlement system continued for only a few decades, with the later revision of treaties resulting in the official abolition of the settlements in 1899. In some cases, the legacy of the settlement lasted much longer, such as in Nagasaki, where some of the first foreign consulates in Japan were founded in the mid-19th century and continued to serve that role for many years after the foreign settlements ceased to operate.[56] Osaka – and the failed settlement at Kawaguchi – was unlike Nagasaki in this respect, but today it is home to more consulates than any other city in the country, responsible for the diplomatic missions of dozens of countries in western Japan.[57] This proliferation of consulates in Osaka is a postwar phenomenon, with many having moved to Osaka relatively recently. In a reversal of the trend of merchants moving from Osaka to Kobe in the late 19th century, a number of consulates have relocated from Kobe to Osaka.[58] For example, the German Consulate General has a long history, first being established in Kobe in the years following the port’s opening as a foreign settlement.[59] In those early days, many Germans lived in the area, with the number rising significantly after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 hit the Tokyo area and prompted people of all nationalities to move to Kansai in droves. The consulate moved several times, and was also closed and reopened more than once because of political shifts, not least during the First World War, when Japan and Germany were enemies, and after the Second World War, when they were allied. After around a century since the consulate’s founding, Kobe too was badly affected by an earthquake, the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake, leading to the relocation of the consulate to Osaka’s Umeda Sky Building in 1997. Among various cultural events organised by the consulate today is the German Christmas Market, which takes place annually outside the Sky Building.[60]

Other consulates in Osaka include the Consulate General of South Korea, which dates back as far as 1949, just after the independent republic of Korea was founded.[61] The Korean ambassador established an office for the diplomatic mission in Tokyo and in the same year, a branch office was opened in the Shinsaibashi area of Osaka. After Japan and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) normalised diplomatic relations in 1965, the Tokyo office was upgraded to an embassy, and the Osaka office to a consulate general. This long-standing consulate is just one of many representations of the close association between Osaka and Korea, a connection which has existed since the days of Naniwa-zu. After having been an important port for envoys travelling between Japan and Korea for hundreds of years, a commercial sailing route opened in 1923, going between Osaka and the Korean island of Jeju.[62] It is also important that Osaka was one of Japan’s main industrial centres at the time, as many of those coming in from the recently-annexed Korean peninsula were labourers, particularly in factories. This was the origin of the significant Korean minority population in Osaka, which remains one of Japan’s largest.

Due to this relatively high concentration, issues affecting ethnic Koreans throughout Japan are therefore especially significant in Osaka, such as nationality. When Korea gained independence after the Second World War, Korean residents in Japan lost Japanese nationality; when Japan later formed ties with South Korea, they had to choose between South Korean, Japanese or no nationality.[63] This has continued to be a problem for many, creating a difficult choice between maintaining the nationality of one’s family, and benefiting from being a citizen of the country where one lives. Soon after the conclusion of the Second World War, two rival organisations for Koreans in Japan emerged, the pro-North Chongryon and pro-South Mindan.[64] Chongryon has been influential since its founding, especially in the early years, and for decades organised the repatriation of many Koreans to North Korea.[65] A large number of those leaving Japan for supposed prosperity in North Korea were living in Osaka’s Tsuruhashi district – still one of the main areas for Koreans in Japan – including Ko Young-hee, who was born and raised in Osaka and later became the mother of current North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.[66] Besides repatriation campaigns and establishing schools, Chongryon also has an interesting position as the closest thing to a North Korean diplomatic mission in Japan. As Osaka is home to such a large Korean population, there are many Chongryon offices in the prefecture.[67] Controversy has arisen on many occasions in connection with Chongryon, such as disputes in recent years over the halting of prefectural and municipal subsidies to Chongryon-backed schools.[68] However, Chongryon is not as influential as it once was, and even in education, traditionally one of its main areas, various alternative approaches have emerged. Osaka City and Prefecture have been central to many developments in education for children of Korean ethnicity, with groups emerging particularly in the 1980s stressing opposition to ethnic discrimination rather than emphasising nationality.[69] These groups were generally aligned with Mintoren, a more recent alternative to Chongryon and Mindan, which has been linked to various movements for minority rights, such as the right to vote in local elections. The varied attitudes of groups and individuals towards issues like nationality and ethnicity can add an extra layer of complication; diplomatic disputes sometimes arise as a result, and especially as Osaka becomes an increasingly cosmopolitan city, these need to be handled carefully.

Another way in which Osaka has been involved in postwar international diplomacy is through exchange relationships with cities around the world. Beginning as early as 1957, Osaka City has formed eight sister or friendship city affiliations, as well as various other connections under names such as “business partner city” and “friendship port”.[70] Furthermore, the prefecture as a whole has formed partnerships with cities and regions in several countries, while other municipalities within Osaka Prefecture have their own international relationships.[71] The first of these was the sister city affiliation between Osaka and San Francisco.[72] This relationship was declared only a few years after the founding of the Sister Cities International initiative, and not much more than a decade after the end of the Second World War. A major focus was business; indeed, one of Osaka’s main representatives during early discussions was Sugi Michisuke, then the president of the Osaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry, who also had founded the Japan External Trade Organisation (JETRO) in 1951, in part to promote Kansai trade. The sister city relationship led to many exchange programmes and events, with the 60th anniversary being celebrated in 2017.[73] Sadly, in the same year a diplomatic dispute flared up after a statue memorialising victims of Japanese wartime atrocities in East Asia was displayed in San Francisco, eventually resulting in Osaka Mayor Yoshimura Hirofumi terminating the sister city agreement.[74] However, in spite of this, Osaka City’s official website continues to list San Francisco as a “friendship port” alongside Busan in South Korea and others, while the SF-Osaka Sister City Association in San Francisco has expressed a firm intention to persevere with their exchange activities.[75]

Source: SF-Osaka Sister City Association https://www.sf-osaka.org/

Osaka also has sister city relationships with cities including St Petersburg and Shanghai, enabling the promotion of business interests, tourism and other goals. In Shanghai, Osaka City and Prefecture also maintain an overseas office, which is focused especially on creating economic links between the two cities.[76] Besides the sister city agreement, Osaka and Shanghai share a strong history of cultural exchange in the 20th century, with Western music in particular connecting the two; some of Osaka’s most celebrated musicians in the city’s jazz boom of the 1920s spent time in Shanghai.[77] Other commonalities include having been host cities of World Expos, a feature shared with other sister cities Chicago, Melbourne and Hamburg.[78] Even though political issues can sometimes stand in the way, as in the San Francisco case, sister city and similar relationships are a key example of how Osaka and other cities can engage in diplomatic exchange at a local level.

Osaka’s influence on Japanese foreign relations is somewhat limited. Politicians from Osaka have not often been selected for important foreign policy positions such as Minister for Foreign Affairs, but there have been some ambassadors and others in diplomatic roles from Osaka over the years, such as Sugi Michisuke, the JETRO founder mentioned earlier. These also include Akasaka Kiyotaka, whose impressive CV includes holding major positions in the World Trade Organisation’s predecessor organisation, the World Health Organisation and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.[79] More recently he has worked as Under-Secretary-General for Communications and Public Information at the United Nations. Besides being the origin of diplomats such as Akasaka, Osaka has also been selected as the host for various summits and other international events. For example, in 1995 Osaka hosted the seventh annual meeting of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), an important regional economic forum with members on both side of the Pacific.[80] The Osaka Action Agenda came out of these talks, in which Japanese leaders’ idea of non-discriminatory “open regionalism” was laid out.[81] Osaka was also chosen as the site for Japan’s first G20 summit in 2019. Information about the host city emphasised Osaka’s history as an economic centre, hinting at its relevance to international trade talks.[82] Other important items on the agenda included data governance and climate issues, a growing concern as extreme weather events in Japan have increased in recent years.[83] The arrival of many major world leaders in Osaka resulted in a need for unprecedented levels of security: traffic restrictions were implemented while schools and businesses closed at the time of the event.[84] While the summit came under criticism for a lack of progress on some of the key issues, for at least a brief moment Osaka was at the centre of global diplomacy.

Source: The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/29/g20-summit-osaka-japan-trade-wars-liberalism

The modern era has exposed Osaka to the world on a level never previously seen. Though it was a vital port for hundreds of years, the scope of Osaka’s connections was generally restricted to Japan itself and its most immediate neighbours. The changes that occurred in Japan’s relationship with the outside world in the late 19th century therefore had a profound effect on Osaka, beginning with the opening of the Kawaguchi foreign settlement. Though Kawaguchi is not remembered as a great success story, it introduced foreign traders and missionaries to Osaka, and the more celebrated port in nearby Kobe gave rise to an international community in the area. Osaka’s development as an industrial and commercial hub made it a clear choice for consulates, as well as the destination for many workers from Korea, who became the city’s biggest ethnic minority group. This is a crucial part of Osaka’s increasing cosmopolitanism, which is arguably just as important to the city’s modern diplomacy as its international relationships and events are. However, there is one major event in Osaka’s modern history yet to be discussed: Expo ’70, which will be examined, along with the upcoming Expo 2025, in the final section.

Osaka’s World Expos of 1970 and 2025

International expositions, also known by various names including world’s fairs, have their origins in the British and French national fairs of the 19th century.[85] These events, which combined trade shows with public entertainment and spectacle, resulted in the Great Exhibition, held in London in 1851, now generally regarded as the first international exposition. The fairs became extremely popular in the following decades, but as a result they were inconsistent, with host countries organising them as they saw fit without common rules or styles. Eventually this led to the founding of the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) in 1928 and the creation of a convention to regulate the system of planning and hosting expositions.[86] Several past expositions were retrospectively recognised, going back as far as London’s Great Exhibition, and different categories were established in the following years, including the smaller-scale specialised expos and horticultural expos. World expos, or universal expositions, are currently held at intervals of at least five years, and are the highest-profile category. Osaka’s Expo ’70 and the forthcoming Expo 2025 both belong to this group.

Source: Yamada Shoten https://www.yamada-shoten.com/onlinestore/detail.php?item_id=43060

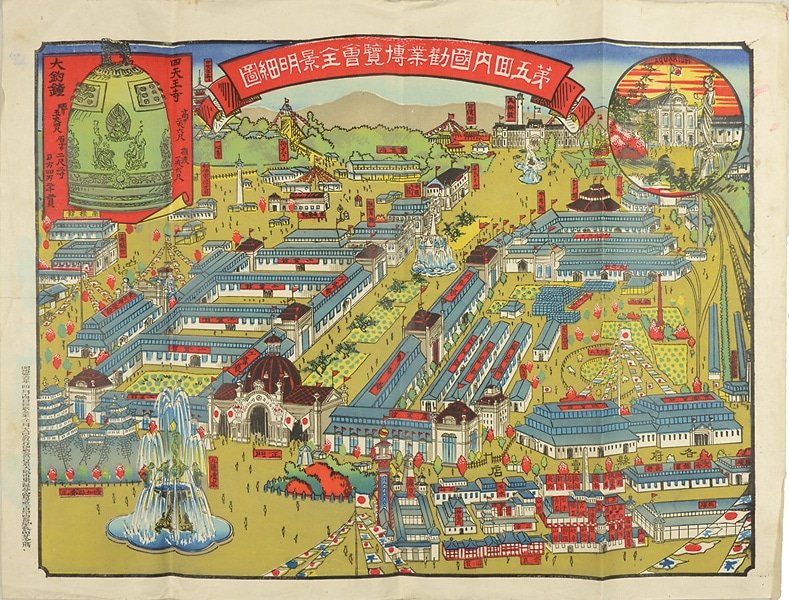

The origins of Osaka’s exposition of 1970 go back to more than a century earlier, to some of the first world’s fairs. The shogun’s military government, along with Japanese regional governments, exhibited at the 1867 event in Paris, and after the Meiji Restoration, the new government had a keen interest in the possibilities for the promotion of industry.[87] The National Industrial Exposition hosted in Osaka in 1903 was, at the time, Japan’s most visited event, primarily aimed at a domestic audience but featuring a number of international guests too. There were plans for a so-called “Great Japan Exposition” to be held in 1912, but the idea did not come to fruition; a world expo was again planned for 1940, which was also abandoned due to the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1958, Osaka City officials began investigating the possibility of hosting an exposition in the southern harbour area, eventually leading to an official bid to the national government in 1964. The Japanese government committed to planning Expo ’70 later that year, only one month after the Tokyo Olympics had concluded, and made its bid to the BIE in 1965.[88] Several Japanese cities competed to be chosen as the host for the event, including others in the Kansai area.[89] Thanks to the 1963 Kinki Region Development Law, eight prefectures in Kansai were able to plan together, and combined their bids into one, eventually choosing the Senri area north of Osaka City as the site for the exposition. There was a strong emphasis on promoting the region, particularly as an alternative to Tokyo, seen for example in local representatives seeking to prioritise architects and other specialists from Kansai; however, this did not prevent the central government from providing extensive support for the project and stressing national unity before and during the event itself.

The scale of Expo ’70 was impressive. The governments of over seventy states and international organisations such as the UN were invited to participate, making the exposition similar to the Tokyo Olympics as an opportunity for Japan to reassert itself in the global community. This internationalist attitude was also reflected in the exposition’s official theme of “Progress and Harmony for Mankind”, under which there were four sub-themes aimed at mutual understanding and improvement of everyday life.[90] One of the event’s most enduring symbols, designed to express the theme, was the Tower of the Sun.[91] Designed by the artist Okamoto Taro, the Tower of the Sun is an intriguing seventy-metre structure showing three faces that symbolise the past, present and future, in addition to a fourth “Underground Sun” face which was displayed in the museum inside the tower, but was later removed. The concepts of chaos and of early human life were also incorporated in the museum, contradicting the theme of “progress and harmony” as a means of expressing Okamoto’s ambivalence towards collaborating on a state-run project; this was also shown in the way that the tower was designed to seemingly burst through the roof of the Symbol Zone.[92] The Symbol Zone was the focal point of the park’s design, which was planned by Osaka-born architects Tange Kenzo – who had previously designed the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and arenas used in the Tokyo Olympics – and Nishiyama Uzo.[93] There was apparently some tension between these two, due to their differing backgrounds: whereas Tange, the designer of several national monuments, was perceived as a government-aligned technocrat, Nishiyama was a Kyoto University professor concerned with more socially-minded issues such as public housing. Nevertheless, they were both influential on other Japanese architects, with Tange especially playing an important role in Metabolism, an experimental movement known for the design of futuristic megastructures incorporating organic forms.[94] Expo ’70, on which many of these architects worked, was one of the biggest displays of Metabolist concepts, and that aesthetic was important to the site’s overall design.

Source: Tower of the Sun Museum https://taiyounotou-expo70.jp/en/about/expo70/

The event was huge not only in terms of physical expanse, however. The number of visitors attending the exposition during its run between March and September 1970 shattered previous records – though the official figure of over 64 million is most likely skewed by great numbers of repeat attendees – and went unmatched until Shanghai’s Expo 2010.[95] Guests including heads of state and other foreign dignitaries visited, as did the Japanese imperial family. Expo ’70 was extremely popular, not surprisingly as it was host to over one hundred pavilions from many nations, organisations and companies. Among the most well-visited pavilions were Japan’s own, as well as the US and Soviet exhibits.[96] Cold War rivalries were on display, with guests having the opportunity to view dramatically exhibited model spacecraft in the Soviet pavilion, and a genuine moon rock in the American one.[97] Besides the specific exhibits, the exposition was also exciting for the Japanese public in a more general sense, as an opportunity to experience the world beyond Japan. The country’s economic revival was still a work in progress at the time, so foreign travel remained prohibitively expensive for most people. Therefore, the chance to meet people and experience culture from other countries was a major draw which left a significant impression on the many attendees.

On the other hand, Expo ’70 was by no means without its detractors. Distrust of the government was fairly widespread at the time, with anti-nuclear and anti-war movements gaining steam, especially in the context of Japan’s role as an ally of the US during the Vietnam War.[98] The exposition specifically came under criticism in its planning stages over concerns about the cost, forced land acquisition for the site, pollution and other issues. Ideologically, there was scepticism about the ostensibly internationalist theme and a belief that the event advanced a nationalist perspective. Meanwhile, when the government sought out avant-garde artists – including the Metabolists – to plan the event space, there were of course a number who could not resist the opportunity to actualise their most spectacular ideas, but there was also a major backlash from others.[99] Many felt that the co-option of experimental artists by the government for the sake of national spectacle was harmful to culture, even to the point of organising protest groups in opposition to Expo ’70. However, artists like Okamoto Taro were aware of these criticisms and sought to challenge nationalist or commercialist ideologies through their own work. Also important was the “Thinking the Expo” group, a study group founded in 1964 to consider the potential value of the exposition. Members of the group would soon be consulted in the project’s planning, where they helped influence the selection of the theme and the commissioning of artists.[100] They were obviously more optimistic about the exposition than the critics, but they too had reservations, such as when aspects of their ideas were actively supressed. Komatsu Sakyo, a member of the group who became well-known as a science fiction author, also raised concerns about the lasting environmental impact of events like Expo ’70, long before such ideas were widely discussed. Views like Komatsu’s, Okamoto’s and others demonstrate that opinions on Expo ’70 were more nuanced than simply “for” and “against”.

Though the event faced criticism for various reason, it had a major immediate impact and has had a lasting legacy. The majority of the buildings used in 1970 were soon demolished, but the site itself remains as the Expo ’70 Commemorative Park.[101] One of the attractions that was closed sooner after the event was even reopened after two years due to its popularity: this was the amusement park Expoland.[102] One of the most exciting draws for locals at the time of the exposition – many years before big-name theme parks like Disneyland and Universal Studios reached Japan – Expoland was next to the main park, and after its reopening, it continued operation for decades. However, in 2007 a student died in a derailment accident on one of the rides, prompting a brief closure, after which the park struggled to make money, resulting in it being permanently closed soon afterwards. Though Expoland is no more, the exposition’s main park is still open and hosts regular events, while the Tower of the Sun has outlived most of the park’s other attractions to become a popular symbol of Osaka and of nostalgia for that time in Japan’s history. After being neglected for some time, the tower was refurbished and the inside was opened to the public sporadically, until it was opened permanently in 2018.[103] Besides the park itself, developments put in place for the exposition such as the Osaka Monorail helped to connect the area to Osaka City, and today Suita is very much urbanised. Expo ’70’s legacy is also reflected in the Japan World Exposition 1970 Commemorative Fund (JEC Fund), which aims to carry on the theme of “Progress and Harmony for Mankind” by using part of the proceeds from the exposition to offer grants to projects involving international cultural exchange, science, conservation and other causes.[104]

The legacy of the exposition is also clear to see when looking at one of the recurring approaches for revitalising Osaka in more recent years: staging similar large-scale events. Most notably, twenty years after Expo ’70, Osaka was host to a BIE-recognised Horticultural Expo.[105] For this exposition, based around the idea of promoting environmental issues, a former industrial site and waste dump in eastern Osaka City was transformed into Tsurumi-Ryokuchi Park. Around 23 million visitors attended, once again including high-profile international guests, and eighty-three countries participated in the event, setting a record for Horticultural Expos. Of the forty-four national gardens built for the exposition, many of the structures remain in the park today, but perhaps appropriately given the environmentalist theme, the manmade parts are largely in disrepair, allowing plant life to take over.[106] Like the JEC Fund founded after Expo ’70, the Horticultural Expo was followed by the establishment of the Expo ’90 Foundation, which provides grants and subsidies to research and cooperative projects, organises international exchange programmes and runs the International Cosmos Prize.[107] The prospect of repeating the success of the two expositions was raised again a few years later, with Osaka beating Yokohama to become Japan’s candidate for the 2008 Summer Olympic Games.[108] Osaka’s Olympic plan featured ideas such as extensive use of artificial islands in Osaka Bay and theming Osaka’s many shopping arcade streets after participating countries.[109] The plan received criticism from multiple angles, particularly cost, which was also cited as a concern by the International Olympic Committee, together with issues regarding transport.[110] Though Osaka’s bid made it as far as the official shortlist, once it reached that stage it lost in the first stage of voting, where Beijing came out victorious.

While the Olympic bid ultimately failed, the idea of using major events to revive Osaka on the global stage evidently can never go away for long. In 2014, Osaka Ishin no Kai, the regionalist party that has dominated Osaka politics in the 2010s, proposed making a bid for Osaka to host another World Expo in 2025.[111] Under the theme of “Designing Future Society for Our Lives”, the bid was formally announced to the BIE in 2017, closely after updating the name to the Osaka Kansai Expo in response to central government fears that Osaka alone lacked the recognition to compete with Paris, another of the 2025 bidders. However, the bid from Paris – also set to host the Rugby World Cup and Olympic Games in the years directly before the 2025 Expo – was soon abandoned due to budgetary issues, leaving Osaka as the frontrunner.[112] Finally, Osaka was chosen as the host for the exposition in a vote of BIE member states in November 2018, overcoming bids from the Russian city of Ekaterinburg and Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan.[113]

Source: Financial Times https://www.ft.com/content/14fb8242-89f0-4090-b67e-deea4c918b2b

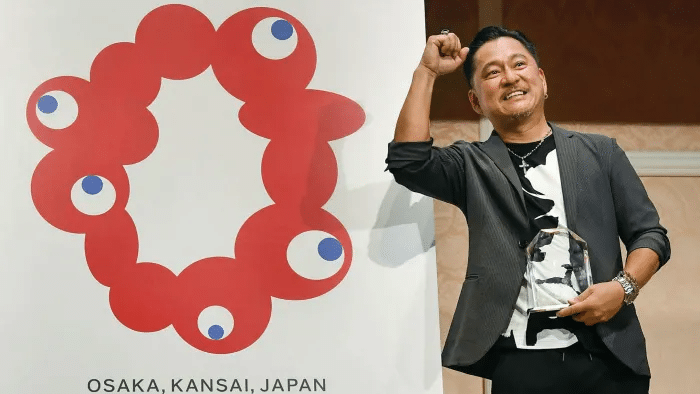

The 2025 exposition is due to be held between April and October, with the site to be built on Yumeshima, the artificial island that was slated to be home to the Olympic Village in 2008. Plans for the exposition emphasise technology, making use of robotics and artificial intelligence to expound upon the theme of “Designing Future Society for Our Lives”, as well as employing a futuristic style in the site’s design.[114] The official logo was designed by local artist Shimada Tamotsu to convey the “brilliance of life”, and was selected from a pool of thousands in a competition.[115] Consisting of a ring of twelve uneven red ellipses with five eyes, roughly in the shape of Osaka City’s borders, the logo, which was partially inspired by the strange quality of the Tower of the Sun, made an immediate impact and has been said to reflect Osaka’s tendency to stand out from the rest of Japan. In practical terms, the event will require additional infrastructure, because although attendance numbers for World Expos have been in decline since Shanghai’s record-breaking figure in 2010, many millions are still expected to visit. Planned improvements include an extension to the Osaka Metro Chuo line between Cosmo Square Station and a new Yumeshima Station that will consist of a skyscraper matching the exposition’s futuristic aesthetic.[116] The lack of a subway connection was an early point of concern for critics of the Expo plans, in addition to worries over funding and a possible clash with the establishment of a casino on Yumeshima.[117] Expo 2025 has also faced criticism in much the same way as the 1970 event, with activists arguing that it is a waste of public money and a distraction from more pressing social issues.[118] Furthermore, at a time when international travel is relatively inexpensive, foreign culture easy to come by, and entertainment and spectacle available in places like Universal Studios Japan, holding a World Expo simply is not the enticing prospect it was in the 1960s. The organisers of the event and various collaborators will therefore need to work hard between now and 2025 to address these concerns and make a success of the exposition.

Summary and Conclusions

In early Japanese history, the Osaka area was at the centre of politics, and due to its strategic location, this extended to foreign diplomacy too. Early port towns like Suminoe-no-tsu and Naniwa-zu helped to connect ancient Japan with continental Asia, especially when Naniwa-zu was made into the nation’s capital. It soon lost its influence, however, and although it still had diplomatic value, the town gradually disappeared, leaving the area fairly quiet until the growth of Sakai in the mediaeval era. Sakai and later Osaka developed as significant port towns, but their importance to foreign diplomacy was curtailed by the restrictions soon placed on international exchange in general. The area was at the centre of clashes with the Western world as the sakoku period came to an end, and soon the modern era brought growing cosmopolitanism to Osaka in various forms. Today, with the capital being far away in Tokyo, official state diplomacy tends not to involve Osaka, but the city is home to many consulates, maintains relationships with cities around the world and has hosted a number of high-profile international events including the famous Expo ’70.

Looking at the future, multiculturalism is sure to increase. Osaka already has many foreign residents and visitors, and international travel has become easier. This brings with it challenges, for example in the need for greater sensitivity over international issues: failure to communicate well can damage relationships, as in the recent incident between Osaka and San Francisco. At the same time, the city faces other problems, which local leaders have often sought to tackle by staging large-scale events, a tactic critics derisively call “festival economics”. At face value, hosting international events like expositions or Olympics seems beneficial for both increasing recognition of Osaka and for improving healthy coexistence between people of many national or ethnic backgrounds. However, they also come with costs – financial and otherwise – which should be carefully considered. Therefore, for the upcoming Expo 2025 to have diplomatic value and to be fondly remembered in the same way as Expo ’70, it must be a success not only for Osaka, but also beyond.

Except where otherwise noted, graphics are by Rachel Stewart (https://www.rachelstewartphd.com/) and other images are photographs taken by the author.

[1] Official Statistics of Japan Foreign Resident Statistics.

[2] ‘History of Nagasaki’. Nagasaki Prefecture Convention and Tourism Association.

https://www.discover-nagasaki.com/History/

[3] 2015. ‘A Brief History of Nagasaki: The Emergence of Christianity and its Role’. Japan Info.

[4] ‘The City of Edo & Edo Castle’. Tokyo Metropolitan Library.

https://www.library.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/portals/0/edo/tokyo_library/english/edojoh/page1-1.html

[5] ‘Yamato Period (250 – 710)’. University of Pittsburgh.

https://www.japanpitt.pitt.edu/timeline/yamato-period-250-710

[6] ‘Excerpts from History of the Kingdom of Wei (Wei zhi)’. Columbia University.

http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/japan/wei_history_wa_pimiko.pdf

[7] ‘Three Kingdoms and other States’. Korean Culture and Information Service.

http://www.korea.net/AboutKorea/History/Three-Kingdoms-other-States

[8] Fuqua, D. ‘The Japanese Missions to Tang China, 7th-9th Centuries’. Japan Society.

https://aboutjapan.japansociety.org/the_japanese_missions_to_tang_china_7th-9th_centuries

[9] Park, H, 2007. ‘Baekje’s Relationship with Japan in the 6th Century’. International Journal of Korean History.

https://ijkh.khistory.org/upload/pdf/11-05.pdf

[10] Tsin, M. ‘Timeline of Chinese History and Dynasties’. Columbia University.

http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/timelines/china_timeline.htm

[11] ‘Sumiyoshi Taisha’. Japan Guide.

https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e4007.html

[12] ‘Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine’. Temples and Shrines of Kansai.

https://konicyan13.sakura.ne.jp/sumiyositaisya4.html

[13] Sakaehara, T, 2008. ‘The port of Osaka: From ancient times to today’. In: Graf, A and Huat, CB, ed. Port Cities in Asia and Europe. Routledge.

[14] 2019. ‘Beautification of the Yodogawa River Landscape’. Osaka Prefecture official website.

http://www.pref.osaka.lg.jp/attach/34342/00319640/yodogawa_English%20P1-P11.pdf

[15] Black, J, 2017. ‘Osaka Ports and Shipping – Institutions and Organisations from Ancient Times to the Meiji Restoration’. University of Oxford.

https://www.tsu.ox.ac.uk/events/170214.pdf

[16] ‘Koraibashi Bridge’. Osaka Convention & Tourism Bureau.

https://osaka-info.jp/en/page/koraibashi-bridge

[17] G.L.M., 2015. ‘Shitennoji Temple’. Japan Experience.

https://www.japan-experience.com/city-osaka/shitennoji-temple

[18] 2006. ‘World’s oldest company, started by Koreans, goes kaput’. Hankyoreh.

http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_international/148711.html

[19] Frydman, J, 2019. ‘Unearthing Lost Memories: A Reexamination of the Role of Naniwa in Early Japan’. Monumenta Nipponica.

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/734129/pdf

[20] ‘Nintoku, Emperor’. University of Pittsburgh.

https://www.japanpitt.pitt.edu/glossary/nintoku-emperor

[21] 2014. ‘Special Exhibition “Historical Heritage of Osaka, the Naniwa Palace Site: Exploring ancient mysteries through some keywords”’. Osaka Museum of History.

http://www.mus-his.city.osaka.jp/eng/exhibitions/special/2014/osakaisan.html

[22] Green, R, 2003. ‘Kukai, founder of Japanese Shingon Buddhism: portraits of his life’. University of Wisconsin.

[23] Tsukada, T and Yagi, S, 2020. ‘Early Modern Osaka from the Documents: The Urban History of Osaka’. Osaka City University.

https://www.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/MSGEM/research/early-modern-osaka-from-the-documents-1/

[24] ‘Watanabe no Tsu (Watanabe Port)’. Japanese Wiki Corpus.

https://japanese-wiki-corpus.github.io/geographical/Watanabe%20no%20Tsu%20(Watanabe%20Port).html

[25] Cartwright, M, 2019. ‘Kamakura Period’. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

https://www.ancient.eu/Kamakura_Period/

[26] ‘Sakoku (Closure of Country)’. National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies.

https://www.grips.ac.jp/teacher/oono/hp/docu03/sakoku.pdf

[27] Kawazoe, S, 1990. ‘Japan and East Asia’. In: Yamamura, K, ed. The Cambridge History of Japan Volume 3: Medieval Japan. Cambridge University Press.

[28] ‘Kamakura period’. Encyclopædia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/event/Kamakura-period

[29] Pearson, R, 2016. ‘Japanese medieval trading towns: Sakai and Tosaminato’. Japanese Journal of Archaeology.

http://www.jjarchaeology.jp/contents/pdf/vol003/3-2_089-116.pdf

[30] ‘Parks’. Sakai City official website.

https://www.city.sakai.lg.jp/smph/english/visitors/enjoying/sightseeing/parks.html

[31] Oka, M, 2017. ‘The Nanban and Shuinsen Trade in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Japan’. In: Garcia, M and De Sousa, L, ed. Global History and New Polycentric Approaches. Palgrave.

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-4053-5_8

[32] Nejime, K, 2014. ‘Alessandro Valignano (1539-1606) between Padua and Japan’. Gakushuin Women’s College.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/292914417.pdf

[33] Kawai, A, 2020. ‘Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Japan: Taking Control of the State’. Nippon.com.

https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/b06906/

[34] Hur, N, 2019. ‘Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s effort of retreat and the ending of the East Asian War’. Chinese Studies in History.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00094633.2019.1606652

[35] Kawai, A, 2020. ‘Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Founding of the Edo Shogunate’. Nippon.com.

https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/b06907/

[36] Toby, R, 1977. ‘Reopening the Question of Sakoku: Diplomacy in the Legitimation of the Tokugawa Bakufu’. The Journal of Japanese Studies.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/132115

[37] McCune, G, 1946. ‘The Exchange of Envoys between Korea and Japan During the Tokugawa Period’. The Far Eastern Quarterly.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2049052

[38] ‘Korean Embassies to Edo’. The Samurai Archives.

https://wiki.samurai-archives.com/index.php?title=Korean_embassies_to_Edo

[39] Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, D, 2010. Russian Orientalism: Asia in the Russian Mind from Peter the Great to the Emigration. Yale University Press.

[40] Ikuta, M, 2008. ‘Changing Japan-Russian Images in the Edo Period’. In: Mikhailova, Y and Steele, M, ed. Japan and Russia: Three centuries of mutual images. Global Oriental.

[41] Lim, S, 2013. China and Japan in the Russian Imagination, 1685-1922: To the Ends of the Orient. Routledge.

[42] 2018. ‘Bakumatsu 150th Anniversary’. Osaka Castle official website.

https://www.osakacastle.net/bakumatsu_ishin150/about_en

[43] Pampling, G, 2018. ‘An audience with the Shogun’. Far Beyond the Miyako.

[44] Ruxton, I, 1994. ‘The Kobe Incident: An Investigation of the Incident and Its Place in Meiji History’. The Japan Association of Comparative Culture.

[45] ‘The Sakai Incident’. Japanese Wiki Corpus.

https://japanese-wiki-corpus.github.io/history/The%20Sakai%20Incident.html

[46] Röpke, I, 1999. ‘Kawaguchi foreign settlement’. In: Historical Dictionary of Osaka and Kyoto. Scarecrow Press.

[47] ‘Japanese consulates – excl. Yokohama’. Room for Diplomacy.

https://roomfordiplomacy.com/japanese-consulates-excluding-yokohama/

[48] ‘Foreign Settlements’. Japanese Wiki Corpus.

https://japanese-wiki-corpus.github.io/history/Foreign%20Settlements.html

[49] ‘Kawaguchi Foreign Concession’. Momoyama Gakuin University.

https://www.andrew.ac.jp/nenshi/concession_p1.htm

[50] ‘Landmarks and Historic Locations’. Osaka City Nishi Ward official website.

https://www.city.osaka.lg.jp/contents/wdu020/nishi/english/spot_01.html

[51] Kamibayashi, Y, 1999. ‘The Background of G.A. Escher, Hollander Engineer who supported J. de Rijke for 40 years’. Japan Society of Civil Engineers.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/journalhs1990/19/0/19_0_399/_pdf

[52] Johnston, E, 2017. ‘Lessons learned from the failure of the Osaka Foreign Settlement’. The Japan Times.

[53] Johnston, E, 2017. ‘Taking a look back at Kobe’s opening to the West nearly 150 years ago’. The Japan Times.

[54] ‘The History of Momoyama’. Momoyama Gakuin University official website.

https://www.andrew.ac.jp/english/history/index.html

[55] Yamamoto, T. ‘Summary’. Kawaguchi Foreign Settlement Research Society.

https://takakoym4112289.wixsite.com/kawaguchi

[56] Burke-Gaffney, B and Earns, L, 2017. ‘Life and Work in the Nagasaki Foreign Settlement, 1859-1899’. Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science.

http://www.nfs.nias.ac.jp/page003.html

[57] 2020. ‘Foreign Missions in Japan’. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

https://www.mofa.go.jp/about/emb_cons/protocol/index.html

[58] 2011. ‘Promotion of intenationalisation in Kobe City: reference data’. Kobe City official website.

https://www.city.kobe.lg.jp/information/project/taikousannkousiryou.pdf

[59] ‘History of the German Consulate General’. German Embassy in Japan official website.

https://japan.diplo.de/ja-ja/vertretungen/gk/geschichte/979962

[60] Arita, E, 2009. ‘Christmas market in Osaka serves festive German treats’. The Japan Times.

[61] ‘Brief history of the consulate general’. Korean Consulate General in Osaka official website.

http://overseas.mofa.go.kr/jp-osaka-ja/wpge/m_801/contents.do

[62] Mun, G, 2009. ‘Origins of the Current Problems of Korean Residents in Japan’. Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies.

https://kias.asafas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/1st_period/contents/pdf/kb3_1/13mun.pdf

[63] Park, J, 2018. ‘Koreans living in Japan without nationality’. The Korea Times.

https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2018/06/103_250233.html

[64] 2004. ‘Chronology for Koreans in Japan’. Minorities at Risk Project.

https://www.refworld.org/docid/469f38aac.html

[65] Rosen, A, 2012. ‘The Strange Rise and Fall of North Korea’s Business Empire in Japan’. The Atlantic.

[66] Kokita, K, Morris-Suzuki, T and Selden, M, 2011. ‘Ko Tae Mun, Ko Chung Hee, and the Osaka Family Origins of North Korean Successor Kim Jong Un (with commentary)’. The Asia-Pacific Journal.

https://apjjf.org/2011/9/1/Mark-Selden/3465/article.html

[67] ‘Regional maps’. Chongryon official website.

http://www.chongryon.com/j/cr/map/map_5_kinki.html

[68] 2017. ‘Pyongyang slams Osaka court ruling rejecting subsidies for Chongryon-backed schools’. The Japan Times.

[69] Tai, E, 2007. ‘Multicultural Education in Japan’. The Asia-Pacific Journal.

https://apjjf.org/-Eika-TAI/2618/article.pdf

[70] ‘The City of Osaka’s International Network’. Osaka City official website.

https://www.city.osaka.lg.jp/contents/wdu020/keizaisenryaku/english/international_network.html

[71] ‘Sister City Information: Osaka Prefecture’. Council of Local Authorities for International Relations.

http://www.clair.or.jp/e/exchange/shimai/prefectures/detail/27

[72] Oda, M, 2017. ‘Masculinizing Japan and Reorienting San Francisco: The Osaka-San Francisco Sister-City Affiliation During the Early Cold War’. Diplomatic History.

https://academic.oup.com/dh/article/41/3/460/2649136

[73] 2017. ‘60th San Francisco Delegation visits Osaka’. San Francisco-Osaka Sister City Association.

https://www.sf-osaka.org/single-post/2017/10/29/60th-San-Francisco-Delegation-visits-Osaka

[74] McCurry, J, 2018. ‘Osaka drops San Francisco as sister city over “comfort woman” statue’. The Guardian.

[75] Carey, J, 2019. ‘What Happens When Sister Cities Break Up?’ Atlas Obscura.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/what-happens-when-sister-cities-break-up

[76] ‘Shanghai Office’. Osaka Prefecture Shanghai Office official website.

http://osaka-sh.com.cn/shanghai-office/

[77] Iguchi, J, 2013. ‘Osaka and Shanghai: Revisiting the Reception of Western Music in Metropolitan Japan’. In: Tokita, A, de Ferranti, H and Howard, K, ed. Music, Modernity and Locality in Prewar Japan: Osaka and Beyond. Taylor & Francis.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ed/detail.action?docID=1250107

[78] ‘World Expos Since 1851’. Bureau International des Expositions.

https://www.bie-paris.org/site/en/all-world-expos

[79] 2007. ‘Secretary-General Appoints Kiyotaka Akasaka of Japan Under-Secretary-General for Communications and Public Information’. United Nations official website.

https://www.un.org/press/en/2007/sga1041.doc.htm

[80] ‘1995 APEC Ministerial Meeting’. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

https://www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Annual-Ministerial-Meetings/1995/1995_amm

[81] Drysdale, P, 1998. ‘Japan’s approach to Asia Pacific economic cooperation’. Journal of Asian Economics.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1049007898900628

[82] ‘Summit Venue’. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/g20_summit/osaka19/en/summit/osaka/

[83] Hurst, D, 2019. ‘Did Japan Get What It Wanted From the Osaka G20 Summit?’ The Diplomat.

https://thediplomat.com/2019/07/did-japan-get-what-it-wanted-from-the-osaka-g20-summit/

[84] Johnston, E, 2019. ‘Osaka braces for unprecedented security measures ahead of G20 summit’. The Japan Times.

[85] Findling, J. ‘World’s fair’. Encyclopædia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/worlds-fair

[86] ‘Our History’. Bureau International des Expositions.

https://www.bie-paris.org/site/en/about-the-bie/our-history

[87] Hashizume, S, 2020. ‘Expo 1970 Osaka: the story of Japan’s first World Expo’. Bureau International des Expositions.

https://www.bie-paris.org/site/en/focus/entry/expo-1970-osaka-the-story-of-japan-s-first-world-expo

[88] Wilson, S, 2011. ‘Exhibiting a new Japan: the Tokyo Olympics of 1964 and Expo ’70 in Osaka’. Institute of Historical Research.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-2281.2010.00568.x

[89] Flores Urushima, A, 2011. ‘The 1970 Osaka Expo: local planners, national planning processes and Mega Events’. Planning Perspectives.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02665433.2011.599933

[90] ‘Expo 1970 Osaka’. Bureau International des Expositions.

https://www.bie-paris.org/site/en/1970-osaka

[91] ‘About the Tower of the Sun Museum’. Tower of the Sun Museum official website.

https://taiyounotou-expo70.jp/en/about/

[92] Winther-Tamaki, B, 2011. ‘To Put On A Big Face: The Globalist Stance of Okamoto Taro’s Tower of the Sun for the Japan World Exposition’. Review of Japanese Culture and Society.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/42801089

[93] Cho, H, 2011. ‘Expo ’70: The Model City of an Information Society’. Review of Japanese Culture and Society.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/42801087

[94] Angelidou, I and Yatsuka, H, 2012. ‘Metabolism and After: A Correspondence With Hajime Yatsuka’. Architecture Criticism.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41765464

[95] Johnston, E, 2020. ‘The 1970 Osaka Expo: Looking back at the past to gauge where Japan sits in the present’. The Japan Times.

[96] Shabecoff, P, 1970. ‘Moon Rock Fascinates Osaka Crowd’. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/1970/03/16/archives/moon-rock-fascinates-osaka-crowd.html

[97] Gray, B, 2020. ‘When Apollo Went to Japan’. Air & Space Magazine.

https://www.airspacemag.com/space/when-apollo-went-japan-180974469/

[98] Borggreen, G, 2006. ‘Ruins of the Future: Yanobe Kenji Revisits Expo ’70’. Performance Paradigm.

http://www.performanceparadigm.net/wp-content/uploads/2007/06/10borggreen.pdf

[99] Yoshimoto, M, 2011. ‘Expo ’70 and Japanese Art: Dissonant Voices. An Introduction and Commentary’. Review of Japanese Culture and Society.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/42801083

[100] Gardner, W, 2011. ‘The 1970 Osaka Expo and/as Science Fiction’. Review of Japanese Culture and Society.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/42801085

[101] Stephens, C, 2017. ‘The Future Is the Past at Expo ’70 Pavilion’. Artscape Japan.

http://www.dnp.co.jp/artscape/eng/focus/1706_02.html

[102] Seidel, F, 2010. ‘Expoland’. Abandoned Kansai.

https://abandonedkansai.com/2010/06/14/expoland/

[103] Grundhauser, E, 2018. ‘Tower of the Sun’. Atlas Obscura.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/tower-of-the-sun

[104] ‘What is the Japan World Exposition 1970 Commemorative Fund?’ JEC Fund official website.

https://www.osaka21.or.jp/jecfund/about/

[105] ‘Expo 1990 Osaka’. Bureau International des Expositions.

https://www.bie-paris.org/site/en/1990-osaka

[106] ‘International Garden’. Tsurumi-Ryokuchi Park official website.

https://www.tsurumi-ryokuchi.jp/guide/kokusaiteien.html

[107] ‘About Us’. Expo ’90 Foundation official website.

https://www.expo-cosmos.or.jp/english/about/

[108] 1997. ‘Osaka named candidate for 2008 Olympic Games’. The Japan Times.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/1997/08/13/national/osaka-named-candidate-for-2008-olympic-games/

[109] 2017. ‘The Olympics in Osaka?’ Kansai Culture.

https://kansaiculture.blogspot.com/2017/01/the-olympics-in-osaka-japan-is.html

[110] 2001. ‘Report of the IOC Evaluation Commission for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad in 2008’. International Olympic Committee.

https://stillmed.olympic.org/Documents/Reports/EN/en_report_299.pdf

[111] Johnston, E, 2017. ‘Osaka sets sights on 2025 World Expo, but formidable challenges remain’. The Japan Times.

[112] De Clerc, G and Carriat, J, 2018. ‘France drops bid to host 2025 World Expo’. Reuters.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-expo-idUSKBN1FA10U

[113] 2018. ‘Japan elected host country of World Expo 2025’. Bureau International des Expositions.

[114] ‘Expo 2025 Osaka Kansai’. Bureau International des Expositions.

https://www.bie-paris.org/site/en/2025-osaka

[115] Lewis, L, 2020. ‘The strange comfort of a five-eyed monster’. Financial Times.

https://www.ft.com/content/14fb8242-89f0-4090-b67e-deea4c918b2b

[116] 2018. ‘Yumeshima area redevelopment to feature boldly designed new station, skyscraper for Osaka World Expo 2025’. Japan Trends.

https://www.japantrends.com/yumeshima-area-redevelopment-new-station-skyscraper-osaka-expo-2025/

[117] Johnston, E, 2018. ‘As Osaka basks in glow of successful 2025 Expo bid, economic concerns move to the forefront’. The Japan Times.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/11/24/national/osaka-host-2025-world-expo/

[118] Andrews, W, 2019. ‘Preparations for Osaka 2025 World Expo spark local opposition and protests’. Throw Out Your Books.

https://throwoutyourbooks.wordpress.com/2019/01/21/osaka-2025-world-expo-local-protests-opposition/