It’s no secret that comics and animation are among Japan’s biggest cultural exports today. Manga and anime are both huge industries in Japan and have fans all around the world. For many visitors, they’re an important part of the country’s appeal. Osaka Manga

Tokyo is often seen as the centre of Japanese pop culture, but what about Osaka? This article is the first of two looking at Osaka’s place in the history of manga and anime, and how it is portrayed in Japanese comics and animation. Part 1 focuses on important people and events, from Astro Boy author Tezuka Osamu and gekiga pioneers, to famous Osaka University of Arts alumni and the influence of Expo ’70. Part 2 will cover some common tropes associated with the city and its people, and finally suggest some great places for manga and anime fans to visit in and around Osaka.

Now, let’s take a look at some history, starting with one of the best-known trailblazers in both manga and anime.

Table of Contents

Tezuka Osamu: “the father of manga”

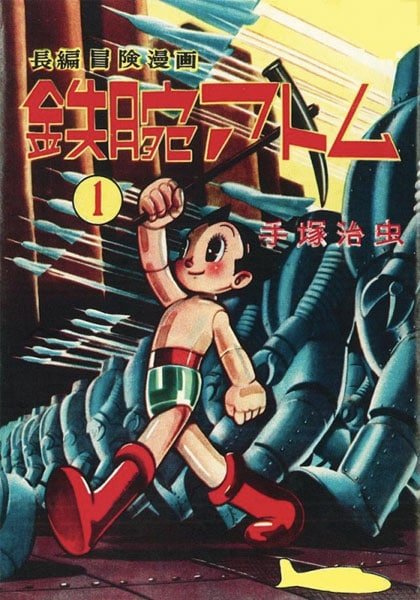

Tezuka Osamu is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of manga. Some of his famous works include Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atomu) and Kimba the White Lion (Janguru Taitei), and he was often involved in producing animated adaptations too. Inspired by American and European cartoons and characters like Mickey Mouse, he developed a visual style that became the template for postwar Japanese comics and animation, including now-standard features like large eyes. He also set the tone for entire genres in works like Princess Knight (Ribon no Kishi), which was influential in shojo manga (comics aimed at girls). Though he spent most of his adult life in Tokyo, where he worked closely with other major manga artists and founded animation studios, Tezuka was actually born and educated in Osaka Prefecture.

Tezuka was born in 1928 in Toyonaka and attended school in Ikeda. Growing up around Osaka at this time had a major impact on Tezuka, as he was a high school student during the bombing campaign on the city in the Second World War. His experience of surviving an air raid at the arsenal near Osaka Castle was especially significant, helping to shape his views on war and peace – ideas that later appeared in many of his works, from science fiction manga like Astro Boy to epic stories like Buddha. While growing up in Osaka, his family home was in neighbouring Takarazuka in Hyogo Prefecture, home of the all-female Takarazuka Revue, which was founded by Hankyu railway entrepreneur Kobayashi Ichizo. The stories and aesthetics of the Revue were another inspiration for Tezuka’s art, particularly in works like Princess Knight.

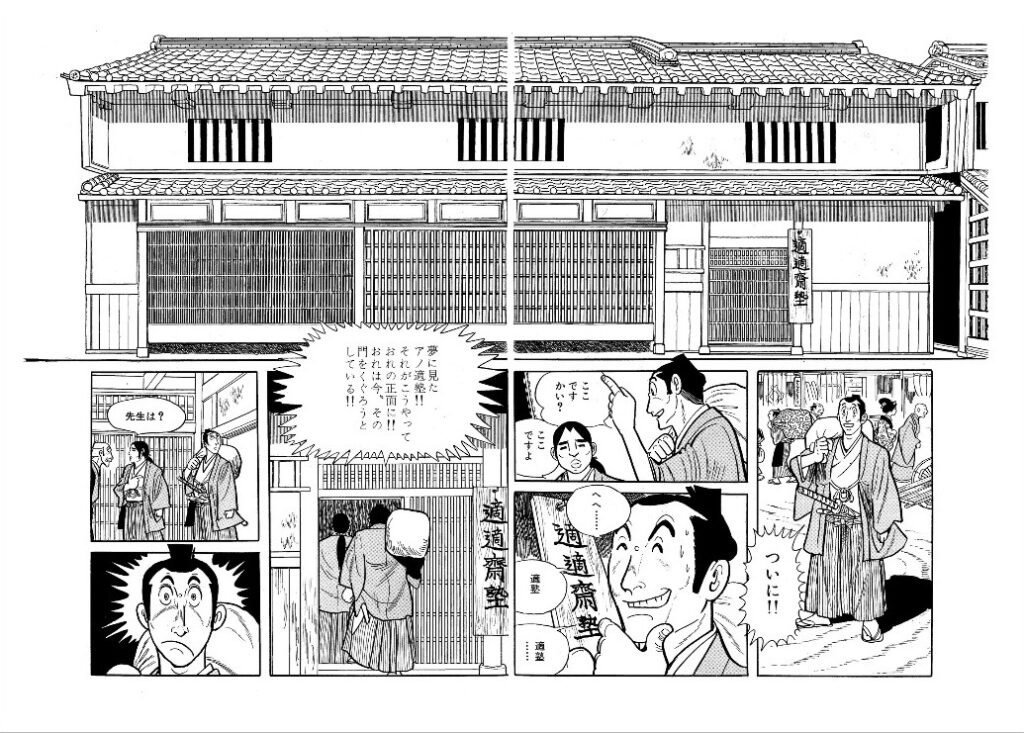

In 1945, Tezuka was accepted into Osaka University. By studying medicine there, he was following in the footsteps of his great-grandfather Ryoan. During the 19th century, Ryoan was a student of medicine and other rangaku (“Dutch studies” or Western science) at Tekijuku, an important institution of higher education which was one of the building blocks of Osaka University. Tezuka was already producing manga while he attended medical school, and decided to prioritise manga over a potential career as a doctor almost as soon as he graduated. His background in medicine still played a part in his work though, in medical-themed stories such as the popular Black Jack and a series inspired by the life of his great-grandfather.

After graduating from Osaka University, Tezuka moved to Tokyo, following the allure of the manga industry. Even so, his childhood in Osaka affected his ideals and his artistic interests in many ways. His pioneering work in various genres would then go on to inspire generations of artists after him, as you will see throughout this article.

The origins of Japanese alternative comics

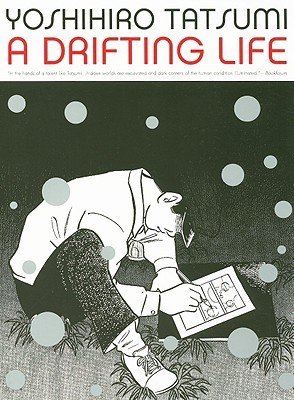

While Tezuka Osamu represents what became the mainstream manga style after the Second World War, there were others who rejected mainstream conventions and even the term “manga”. Tatsumi Yoshihiro, who was born in Osaka in 1935, was determined to make serious, mature comics, leading him to coin the term gekiga in the 1950s. As the name gekiga (literally “dramatic pictures”) suggests, the work of Tatsumi and his colleagues aimed to be more cinematic than other manga. The grittier, more subversive stories they published in magazines like Garo later gave gekiga a reputation as a label for comics with shocking content, but this was not necessarily the goal. More important was aesthetic and narrative realism, resulting in a style that influenced alternative manga writers ever since.

Like many people in manga, Tatsumi Yoshihiro was inspired by Tezuka, one of his early mentors. However, while Tezuka quickly entered the publishing industry of Tokyo, the environment in Osaka was important for Tatsumi. Publishers in Tokyo produced polished, high-quality releases, whereas the old kashi-hon industry of rental books was still central in Osaka, allowing more room for experimentation. During the 1950s, Tatsumi created works for the kashi-hon market, seeking out an audience a little older than mainstream manga, which at the time was aimed mainly at schoolchildren. As he developed the gekiga concept, Tatsumi moved from detective fiction and thrillers to more clearly adult subjects, often portraying people on the fringes of society. Among his most celebrated works today is A Drifting Life (Gekiga Hyoryu), a semi-autobiographical story about Tatsumi’s early career.

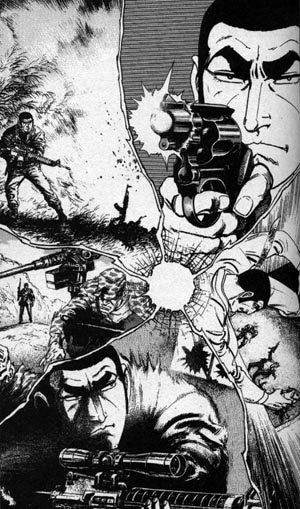

Other early gekiga artists who worked with Tatsumi in Osaka include Matsumoto Masahiko and Saito Takao. One of the founding members of Tatsumi’s short-lived “Gekiga Workshop”, Saito is best known for Golgo 13, a series about a professional assassin which is credited with popularising gekiga. Golgo 13 began in 1968 and is the oldest manga still in publication – a record it will probably maintain, as it’s set to continue being published after the author’s recent passing. Even Tezuka, the “father” of modern mainstream manga, was involved in gekiga. From the late 1960s, he produced works containing more adult themes, and started the magazine COM to compete with Garo in publishing innovative material. This more mature and experimental approach appears in much of his later output, including celebrated works like Phoenix (Hi no Tori).

Leading the way in girls’ manga

Manga covers all kinds of different genres, from comedy and romance to action and horror. It is also often categorised according to the readership of the magazine a series is published in. Manga magazines tend to have clear target demographics, including shonen publications catering mainly to young male readers, and shojo magazines catering mainly to young female readers. Although the actual genre varies, shojo manga is often recognisable for certain story tropes and visual elements. Among the big names who developed the shojo manga style are several Osaka artists.

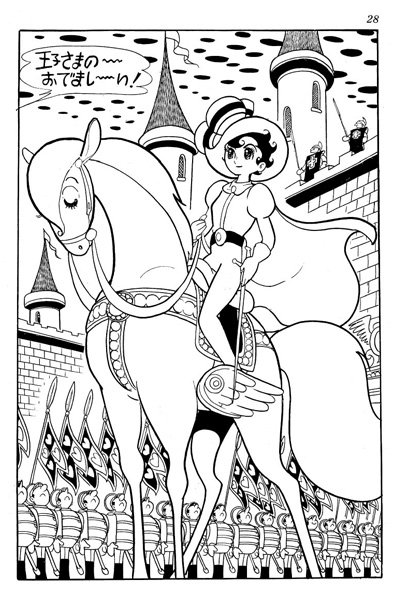

Girls may be the target audience, but a lot of early shojo manga was written by men. Of course, these include Tezuka Osamu, whose Princess Knight was hugely popular. It was groundbreaking as a story-focused shojo series, at a time when light comedy was the standard. Princess Knight also featured elements that would become shojo staples, such as a European fairytale-inspired setting and an androgynous heroine. Another early innovator was Takahashi Macoto. Like Tezuka, Takahashi’s perspective on life was shaped by surviving the bombing of Osaka as a child. His manga work in the 1950s helped to popularise features like big, sparkly eyes in shojo art, and he continued to produce illustrations and designs in the following decades, influencing not only manga and anime but also fashion.

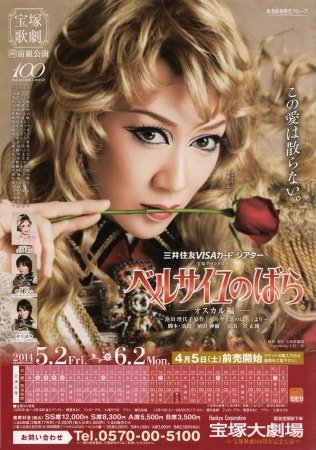

It was only in the early 1970s that female writers became common in shojo manga. Two of the most successful of these were born in Osaka: Ikeda Riyoko and Miuchi Suzue. Associated with the influential “Year 24 Group”, Ikeda has produced many famous works, but her best-known is The Rose of Versailles (Berusaiyu no Bara). In some ways it follows the lead of Princess Knight, with its androgynous protagonist and European backdrop – being set during the French Revolution – but it is more of a serious historical drama dealing with weighty political and social themes. Like Princess Knight, The Rose of Versailles is also closely connected with the Takarazuka Revue, after early musicals based on the manga kicked off a resurgence in the Revue’s popularity and were followed by many more adaptations over the years.

Theatre is also important for Miuchi Suzue, who is famous for writing Glass Mask (Garasu no Kamen), a story about an aspiring stage actress that began in 1975. As the manga is still incomplete, Glass Mask is only a few years behind Golgo 13 for oldest ongoing manga series, and is also one of the all-time bestselling shojo series. Like other popular manga from the 1970s, Miuchi’s art and writing inspired many others in the genre.

Inspirations for science fiction anime

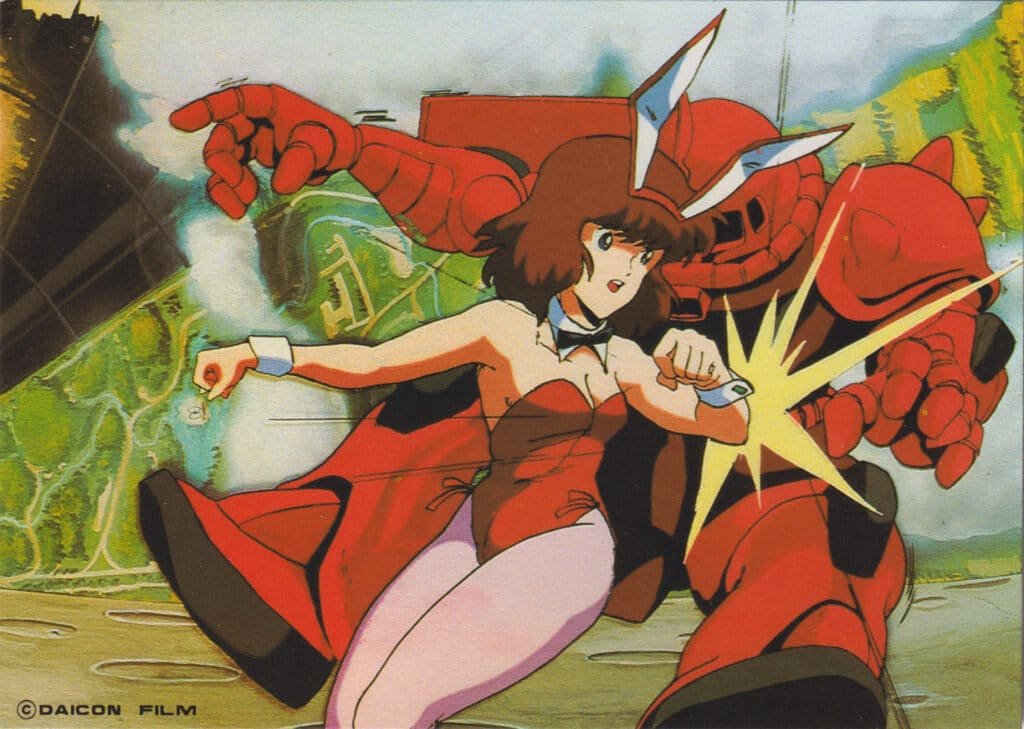

The 20th Japan Sci-fi Convention (Nihon SF Taikai) – also called DAICON III – was held in Osaka in 1981. Takeda Yasuhiro and Okada Toshio, two of the convention’s organisers, had made a name for themselves in local science fiction fan communities, and were eager to put on a show. One part of this was commissioning a fan-made short film, the DAICON III Opening Animation, which was created by Osaka University of Arts students Yamaga Hiroyuki, Akai Takami and Anno Hideaki. The film, which crammed in (unauthorised) shout-outs to popular sci-fi franchises, was a hit, and was followed two years later by another, more complex animation for DAICON IV. These two films were huge among the growing anime fan community, and the people involved went on to enjoy great success in the anime industry.

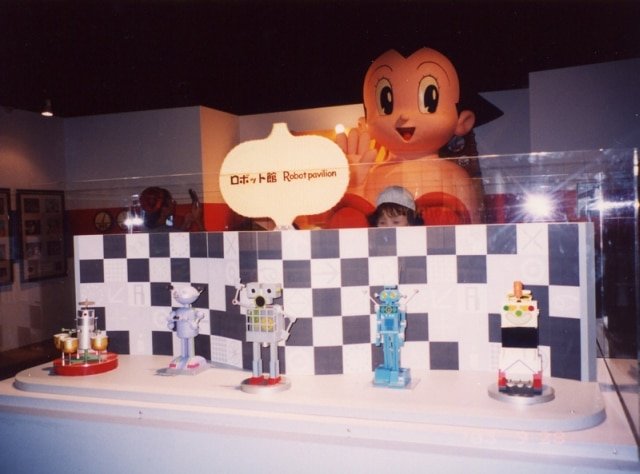

An important inspiration for the DAICON organisers was their experiences of visiting the 1970 World Expo in Osaka. Expo 70‘ was a huge event based on the theme of “Progress and Harmony for Mankind”, with guests from over seventy states and international organisations. There were many futuristic exhibits, including the Fujipan Robot Pavilion featuring designs from none other than Tezuka Osamu. Meanwhile the United States pavilion showed off a genuine moon rock from the Apollo 12 expedition, which Takeda recalled queuing for hours to see. Okada and DAICON III and IV animator Anno also regarded Expo ’70 as a formative experience, and it is easy to imagine how the exposition’s impressive exhibits and otherworldly architecture would affect budding sci-fi fans.

The team that produced the DAICON animations, comprised mainly of Osaka natives Takeda and Okada together with Osaka University of Arts animators, later established the anime studio Gainax. As a studio founded by fans, they were unusual at that time, and they produced many hit series, especially in the sci-fi genre. These included Gunbuster (Toppu o Nerae!) and Evangelion, both directed by Anno, which became major points of reference in anime fandom. Though it now belongs to Khara, Anno’s own studio, Evangelion has since become one of the world’s highest-grossing media franchises – quite a step up from homemade short films for sci-fi conventions.

Other Osaka stars

Though Tokyo is undoubtably where a lot of the magic happens, people from all around Japan work on manga and anime. As you can see, a number of pioneers have a close connection with Osaka, but besides these, others have had great success too. Later shojo writers include Watase Yuu, the creator of fantasy series Fushigi Yugi, Lovely Complex author Nakahara Aya, and Ohkawa Nanase, leader of the manga collective CLAMP, which produced Cardcaptor Sakura, Chobits and other popular works in a variety of genres. Major shonen series have also been written by artists such as Konomi Takeshi, who created The Prince of Tennis, and Yudetamago, the duo behind wrestling manga Kinnikuman. All of these people were born in Osaka Prefecture.

Finally, Osaka University of Arts graduates include many big names in manga and anime apart from the Gainax founders. Among them are Shirow Masamune, creator of Ghost in the Shell (Kokaku Kidotai), Azuma Kiyohiko, known for comedies Azumanga Daioh and Yotsuba&!, and Minami Masahiko, producer and co-founder of anime studio Bones. Another is Shimamoto Kazuhiko, a prolific manga artist who wrote Aoi Honoo, a fictionalised account of his time at the university, featuring several other famous students as characters. The manga was made into a live-action TV series, in which Gainax founder Okada Toshio even has a cameo – as Tezuka Osamu.

Now that we’ve covered Osaka’s links to manga and anime history, please look out for Part 2, where I will talk about how some of these creators – and others – have portrayed Osaka in manga and anime, and recommend places for fans to check out!