Where can you go if you’ve already visited most of Osaka’s main tourist attractions – or you just want a bit of a break from the big city? Luckily there are many more places to go outside of the city, but still within easy reach of Osaka. This article is the second in a series looking at these places, which began last time with Ikeda. Today we’re looking at Sakai, Osaka Prefecture’s second-largest city.

Table of Contents

Why you should go to Sakai

Sakai is directly south of Osaka City, and is connected by major railway lines including Nankai and the Osaka Metro. Historically it has often been one of Japan’s main ports, and even today it is one of the 20 most populous cities in Japan, making Sakai more urbanised than some other parts of Osaka Prefecture. Today, I’ll go into some detail about Sakai’s long history and share some of the best places to walk around and see the city, taking in ancient tombs, relaxing parks, museums and more.

The history of Sakai

The Osaka area was important in the early history of Japan as a nation, when it was a marshy region of agriculture and port towns. The national capital was situated where Osaka City is today, perhaps on multiple occasions, with the first time said to have been in the 4th century CE during the reign of the semi-legendary Emperor Nintoku. At that time, members of the ruling class were buried all around Japan in large, keyhole-shaped tombs called kofun. The kofun traditionally regarded as Nintoku’s grave is part of the Mozu-Furuichi group in modern-day Sakai City. This shows just how central the area was at this time in Japanese history.

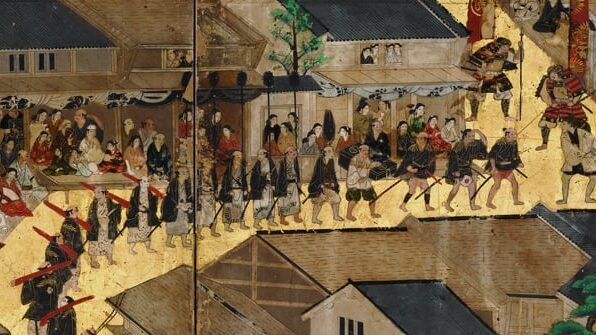

The port town of Sakai was named for its location. The word sakai (堺) means “border”, and the town straddled the boundaries of the three old provinces of Settsu, Izumi and Kawachi. This distinction was significant in the 15th and 16th centuries, when the Sengoku (“warring states”) Period saw an extended period of civil war, and provinces were under the control of local warlords. Sakai, which had become a major port by then, was governed instead by a merchants’ council and was known as a “free city”. This was an important time in Sakai’s history, when it was one of the country’s main sites for international trade and diplomacy (read more about the diplomatic history of Osaka here). Foreign culture was also brought to Sakai by missionaries including Francis Xavier, the first Jesuit missionary to visit Japan. Xavier Park in Sakai, which was named in his honour, can be found on the site of the home of a merchant who supported Xavier and other missionaries.

Sakai has also had an important impact on the history of Osaka City. Towards the end of the Sengoku Period, the samurai warlord Oda Nobunaga was attempting to reunify the country by force. One of the main opposition forces was a Buddhist faction headquartered in Ishiyama Honganji, a temple that the town of Osaka grew around. During his eventually successful war against Ishiyama Honganji, Nobunaga’s forces were based in Sakai, a major producer of arms at that time. These events led to Osaka becoming the political centre of Japan for several years as Nobunaga’s successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, founded Osaka Castle on the former site of Ishiyama Honganji and continued the struggle for unification. Another connection between Sakai and Osaka is in Sakai’s closeness to Sumiyoshi Grand Shrine, which is part of southern Osaka City today but once controlled part of Sakai. A traditional element of the shrine’s summer festival, Sumiyoshi Matsuri, is a procession bringing the mikoshi – a portable shrine transporting a deity – south to Sakai (read more about traditional ceremonies and festivals in Osaka here). Today’s Sakai Matsuri, held in Sakai every October, also reflects this history with a parade and other events including markets selling local specialities.

After the Sengoku Period, Sakai was overtaken by Osaka among the great cities of Japan, but it remained important as a port even around the time Japan’s modern era began. It was still such a major city that when the system of prefectures was first being set up in the late 19th century, Sakai Prefecture was formed out of the old provinces of Izumi and Kawachi. For a short time, even today’s Nara Prefecture was absorbed into Sakai Prefecture, before the boundaries were redrawn again and Sakai joined Osaka Prefecture. Sakai was also the setting for a dramatic episode showing the tension between Japan and the growing influence of foreign powers. In the Sakai Incident, eleven French sailors were killed at the port, triggering a diplomatic crisis where the French authorities demanded that the perpetrators be executed. Twenty were eventually sentenced to public ritual suicide, but after the first eleven, the French captain asked for the last nine to be pardoned. This point in Sakai’s history is also represented by the Old Sakai Lighthouse, which is the oldest remaining wooden lighthouse in the country. It was built in 1877 and was in operation for almost a century before land reclamation changed the city’s coastline. It remains as a popular symbol of Sakai today.

Nowadays, although it is dwarfed by Osaka, Sakai is a large city with over 800,000 residents. Its best-known industries include knives and bicycles, which developed using the technologies that have been used for making swords and firearms for hundreds of years. While Sakai is closely connected with Osaka, its long history of independence can still be seen too. One of the early setbacks for the Osaka Metropolis Plan – a policy that would have restructured Osaka and other nearby cities into a “metropolis” like Tokyo – was a lack of support from Sakai residents, forcing its proponents to scale back the plan (read more about the Osaka Metropolis Plan here). Reasons for opposing the plan included skepticism about its actual benefits, but part of it may also have been an unwillingness to be absorbed into Osaka City after centuries of independence.

You can see Sakai’s history for yourself at several popular sightseeing spots. I will now tell you about a few that you should visit.

The Mozu-Furuichi kofun group

As I mentioned earlier, emperors and other members of the ruling class in ancient Japan were entombed in kofun, large mounds typically in the shape of a keyhole. Hundreds were constructed around Japan between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE, an era often called the Kofun Period. The kofun in the Mozu-Furuichi group are so far the only ones to be recognised as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. These are made up of the Mozu tombs in Sakai and the Furuichi tombs in the neighbouring cities of Habikino and Fujiidera. Some of these kofun are enormous, such as the Daisenryo Kofun, supposedly Emperor Nintoku’s final resting place, which is the largest in the country and one of the largest tombs in the world at nearly 500 metres in length.

The Mozu-Furuichi kofun are easy to visit, but you can only look from the outside. Wide moats surround each of the forested mounds, which have been accessed only occasionally by archaeologists for excavation projects. Even so, they are impressive to see, especially the Daisenryo Kofun, which takes about an hour to walk around and has a picturesque torii gate at its southern end. The keyhole shape can only be seen from an aerial view, but if you go to Sakai City Hall, you can at least get a sense of its size compared with the surrounding area. The city hall’s 21st floor has an observation lobby where you can look out over the Daisenryo Kofun and the urban scenery of Sakai. Whether up-close or from a distance, the Mozu-Furuichi kofun are a fascinating sight.

Daisen Park

Daisen Park is located between several of the largest kofun and includes a few smaller ones itself. Within the park is Sakai City Museum, a museum devoted to the city’s history where you can learn more about the kofun. This is not the park’s only museum, as you can also find Japan’s only bicycle museum here. Bicycle Museum Cycle Center is all about the history of Sakai’s bicycle industry, and exhibits a variety of bicycles of many different kinds. Between them, these museums offer visitors a chance to understand Sakai’s history from ancient to modern times.

The park also features a beautiful Japanese garden, created to celebrate the centenary of the foundation of modern Sakai City. Various seasonal flowers can be seen in the garden, including plum trees which bloom in February, and there are often exhibits of flowers in the main pavilion. As Sakai is important to the history of Japanese tea ceremony – more on that in the next section – matcha and seasonal confectionary are also available in the Japanese garden and in two teahouses elsewhere in the park. Altogether, Daisen Park is a good place to go for a relaxing walk, especially if you are also checking out the Mozu-Furuichi kofun.

Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko

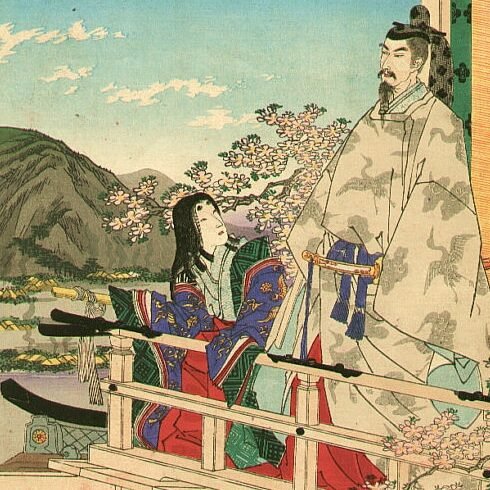

Sen no Rikyu and Yosano Akiko are two of Sakai’s most famous historical figures. The son of a Sakai merchant, Sen no Rikyu was a tea ceremony master who studied the art in Sakai and Kyoto before working under Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, two of the “great unifiers” at the end of the Sengoku Period. He revolutionised tea ceremony with an emphasis on hospitality, rustic aesthetics and equal treatment of guests. Although his friendship with Hideyoshi fell apart, he had a huge influence on the development of Japanese tea ceremony.

Yosano Akiko was also born into a successful merchant family, and became one of the most famous Japanese poets of the early 20th century. As well as controversial works like the collection Tangled Hair (Midaregami) and the anti-war poem Thou Shalt Not Die (Kimi shintamo koto nakare), she wrote about social issues and produced a modern Japanese translation of the classic The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari). Her work also had an impact on the early feminist movement in Japan.

These two figures are celebrated at the Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko. This museum has information about Sen no Rikyu and Yosano Akiko, and their place in Sakai’s history. There are displays of the cover designs for Yosano’s books, a recreation of Rikyu’s last remaining tearoom, and opportunities to participate in a tea ceremony yourself. Through the lives of these famous individuals, the museum teaches visitors about the cultural history of Sakai.

Access

There are several ways to reach Sakai by train. The JR and Nankai networks both have several stations in Sakai, and the Osaka Metro and Hankai tramway also go there. Generally speaking, the Nankai Main Line is useful for areas near the shore, such as the Old Sakai Lighthouse, while the Nankai Koya Line and JR Hanwa Line provide connections to more inland sights like the kofun. Depending on your starting point and the places you want to visit, the most suitable method can vary, but read on for suggestions on the most direct routes from major stations in Osaka.

For the Daisenryo Kofun, the nearest stations are Mikunigaoka and Mozu on the JR Hanwa Line. An adult fare from Tennoji to either station is 220 yen. It takes about 10 minutes on a rapid service train from Tennoji to Mikunigaoka. Mikunigaoka is also on the Namba Koya line. A local train from Namba takes about 30 minutes and costs 340 yen. A faster route is to take an express or sub express train to Sakaihigashi – roughly 10 minutes – and change to a local service there.

Only JR local service trains stop at Mozu, but it is also the nearest station for Daisen Park. You can either take the local train all the way from Tennoji, which takes around 25 minutes, or take a rapid train to Mikunigaoka and change. The fare is still 220 yen.

For the Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko, the nearest station is Shukuin on the Hankai tramway. From either Ebisucho or Tennoji, it takes around 35 minutes and costs 230 yen. Note that if you are going from Ebisucho, you will need to change at Sumiyoshi, and that the Tennoji Hankai stop is outside the main station. Alternatively, the Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko is also about ten minutes’ walk from Sakai Station on the Nankai Main Line. From Namba, express trains take around 10 minutes, local trains take around 15 minutes, and an adult fare is 260 yen.

Entry to Sakai City Museum, Bicycle Museum Cycle Center and the Daisen Park Japanese Garden costs 200 yen each, and entry to the Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko costs 500 yen. Additional fees apply for services like tea ceremonies. There are no fees for visiting the Mozu-Furuichi kofun, Daisen Park or the city hall observation lobby.

Opening hours vary, and please note that at the time of writing (May 2021) many facilities are temporarily closed. Visit the links below to check up-to-date availability and opening hours.

Bicycle Museum Cycle Center (Japanese)

Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko

Except where otherwise noted, images are photographs taken by the author.